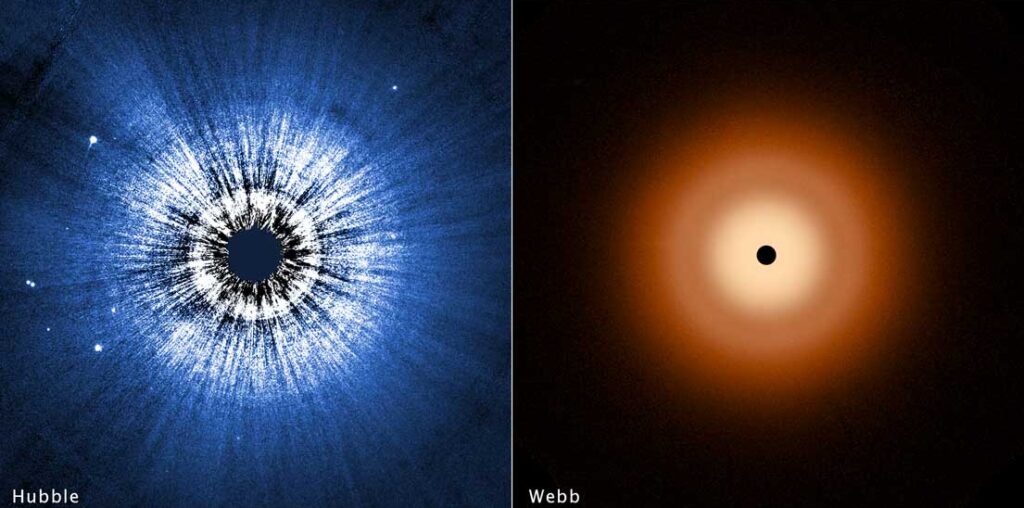

Astronomers have used the Hubble and James Webb space telescopes to gain an unprecedentedly clear view of the disk of gas and dust surrounding the star Vega. There’s no sign of large planets orbiting within it, forcing astronomers to reconsider the range of possible disk architectures and how common planetary systems like the solar system are.

NASA / ESA / CSA / STScI / S. Wolff, K. Su, A. Gáspár (University of Arizona)

Vega, the stellar standout of the constellation Lyra, the Lyre, has long intrigued astronomers. It is one of the brightest stars in the sky, and the glow of all other is measured against it. To say that the circumstellar disk around Vega is vast would be an understatement — it spans about 100 billion miles. That’s more than 1,000 times Earth’s distance from the Sun.

A team of astronomers at the University of Arizona, Tucson, used Hubble to peer at the outer, cooler part of the disk, finding small, smoke-sized particles glinting in Vega’s light. Another team from the same institution then used Webb to look into the hotter, inner part of the disk, finding bigger particles the size of sand grains. The papers outlining their findings are published on the arXivpreprint server.

“The fact that we’re seeing dust particle sizes sorted out can help us understand the underlying dynamics in circumstellar disks,” says Hubble observation lead Schuyler Wolff. This dichotomy is likely due to light from Vega preferentially pushing lighter particles farther out than heavier ones.

“It’s a mysterious system because it’s unlike other circumstellar disks we’ve looked at,” says team member Andras Gáspár. “The Vega disk is smooth, ridiculously smooth.” The only deviation is a subtle gap in the disk located about twice as far from Vega as Neptune circles the Sun.

Some other stars’ disks exhibit distinct gaps that are thought to have been cleared out by the gravity of giant planets, so the absence of such objects could explain the extreme smoothness of Vega’s disk. The combined Hubble and Webb data rule out any planet bigger than Neptune on a large orbit. In the early history of our own solar system, the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn disrupted a lot of the dust around the Sun, preventing it from spreading and separating in the way that it has in Vega’s disk.

NASA / ESA / CSA / A. Pagan (STScI) / A. Gáspár (University of Arizona)

“We’re seeing in detail how much variety there is among circumstellar disks,” says Kate Su, team lead for the Webb observations. “There’s still a lot of unknowns in the planet-formation process, and I think these new observations of Vega are going to help constrain models.”

Tim Pearce (University of Warwick, UK), who was not involved in the research, agrees. “These new images must be telling us something about how planets form and evolve,” he says. “It’s easy to assume that all stars have planetary systems similar to our solar system, but this isn’t necessarily true.”

According to René Oudmaijer (Royal Observatory of Belgium), who also was not involved in these studies, “it is becoming more established that more massive stars are less likely to be accompanied by planets than lower mass stars such as our Sun.” (Vega is at least twice as massive as our own star.)

Another possibility is that Vega does have planets, but they are smaller than these new observations were sensitive to. “Some of these higher mass stars — if they make planets — may not produce them at high enough planetary masses to sculpt the disks,” says Lynne Hillenbrand (Caltech), who also was not involved in this new work.

Stellarium / Rick Fienberg

Finding sub-Neptune-size planets around Vega — if any exist — will not be easy, because we view the star and disk pole on. Currently, the only planets that astronomers can find by direct imaging of nearby stars are bright “super-Jupiters.” The presence of smaller planets can be deduced indirectly by measuring their host stars’ line-of-sight velocity “wobbles” or their periodic dimmings as planets transit their faces, but these powerful planet-hunting tools work only if the orbits are oriented more edge on from our perspective.

The Vega system may not even be that odd. “It may be that this system is unusually well-studied, and unusually close (and thus well-resolved), rather than intrinsically unusual,” Hillenbrand says.

Vega has transfixed astronomers for centuries, and the new Hubble and Webb observations only serve to deepen its allure.