The connections between the world of national security and commercial companies still has surprises.

December 1976 – Vandenberg Air Force Base, U.S. military space port on the coast of California

As a Titan IIID rocket blasted off, it carried a spacecraft on top that would change everything about how intelligence from space was gathered. Heading to space was the first digital photo reconnaissance satellite. A revolution in spying from space had just begun.

For the previous 16 years three generations of U.S. photo reconnaissance satellites (257 in total) took pictures of the Soviet Union on film, then sent the film back to earth on reentry vehicles that were recovered in mid-air. After the film was developed, intelligence analysts examined it trying to find and understand the Soviet Union’s latest missiles, aircraft, and ships. By the mid-1970s these photo reconnaissance satellites could see objects as small as a few inches from space. By then, the latest U.S. film-based reconnaissance satellite – Hexagon – was the size of a school bus and had six of these reentry vehicles that could send its film back to earth. Though state of the art for its time, the setup had a drawback: Pictures they returned might be days, weeks or even months old. That meant in a crisis – e.g. the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 or the Arab-Israeli war in 1973 – photo reconnaissance satellites could not provide timely warnings and indications, revealing what an adversary was up to right now. The holy grail for overhead imaging from space was to send the pictures to intelligence analysts on the ground in near real time.

For the previous 16 years three generations of U.S. photo reconnaissance satellites (257 in total) took pictures of the Soviet Union on film, then sent the film back to earth on reentry vehicles that were recovered in mid-air. After the film was developed, intelligence analysts examined it trying to find and understand the Soviet Union’s latest missiles, aircraft, and ships. By the mid-1970s these photo reconnaissance satellites could see objects as small as a few inches from space. By then, the latest U.S. film-based reconnaissance satellite – Hexagon – was the size of a school bus and had six of these reentry vehicles that could send its film back to earth. Though state of the art for its time, the setup had a drawback: Pictures they returned might be days, weeks or even months old. That meant in a crisis – e.g. the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 or the Arab-Israeli war in 1973 – photo reconnaissance satellites could not provide timely warnings and indications, revealing what an adversary was up to right now. The holy grail for overhead imaging from space was to send the pictures to intelligence analysts on the ground in near real time.

And now, finally after a decade of work by the CIA’s Science and Technology Division, the first digital photo reconnaissance satellite – the KH-11, code-named KENNEN – which could do all that, was heading to orbit. For the first time pictures from space were going to head back to the ground via bits, showing images in near real time.

The KH-11/ KENNEN project was not a better version of existing film satellites, it was an example of disruptive innovation. Today, we take for granted that billions of cell phones have digital cameras, but in the 1970s getting a computer chip to “see” was science fiction. To do so required a series of technology innovations in digital imaging sensors, and the CIA funded years of sensor research at multiple research centers and companies. That allowed them to build the KH-11 sensor (first with a silicon diode array, and then the using first linear CCD arrays), which turned the images seen by the satellites’ powerful telescope into bits.

Getting those bits to the ground no longer required reentry vehicles carrying film, but it did require the launch of a network of relay satellites (code named QUASAR (aka SDS, Satellite Data System). While the KH-11 was taking pictures over the Soviet Union, the images were passed as bits from satellite to satellite at the speed of light, then downlinked to a ground station in the U.S. New ground stations were built to handle a large, fast stream of digital data. And the photo analysts required new equipment.

More importantly, like most projects that disrupt the status quo, it required a technical visionary who understood how the pieces would create a radically new system, and a champion with immense credibility in imaging and national security who could save the project each time the incumbents tried to kill it — even convincing the President of the United States to reverse its cancelation.

More detail in a bit. But let’s fast forward, four months later, to a seemingly unrelated story…

