The Sankei Shimbun is publishing a series on significant figures and themes of the Showa era (1926-89). One highlighted individual is boxing professional Guts Ishimatsu, born as Yuji Suzuki in 1949.

In this installment of the series, Ishimatsu recalls the excitement and challenges of growing up in postwar Japan and his road to becoming a professional boxer.

Excerpts follow.

The Poorest Family in the Village

I’m part of what they call the “baby boomer generation.” Growing up, everyone was out for themselves, climbing over one another just to get ahead. It was that kind of time, you know?

I lived that way too, just trying to survive, day by day. As long as I had food on the table, that was enough. I ended up becoming the World Boxing Council (WBC) lightweight champion and defended the title five times [in 1974 and ’75]. But honestly, I just focused on what was right in front of me, thinking, “Tomorrow’s another day.”

I was born in Kiyosu Village in Tochigi Prefecture. Later, it became Awano Town. Now it is part of Kanuma City. We lived in a little house on the edge of the village and were the poorest family around. I was the second son out of four kids. No TV, of course — and even a radio was something only the rich folks had.

Could Only Pinch Hit on Junior High Baseball Team

In junior high school, I joined the baseball team. There was an incredible pitcher named Yutaka Saotome at a neighboring junior high, who would later go pro (1973-84, starting with the Hanshin Tigers). When I got my chance as a pinch hitter, I was a bit slow on the swing but still managed to knock a single to right field off Saotome.

For a while, I even thought about becoming a pro baseball player myself. But baseball … that’s really a sport for rich kids. Kids like me couldn’t afford gloves or bats. Since I didn’t have a glove, pinch-hitting was all I got to do.

Around that time, Fighting Harada was in the spotlight, and I really looked up to him. I decided to become a pro boxer too, so right after junior high when I was 15, I moved to Tokyo.

When I left home, my mom handed me a ¥1,000 bill with Prince Shotoku‘s face on it. I had been working part-time during junior high, handing over my earnings to help the family. She saved that money for me without spending it. I still keep that ¥1,000 bill close to my heart.

Becoming ‘Guts Ishimatsu’

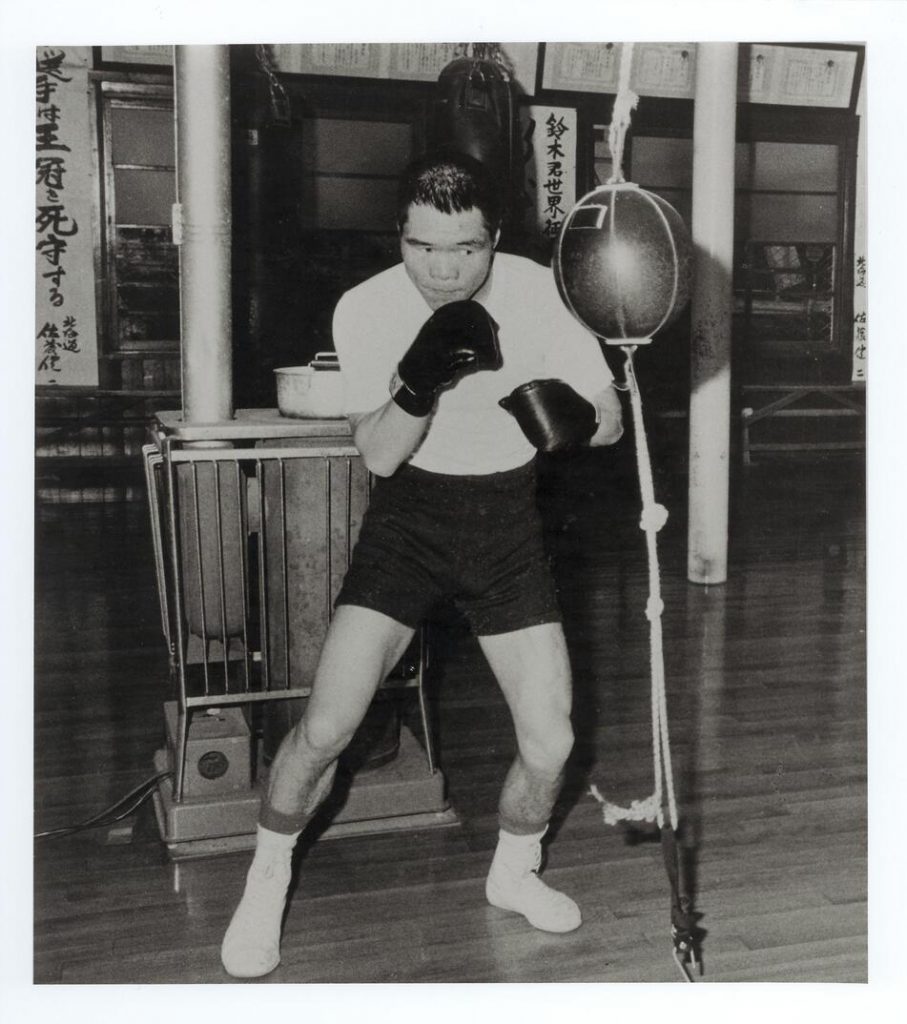

I started out working at a screw factory in Gotanda, Tokyo. However, I quit and joined the Yonekura Gym in Otsuka [in Tokyo]. My fight pay was just ¥5,000 ($33), and after gym fees and expenses, I only took home ¥3,300 ($21.50). Since fights weren’t that frequent, side jobs became my real work. In one, I scooped flavors at an ice cream shop. For another, I worked at a bento shop. I was always hungry and would sneak a bite here and there.

The gym gave me the ring name “Guts Ishimatsu,” meaning “a boxer with guts.”

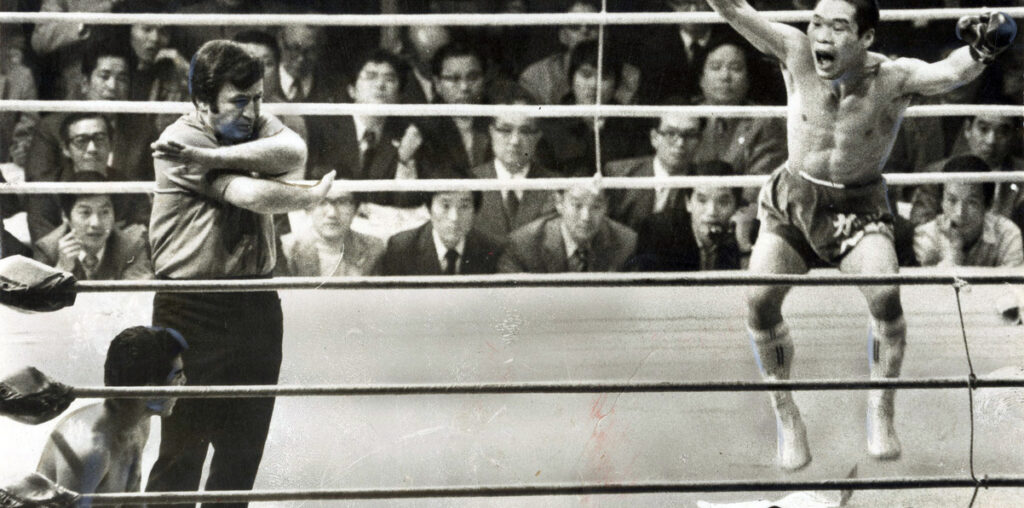

I’ll never forget April 11, 1974 (a title fight against WBC lightweight champion Rodolfo Gonzalez of Mexico). On my third attempt, I finally became the world champion. I let out a shout, “I’m the champion!” A photo of that moment made it to the newspaper the next day, and that’s how the term “guts pose” came about.

Even now, April 11 is celebrated as “Guts Pose Day.” With my prize money, I fixed up my parents’ old house, which had been leaking every time it rained.

Boxing Disappears from Prime-Time Television

After retiring, I became an actor and had the chance to appear in all kinds of popular national dramas. There was Oshin, Kita no kuni kara (From the North) and Hanekonma.

In Oshin, I played the role of Ken Nakazawa. The show had an average viewership of over 50% and peaked at more than 60%. Do we even have shows like that anymore, ones the whole family sits down to watch together?

These days, in the Reiwa era, there’s apparently a strong guy named Naoya Inoue, the unified super bantamweight world champion. But I can’t watch his fights. They’re only available on streaming platforms. Back in my day, boxing was on prime-time TV, but now we’re in an era where people have to pay to watch if they’re interested.

But it’s not about right or wrong. The times and environments we grew up in are just different, and it is what it is.

RELATED:

(Read the column in Japanese.)

Interview by: Tomonori Gonome