Back in 2012, when I tried to source and read a book from every country in the world, Kuwait was one of the trickier entries on my list. There were very few traditionally published titles available in English translation. I ended up reading a self-published novel by the hit blogger Danderma, which proved an education in Arabish (Arabic words written informally in the Latin alphabet, usually on computers or mobile phones that do not support Arabic script) and the craze for frozen yoghurt sweeping the country at the time. Indeed, Danderma was very helpful to me and shared some fascinating insights into the challenges facing writers in Kuwait, some of which I related in my first book, Reading the World.

Knowing that there had to be many other interesting Kuwaiti writers whose work hadn’t yet made it into the world’s most published language, I resolved to revisit the country’s stories. Twelve years later, I’m back, thanks to a tip-off from translator Sawad Hussain, who responded to my call for books published pre-2020 that deserved a second look, as part of my year of reading nothing new.

Hussain’s translation of Saud Alsanousi’s Mama Hissa’s Mice follows the (mis)fortunes of Katkout, Fahd and Sadiq, three friends growing up in Surra, central Kuwait, during the late-twentieth and early-twenty-first century. Coming from different sects and ethnic backgrounds, the young men share little but their fury and frustration at the divisions that compound the destruction wrought in the wake of the Iraqi invasion. In an attempt to overcome this, they form a group, Fuada’s Kids, which aims to bind Kuwaitis together by appealing to their nostalgia, but in so doing risks costing them everything.

Disorientation is at the heart of this novel. The narrative, like the central characters’ world, is fractured and splintered, reflecting the feeling that ‘it’s as if an enormous fist has plowed into Kuwait, leaving it in ruins’. The present-day, adult reality is intercut with flashbacks and with chapters from an autobiographical novel, some of the of which have been removed to placate the government censors.

Indeed, censorship is another key theme. Growing up, the boys learn that questions can be dangerous. Seemingly innocuous issues such as how someone pronounces a word or the spelling of certain names can crack open rifts and even invite physical violence. Small wonder, then, that self-censorship and sanitization flow through many of the conversations, because, as Fahd’s grandmother Mama Hissa is fond of observing, ‘all cowards stay safe.’

For English-language readers, there is an extra level of challenge. The unease and self-questioning that the story prompts with its challenging structure and courting of the unsayable is compounded with cultural disorientation. It is often unclear how certain statements should be read. We can’t know the significance of certain jokes – or whether some phrases are meant as jokes at all. The childhood memory of the boys pretending to be Palestinians throwing stones at Jews, for example. Is this said ironically, or bitterly? Would this be shocking in this society or unquestioned? And how ought we to respond?

There are also a large number of unfamiliar cultural terms in the text. Hussain does an elegant job of elucidating key elements but refuses to patronise or pamper readers by over-explaining. The terms are left Roman rather than italicised – a reminder that it is we, rather than the world of the story, who are foreign. (For more on the politics of italicisation, check out Daniel José Older’s YouTube video ‘Why We Don’t Italicize Spanish’ below.)

But there are also moments of powerful connection. From Alsanousi’s skilful marshalling of the child’s-eye view to reveal the strangeness of behaviours adults take for granted, to his intense, visceral presentation of moments of fear and suffering, and from the way he builds nostalgia to his layering of action so that we grow to remember events as the central characters’ do, this novel reaches out and grasps us.

It also showed me my own world through new eyes. A Londoner born and bred, I had long been in the habit of looking askance at the overseas investors who own empty properties in many of the capital’s most desirable postcodes. Reading Mama Hissa’s Mice made me consider the question from another angle: when you live with the threat of invasion and societal collapse, ‘foreign houses are assets for when something happens’. Wouldn’t many of us make similar choices if we had experienced such things?

This was a difficult read. But as a result it was also surprising one. An enriching one. A challenging one. It required me to sit with not-knowing in the same way that Shalash the Iraqi did – accepting my limitations and recognising that this is not a story that can or should centre my knowledge or perspective as so many of the books produced by the anglophone publishing industry do. I’m very glad to have had the chance to experience it.

Mama Hissa’s Mice by Saud Alsanousi, translated from the Arabic by Sawad Hussain (Amazon Crossing, 2019)

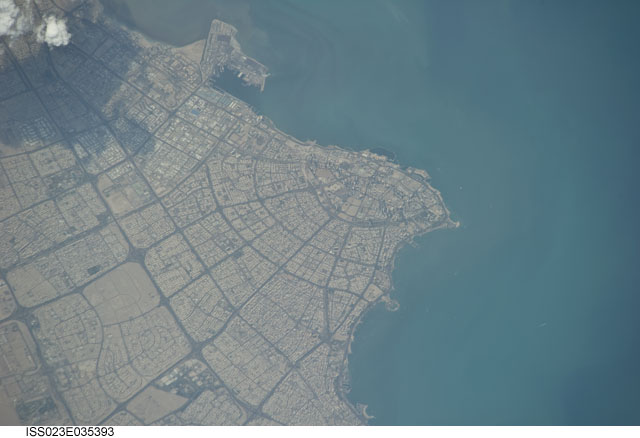

Picture: NASA Astronauts, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons