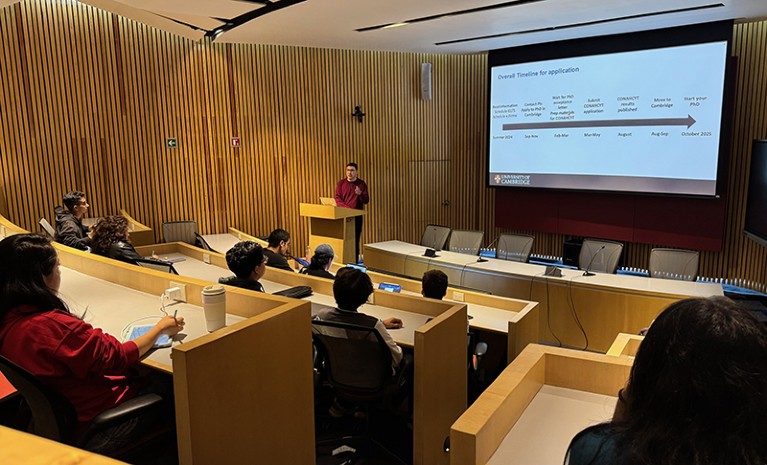

David Posner (at lectern) introduces his plan to bring students from Mexico’s Vasco de Quiroga University to Cambridge, UK, for a research stay.Credit: Pedro Andres Garcia Escamilla

Born in the United States to a Mexican mum and a UK–US dad, I grew up in Mexico but relocated back to the United States in 2012, aged 16 years old, to finish my education. After completing a biochemistry degree at Siena College in Loudonville, New York, in 2019, I moved to the University of Cambridge, UK, to pursue a PhD in neuroimmunology — the study of how the immune and nervous systems interface.

However, during annual visits to see family and friends in Mexico, I had become increasingly aware of the stark disparities in higher education, particularly in terms of access to resources and opportunities for young researchers.

Although I routinely conducted costly RNA-sequencing experiments and used super-high-resolution microscopes in Cambridge, my peers in Mexico relied on free online sequencing databases, rather than generating their own data, and worked with outdated tools of limited function. My UK and US colleagues were aware of the relative lack of support for scientists in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), but I felt that no one was rushing to find a solution.

To help to address that, in the first year of my PhD, I launched a series of small-scale initiatives to support students in Mexico. Here are a few practical steps, based on my experiences, that anyone in a well-resourced laboratory can implement today to democratize access to scientific resources and training worldwide.

Share specialized expertise

I began by offering to deliver undergraduate lectures on immunology to students at the Vasco de Quiroga University (UVAQ) School of Medicine in my home town of Morelia, Mexico. The lectures, delivered on Zoom late in the UK night to accommodate the time difference, covered content beyond typical textbook material, including recent research that the students might not have encountered. These introductory sessions soon expanded into research-centric seminars covering innovative RNA-sequencing assays, interpretation of flow-cytometry plots and concepts of experimental design.

David Posner gives a talk about applying for PhDs at the University of Cambridge through a scholarship funded by Mexico’s National Council of Science and Technology (CONAHCyT).Credit: Daniel Guzman Toledo

Researchers can easily replicate this approach by offering virtual seminars or workshops in their area of expertise — whether broad or niche — to institutions that might otherwise not be able to mount such events easily. Platforms such as LinkedIn or X can work well for connecting with labs that might benefit from guest lectures. Exposure to cutting-edge techniques is common in well-resourced institutions but often inaccessible to under-resourced labs, making virtual masterclasses invaluable.

Host visiting researchers

I realized that providing hands-on research experience was key to empowering future scientists. So, I organized research placements for Mexican undergraduates, inspired by a competitive summer programme I’d completed at the University of California, San Francisco, and at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, before my move to the United Kingdom. In 2021 and 2022, with the support of my supervisor, Menna Clatworthy, and my senior tutor, Andrew Spencer, four students were selected to participate in a ten-week summer programme, with two placed at the University of Cambridge and another two at Mexico’s top research university, the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in Querétaro.

Splitting costs between home and host institutions can make these financially challenging programmes more feasible. I initially approached UVAQ by highlighting the benefits to students, and demonstrating how having ties to an institution abroad would be attractive to prospective students. Basically, I convinced the university to see this as a win–win deal. Senior university officials agreed to cover the cost of flights and a stipend, and the Cambridge colleges I approached agreed to provide housing for the students.

