This brings us back to the heart of the Condon commentary.

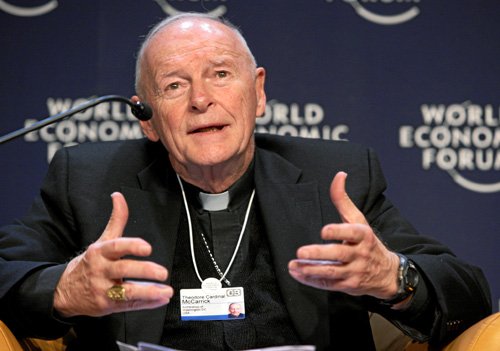

I came into Catholic media in 2018, pretty much the week the McCarrick scandal broke. … I spent my first year in journalism wondering how, how something as big as McCarrick could play out in plain sight for so long and go unchallenged. And, as a canon lawyer with a few years of practice in abuse cases under my belt, I wondered how the basic legal mechanisms of reporting and justice could have failed so spectacularly for so long.

The answers to both those questions became apparent to me in relatively short order. The legal processes failed because McCarrick was — for many, many years — too big to fail in the ecclesiastical world.

He was too highly placed, too well-connected, too well-financed to be held to account by ordinary means. And he was so influential as a tribal figurehead, patron, friend, and source to so many people in the Catholic world that he could count on any rumor about his crimes being dismissed as just that: rumor.

The key word — “source.”

Digging into the Vatican report about McCarrick’s career, Condon notes crucial words from one of the most respected voices in journalism about all things Roman Catholic.

Here is some of the key material, as quoted in another source, The National Catholic Reporter:

… Allen indicated that the fact that McCarrick was a “newsmaker” was a reason for his not pursuing the story: “If you go after somebody like this, especially a Cardinal, you lose him, and probably any of his friends, as a source.”

He goes on to explain in the report: “The problem for journalists — all journalists — is that we are invested in treating our sources as important. To sell news, which is what we do, we have to convince people that those we are covering really matter. So, we build them up in some ways as being titans of the earth, even though we know, at another level, it may involve a lot of smoke and mirrors … So, when you have a guy who is not just smoke and mirrors, who is smart and effective and willing to be pretty open with the press, you just don’t want to believe that they would be doing something so stupid as sleeping in the same bed with seminarians.”

Condon notes another Allen quote, stating that if journalists tried to probe all the accusations aimed at bishops — especially when dealing with a cardinal — “you lose him, and probably any of his friends, as a source.” A reporter who chased all the “salacious” rumors, he added, would “be out of business in a heartbeat.”

In many cases, reporters (I know several) heard about the lawsuits and reports linked to McCarrick, but could not get sources to go on the record, thus putting their names in print. Clearly, many feared McCarrick’s clout and connections. In a few cases, major investigations nearly reached newsstands, but editors never flipped switches to put them into print.

Journalists may fear losing sources. In the niche-news world, editors may also fear angering readers.

In an age in which online advertising dollars are scarce or nonexistent, check-writing subscribers, and donors, are the lifeblood of independent newsrooms. Angry readers can start wars in social media or, even worse, they can cancel their subscriptions.

Today, niche-news publications have become major players — covering important news that mainstream journalists may consider too “inside baseball.” In many cases, important religion stories “break” in smaller, independent publications and these headlines catch the attention of journalism elites in New York or Washington, D.C.

Thus, it matters that The Pillar’s coverage of the Príncipi scandal has caused some fallout. Condon writes:

“Our paying subscribers are down — we’ve lost revenue, noticeably. Reporting the things we know matter, giving them the attention they deserve and refusing to let them go or to be fobbed off with answers designed to distract might indeed be bad business.

Maybe it’s a terminal mistake to make. I don’t know.

But here’s what I do know: I don’t care.

The rising power of angry readers and donors played a crucial role in my 2023 feature story for the journal Religion & Liberty, which ran with this headline: “The Evolving Religion of Journalism.” I drew some crucial material from journalism historian Marvin Olasky, best known for decades of work as editor of World magazine.

… In the brave new world of digital journalism, news organizations will need to be honest about the impact of their readers on the news product. After all, subscribers are now just as powerful as advertisers, and that clout is growing year after year.

“That equation has become obvious,” says Olasky. However, elite journalists have not been willing to say, “We are creating our news to fit a specific audience.” …

In this environment an ancient question has become relevant: What is truth?

Enjoy the podcast and, please, share it with others. And please keep supporting the scribes and editors who produce the alternative news and commentary publications that are so important in the Internet age.