Located between the two popular Tokyo districts of Asakusa and Ueno, the buzzing thoroughfare of Kappabashi-dori is very much the place to go for kitchenware in the city, lined with stores selling everything from high end pots and pans to the plastic food samples widely seen throughout Japan. Among the multitude of stores selling knives of all shapes and sizes, the flagship Musashi Hamono Kappabashi branch stands out with its attractive design, friendly atmosphere and – intriguingly – an upstairs sake tasting bar.

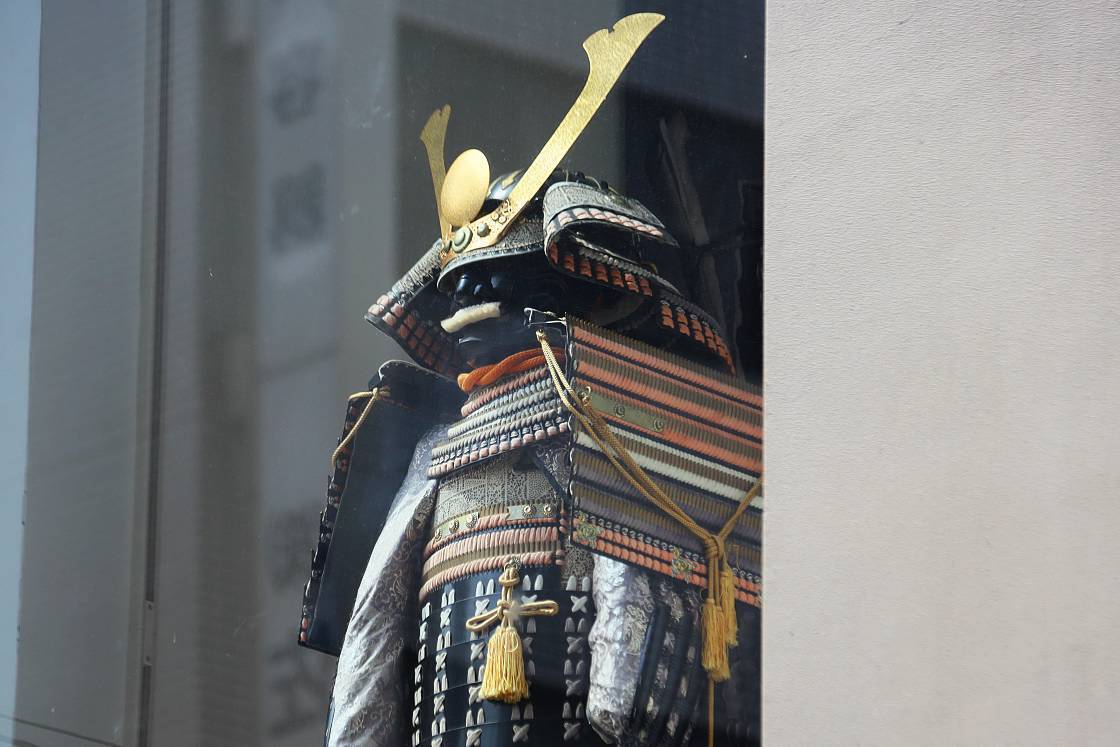

Taking its name from the legendary samurai Miyamoto Musashi, Musashi Hamono was founded in 2020 as an online only enterprise, expanding to brick and mortar stores throughout the country as recently as 2022.

Known for its inventive and very modern approach, the brand allows potential customers to learn about Japanese knives and even get individually tailored advice via a livechat feature before even arriving in the country. In-store, those same customers can meet staff who are typically young, clean cut, impressively knowledgeable and passionate about their subject – many are also from other countries, allowing them to show their expertise in a range of languages from German to Chinese.

Taking a look inside the main store, I found a huge range of knives, from traditional to modern and with an impressive variety of styles, fittings and decoration. The company, I discovered, works in partnership with an expanding circle of artisans, like Asamura Takao – an expert in blade-carving, or chokin, with over 50 years of experience in the field. Asamura has been known to dedicate months and even an entire year to meticulously refining an individual knife.