April 1977 – Needham, MA, Polaroid Annual Meeting

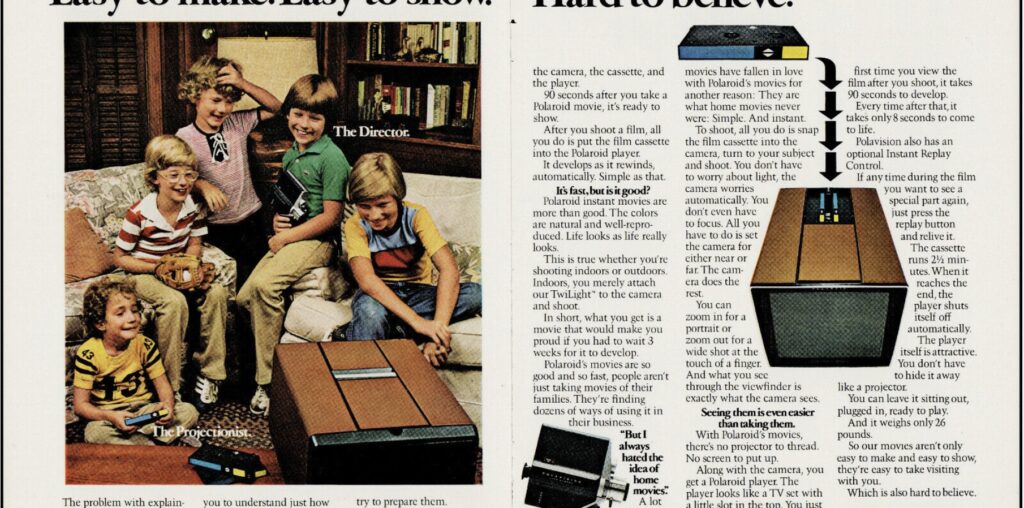

Edwin Land, the 67-year-old founder/CEO/chairman and director of research of Polaroid, the company that had been shipping instant cameras for 30 years, stood on stage and launched his own holy grail – and his last hurrah – an instant film-based home-movie camera called Polavision. At the time, you sent your home movie film out to get developed and you’d be able to view it in days or a week. Land was demoing an instant movie. You filmed a movie and 90 seconds later you could see it. It was a technical tour de force – remember this was pre-digital, so the ability to instantly develop and show a movie seemed like magic. Much like the KH-11/KEENAN it also was a complete system – camera, instant film, and player. It truly was the pinnacle of analog engineering.

But Polavision was a commercial disaster. Potential customers found it uncompelling and its $3,500 price (in today’s dollars) daunting. You could only record up to 2½ minutes of film. And believe it or not, with Polavision you couldn’t record sound with the movies. The 8mm film couldn’t be played back on existing 8mm projectors and could only be viewed on a special player with a 12” projection screen. There was no way to edit the film. It was a closed system. Worse, two years earlier Sony had introduced the first Betamax VCR and JVC had just introduced VHS recorders that could hold hours of video that could be edited. The video recorders looked like a better bet on the future. Polaroid discontinued Polavision two years later in 1979.

But Polavision was a commercial disaster. Potential customers found it uncompelling and its $3,500 price (in today’s dollars) daunting. You could only record up to 2½ minutes of film. And believe it or not, with Polavision you couldn’t record sound with the movies. The 8mm film couldn’t be played back on existing 8mm projectors and could only be viewed on a special player with a 12” projection screen. There was no way to edit the film. It was a closed system. Worse, two years earlier Sony had introduced the first Betamax VCR and JVC had just introduced VHS recorders that could hold hours of video that could be edited. The video recorders looked like a better bet on the future. Polaroid discontinued Polavision two years later in 1979.

For decades Land’s unerring instincts for instant products delighted customers. However, Polavision was the second misstep for Land. In 1972 at Land’s insistence, Polaroid had prematurely announced the SX-70 camera – another technical tour de force – before it could scale manufacturing. In 1975 the board helped Land “decide” to step down as president and chief operating officer to let other execs handle manufacturing and scale.

But the biggest threat to Polaroid came in 1976, a year before the Polavision announcement, when Kodak entered Polaroid’s instant camera and film business with competitive products.

After the Polavision debacle, Land was sidelined by the board, which no longer had faith in his technical and market vision. Land gave up the title of chairman in 1980. He resigned his board seat in 1982, and in 1985, bitter he had been forced out of the company he founded, he sold all his remaining stock, cutting all ties with the company.

Steve Jobs considered Land one of his first heroes, calling him “a national treasure.” (Take a look at part of a 1970 talk by Land eerily describing something that sounds like an iPhone.)

Meanwhile, inside Polaroid Labs, work had begun on two new technologies Land had sponsored: inkjet printing and something called “filmless electronic photography.” Neither project got out the door because the new management was concerned about cannibalizing Polaroid’s film business. Instead they doubled down on selling and refining instant film. Polaroid’s first digital camera wouldn’t hit the market till 1996, by which time the battle had been lost.

What on earth do these two stories have to do with each other?

It turns out that the person who had consulted on every one of the film-based photo reconnaissance satellites – Corona, Gambit, and Hexagon – was also the U.S. government’s most esteemed expert on imaging and spy satellites. He was the same person who championed replacing the film-based photo satellites with digital imaging. And was the visionary who pushed the CIA forward on KH-11/KEENAN. By 1977, this person knew more about the application of digital imaging then anyone on the planet.

Who was that?

It was Edwin Land, the Founder/Chairman of Polaroid – the same guy that introduced the film-based Polavision.

More in the next installment here.

Read all the Secret History posts here

Read all the Secret History posts here

Filed under: Corporate/Gov’t Innovation, National Security, Secret History of Silicon Valley |