By facilitating short-term stays, labs can provide invaluable training for researchers from under-resourced institutions. The experience not only enriches the education of participants but also builds a pipeline to connect PhD and postdoctoral candidates with prospective host institutions. In Mexico, this experience guarantees better clinical and research placements for the students we select, giving their career a springboard to a physician-scientist track. It also broadens their perspective beyond working in a local hospital, offering the possibility of becoming scientists at Mexico’s top hospitals and research institutes.

Support entrance to postgraduate programmes

Attracting students from lower-resource countries can be challenging for complex reasons such as funding, language barriers and the isolation experienced by many academics based at institutions in LMICs. When I was applying to PhD programmes, I heard about an obscure source of funding: a scholarship, the CONAHCyT-Cambridge Scholarship for Mexican citizens, that became my lifeline. Sadly, this fund, which involves a partnership with Mexico’s National Council of Science and Technology (CONAHCyT), remains underutilized owing to a lack of awareness and understanding of the application process. I was determined to get others to make use of the scholarship I credit with enabling my move to Cambridge.

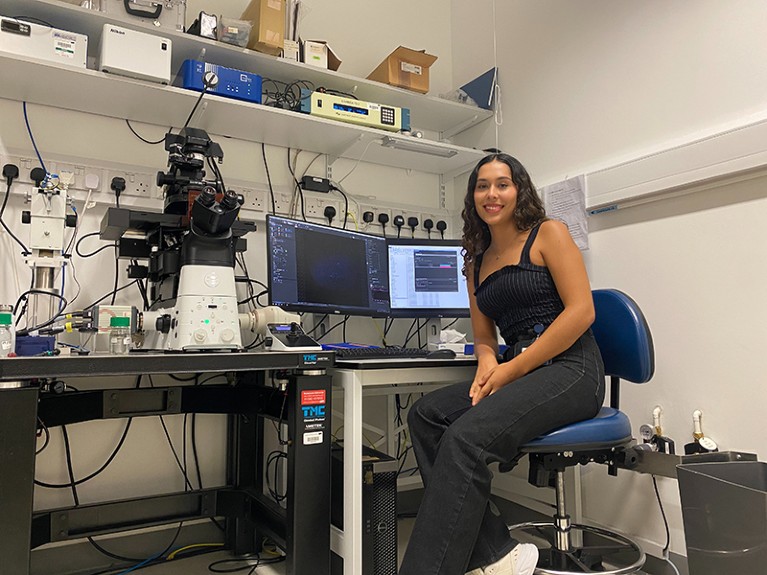

Tzanda Camarena in her in the lab at the MRC LMB in Cambridge.Credit: Tzanda Lopez Camarena

I pitched an idea to my department in Cambridge: that raising awareness of the scholarship and driving students to take advantage of it would bring substantial funding to the faculty and attract students from under-represented backgrounds to Cambridge, boosting our equity, diversity and inclusion efforts. This garnered financial support for my efforts to raise awareness. In August 2024, I began travelling around Mexico, using my network on X to find interested universities where I could promote these opportunities and offer personal guidance to prospective students. I shared my own experience at several departments at UNAM and the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education, offering insights into the application process and providing tips for crafting competitive submissions.

At the same time, I reached out to Cambridge’s admissions office to offer assistance with recruitment efforts in Mexico. Admissions teams often encounter challenges related to language, culture and logistics when engaging with potential applicants from LMICs. Students with backgrounds similar to those of people in the target audience, such as myself, can have a crucial role in surmounting these barriers, significantly enhancing outreach and communication strategies. Whether by helping to translate discussions during virtual meetings with prospective students, promoting the host institution in their home country or participating in online Q&A sessions, their contributions can make a meaningful difference. Initiatives such as this help to increase the visibility of opportunities and can contribute to diversifying applicant pools at leading institutions.

Frankly, this work took considerable effort by my part. At times, I felt as if it was only me trying to keep these initiatives afloat by following up on e-mails requesting funding, preparing teaching plans and marking work. It helped me to find balance in other aspects of my PhD, including experiments, formal dinners in college, conference travel and teaching. Fundamentally, I used my passion for helping others to get me through the tough moments. Seeing students fall in love with research and realize their own potential made it all worth it.