Like much of its cultural heritage, Japan’s tradition of knife making developed over many hundreds of years, influenced by the course of history as well as the parallel evolution of its fine cuisine. When Japan was finally unified in 1603 after centuries of civil war, master sword makers faced a steep decline in demand for their services. Many adapted to the times by making kitchen knives instead – bringing with them the same advanced skills, philosophy and purpose that they had to creating instruments of war.

Peacetime, meanwhile, spurred the growth of big cities like Edo – today Tokyo – where an entirely new social class of artists, merchants and skilled craftsmen was already on the rise. These chonin, or townsfolk, were ambitious, interested in profit and had a taste for the finer things in life – creating the beginnings of a consumer culture.

It was during this period that some of the classic types of Japanese knife began to appear, such as the deba (a heavy, pointed fish knife that is at once a cleaver and boning knife) and the yanagiba (a long, slender knife able to slice boneless filets of fish in a single, smooth stroke). Others like the gyuto – a Western-style knife for cutting meat – emerged later as foreign influence weakened the cultural taboo surrounding eating meat.

Musashi excels at celebrating the heritage of their knives while presenting them with a modern design and sensibility – a prime example being the Tsushima series. Of the 14,125 islands in the Japanese archipelago, Tsushima is one of the very worst impacted by plastic sea pollution. In response, Musashi worked to create a line of knives with handles fashioned from exactly this recycled plastic – each one is an entirely unique mix of colors, and feels comfortable in the hand.

While many of the knives on display understandably come with significant price tags, I found Musashi to be refreshingly down to earth in their presentation – customers are free to handle and even try out any item that catches their eye, and staff took the time to demonstrate how to sharpen and maintain knives for decades of practical use.

