Researchers from University of Galway have revealed the extent to which language plays a part on how migrants integrate in rural Ireland.

The study explores the experiences of people living across 11 counties in Ireland and placed a particular focus on language, both English and Irish, and its impact on migrants’ experience of employment, access to services, and community involvement.

The research forms part of the Taighde Éireann-Research Ireland-funded project Rural Villages, Migration and Intercultural Communication (VICO), led by Dr. Andrea Ciribuco from the School of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at University of Galway.

Dr. Ciribuco said: “Migrant integration in rural areas is a crucial issue for the future of Ireland and Europe, yet most migration research focuses on urban settings. Ireland also has one of the highest rates in Europe of migration into rural areas. This study and event provide a vital platform to explore the unique opportunities and challenges of rural migration.

“The high level of migrants moving to rural Ireland comes with specific challenges linked to infrastructure and migrant integration; but also with opportunities in terms of cultural and economic vitality. Too often, public discourse weighs heavily on the challenges.”

The report was launched at a public event at University of Galway on Tuesday, featuring discussions with local organisations and special guest Zak Moradi, Kurdish-Irish hurler and author of “Life Begins in Leitrim.”

The findings and recommendations are based on comprehensive fieldwork, including interviews and focus groups, conducted between March 2023 and June 2024 with 165 migrants of 31 nationalities who are living in 11 counties (Galway, Mayo, Waterford, Kerry, Cork, Kilkenny, Wexford, Clare, Tipperary, Carlow, and Limerick).

This came at a crucial time, with the relocation of more than 100,000 Ukrainian citizens to Ireland after Russia launched its war in 2022.

Ukrainians make up a consistent part of the cohort, and the study outlines many of the challenges that they encountered over two years of life in Ireland, as well as documenting the efforts made by several communities to involve them in social life.

The study underscores the complex adaptability of rural areas for migrants, shaped by factors like socio-economic opportunities and the degree of individual choice.

Key findings

English classes have a crucial role in facilitating social inclusion, building connections among migrants and with local communities

In order to retain this dimension, stakeholders prefer to host classes in-person, resorting to online only for particularly isolated communities

Mothers with small children reported having a hard time accessing classes and training due to childcare responsibilities, even when educational opportunities were available. Migrants who are eager to work point to a lack of more advanced language education which can become a barrier to satisfactory employment.

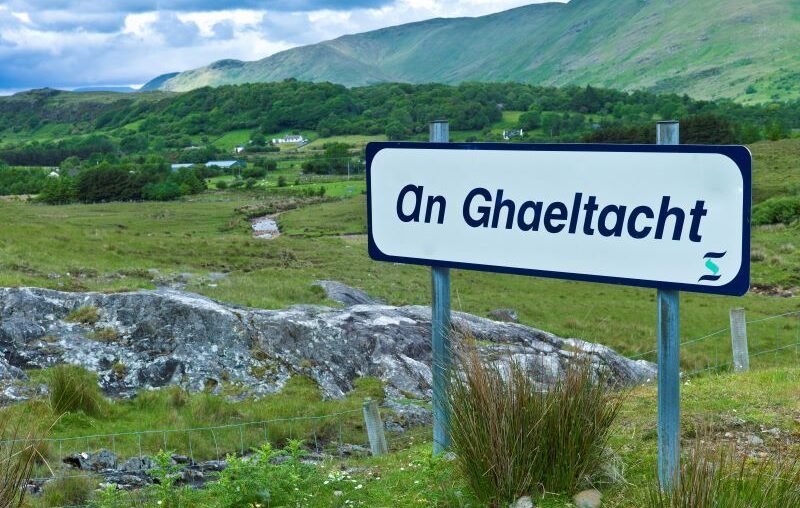

In certain regions, particularly the Gaeltacht, the Irish language can become a factor of integration. Migrants saw Irish as an important part of the local culture and heritage, and are interested in the language, especially when their children are learning it in school. But few have the time or opportunity to learn it.

Rural migration can offer positive experiences for newcomers, especially when communities actively foster cultural engagement.

Challenges – such as access to services, limited infrastructure – especially public transport, and a lack of translation and interpreting services remain significant barriers.

Family, more specifically children, is one of the determinants of adaptation to rural areas, as parents often reported being happy in the location when their children were happy.

Nearly all participants mentioned they never had negative reactions from locals when speaking their native language within a rural community. Many felt safe and more included in rural areas

Limited employment opportunities in rural settings were cited as a barrier towards living in the location for the long term but learning English was seen as a gateway to a job and, subsequently, to inclusion in Ireland

The research team also noted that migrants who had chosen to live in a specific rural setting often reported being happy there; while when the choice was made for them – as was often the case with Ukrainians – the reactions were more varied.

However, the study also found that some participants who had not initially chosen the rural location also reported feelings of well-being when they had the opportunity to feel included, for example with community initiatives.

The researchers offered recommendations based on the research:

Establish consultation processes to facilitate communication between migrants and residents, allowing both groups to express needs, concerns, and shared goals to support community integration.

Increase access to English language classes and introduce Irish language programmes, tailored to meet diverse needs, including professional development and caregiving responsibilities.

Use digital tools to supplement language education, which can help overcome barriers in rural areas by offering blended in-person and online options.

Allocate resources to train interpreters and educate communities on the risks of relying on informal or non-professional translation.

Encourage sharing successful strategies between different communities to encourage migrant inclusion in public life through innovative local initiatives.

Encourage initiatives that involve parents through schools and youth centres, recognising that children play a key role in fostering belonging and enhancing family language skills.