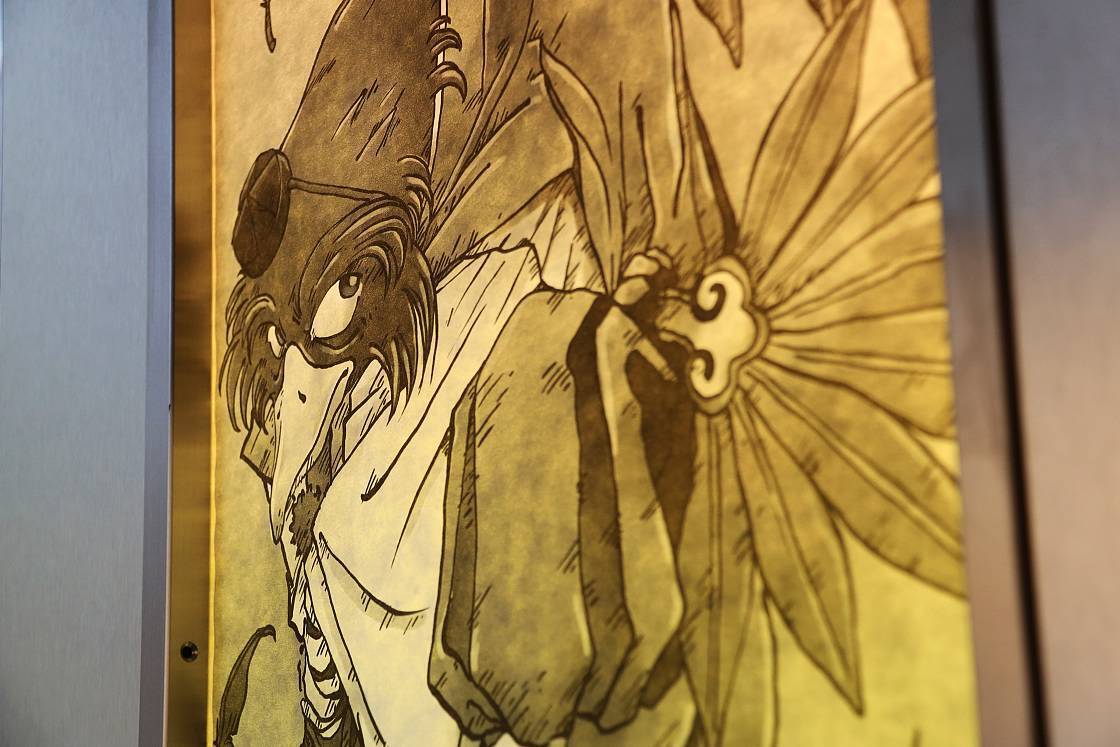

After a good look at the knives downstairs, I made my way up to the cozy 2nd floor sake tasting area, decorated with some artisanal pottery pieces and images of ghosts and other mythical beings called Yokai – staff explained that this is a reference to the rich thread of folklore running through the neighborhood’s history.

Visitors can order individually or from a choice of three tasting menus: “Emotions”, which I chose, is beginner friendly and easy on the palette, “Samurai” offers a little more complexity, while the in between option of “Japanese ghosts” is a nice range from sweet to dry.

Emotionstasting set

Leaving the main store behind, I took a short stroll along the same street to Musashi’s Minami Kappabashi branch. Despite a similarly stylish look – my eyes were immediately drawn to a large antique kimono cabinet restored with orange plastic accents – the atmosphere here felt less touristy and a little more down to earth. Here I met Hansen, a staff member from Norway, who moved to Tokyo to live with his Japanese wife.

As Hansen explained, gWorking in Kappabashi is really nice. A lot of the customers who come here are kitchen professionals or enthusiasts and that makes it extra enjoyable to interact with them. Cooking has been my hobby for 13 or so years now and it is a lot of fun to share that passion and geek out with our customers.h

Listening to Hansen, I was especially impressed by the way Musashi’s staff seemed to fit right into Kappabashi’s tightly-knit working community: “Although there are 25 dedicated knife shops on the street, there is more of an atmosphere of cooperation than competition. Staff from other stores often come to visit; we share knife knowledge, Japanese staff help us with our Japanese, and we give them pointers on their English. All in all, a wonderful street to be working in.”

Taking a left turn off of Kappabashi Street, I took a ten-minute stroll along the busy Shin Nakamise Shopping Street to my final stop at Musashi’s Asakusa Branch, located just a few blocks south of Sensojifs famous Hanzomon Gate. With an inviting, open design to capitalize on the area’s heavy foot traffic, the store has an exciting buzz to it and I hear several languages spoken in the course of my short visit.

Here, I found myself chatting to Johannes, originally from Germany, who came to Japan back in 2017 – a change he described as the biggest and best of his life – and was ultimately drawn to work at Musashi: “Since I was interested in knives, knifemaking and cooking for a long time now, learning so much about Japanese knives was really interesting.”

Much like Hansen, Johannes said he relished the buzzing atmosphere of the Kappabashi area, but even more so the chance to be part of a truly international team: “We hire staff from all over the world, so working together with people from different backgrounds and countries has given me the opportunity to learn about other cultures as well – working together becomes a really fun and worthwhile experience.”

Before saying my goodbyes, I couldnft resist asking if he owned any Musashi knives himself. “Sadly not yet! But I do have a specific one that I can’t get out of my mind – a gyuto, made from 99-layer Damascus silver steel #3. It’s an amazing piece of craftsmanship, and every cut feels like butter.”

There’s a particular feeling one gets when a topic you might have touched on before suddenly takes on an unexpected depth and excitement – somehow, something is so much more relatable and fascinating, and you’re just going to have to get to the bottom of it. My visit to Musashi Hamono was a lot like this.

From its impressive selection of beautifully handcrafted knives to its thoroughly inspiring team members and their ability to bring the topic of knifemaking to life, Musashi Hamono is the ideal place for visitors looking to bring home their own piece of Japan’s culinary tradition.