November fireballs? Each year from roughly late October through mid-November, a dazzling Taurid meteor just might take you by surprise in the night. If you get very lucky.

Normally the broad, weak, South and North Taurid meteor showers sputter along with maybe 5 or 10 ordinary little meteors visible per hour even under ideal moonless conditions. What makes the Taurids potentially exciting is that their small numbers are known for a high proportion of bright fireballs — occasionally, an extremely bright one that makes the news. If you see an especially bright, relatively slow meteor these nights, check whether its line of flight, if traced backward far enough across the sky, would intersect more or less the Pleiades side of Taurus.

FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 8

■ First-quarter Moon (exact at 12:55 a.m. tonight EST). The Moon shines this evening inside the dim, boat-shaped pattern of Capricornus. Cover the Moon with your finger to see the 3rd- and 4th-magnitude Capricornus stars better.

A couple of fists upper left of the Moon is Saturn. Two fists below Saturn is Fomalhaut, similar in brightness.

■ For telescope users this evening, the shadow of Jupiter’s moon Io crosses the planet’s face from 8:51 to 11:03 p.m. EST, followed by Io itself from 9:34 to 11:45 p.m. EST. Convert these times to your own time zone.

Meanwhile, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot should cross the planet’s central meridian around 10:19 p.m. EST. The spot should be visible with about the same degree of difficulty for an hour before and after then in a good 4-inch telescope if the seeing is sharp and steady.

And look for any signs of bluish festoons in the north edge of Jupiter’s Equatorial Zone. See “Observing Jupiter’s ‘Blue Holes’ ” in the November Sky & Telescope, page 52.

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 9

■ The season tilts winterward. Around 8 or 9 p.m. now, depending on where you are, zero-magnitude Capella, star of winter, climbs exactly as high in the northeast as zero-magnitude Vega, the Summer Star, has sunk in the west-northwest. How accurately can you time this event?

■ Happy 90th birthday, Carl Sagan (November 9, 1934 – December 20, 1996). If only.

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 10

■ The waxing gibbous Moon shines quite near Saturn this evening for the Americas. In fact, its dark limb will occult Saturn for southern Florida, Central America, the Caribbean, and parts of South America. Map and timetables. For instance, seen from Miami, Saturn will slowly disappear at 9:26 p.m. EST, then will slowly reappear from behind the Moon’s bright limb at 10:05 p.m. EST.

MONDAY, NOVEMBER 11

■ Vega is the brightest star high in the west-northwest these November evenings. Its little constellation Lyra extends to its left, pointing as always to Altair, currently the brightest star in the west-southwest.

Three of Lyra’s stars near Vega are interesting doubles. Barely above Vega is 4th-magnitude Epsilon Lyrae, the Double-Double. Epsilon forms one corner of a roughly equilateral triangle with Vega and Zeta Lyrae. The triangle is less than 2° on a side, hardly the width of your thumb at arm’s length.

Binoculars easily resolve Epsilon. And a 4-inch telescope at 100× or more should, during good seeing, resolve each of Epsilon’s wide components into a tight pair.

Zeta is also a double star for binoculars. It’s much closer and tougher, but is plainly resolved in a telescope.

And Delta Lyrae, upper left of Zeta by a similar distance, is a much wider and easier binocular pair. Its stars are reddish orange and blue.

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 12

■ A more famous double star from Vega: Continue somewhat farther left from Lyra’s pattern, and there, about a fist and a half from Vega, is 3rd-magnitude Albireo, the beak of Cygnus. This is one of the finest and most colorful double stars for small telescopes: Pale gold and bluish, magnitudes 3.2 and 4.7, separation 35 arcseconds.

Farther on in roughly the same direction you come to 3rd-magnitude Tarazed and, just past it, 1st-magnitude Altair.

WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 13

■ When Saturn and Fomalhaut are”southing” (crossing the meridian due south, which they do around 7 or 8 p.m. this week), the Pointers of the Big Dipper stand upright low due north, straight below Polaris.

And, the first stars of Orion are soon to rise above the east horizon (for skywatchers in the world’s mid-northern latitudes). Starting with the rise of Betelgeuse, it takes Orion’s main figure about an hour to completely clear the horizon.

THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14

■ As the stars come out, the Great Square of Pegasus is still balancing on its corner high in the southeast. It’s about three fists upper right of the Moon. But within an hour or so, it turns around to lie level like a box high in the south.

A sky landmark to remember: The western (right-hand) side of the Great Square points far down almost to 1st-magnitude Fomalhaut. The eastern side of the Square points down toward Beta Ceti — not as directly, and not as far.

FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 15

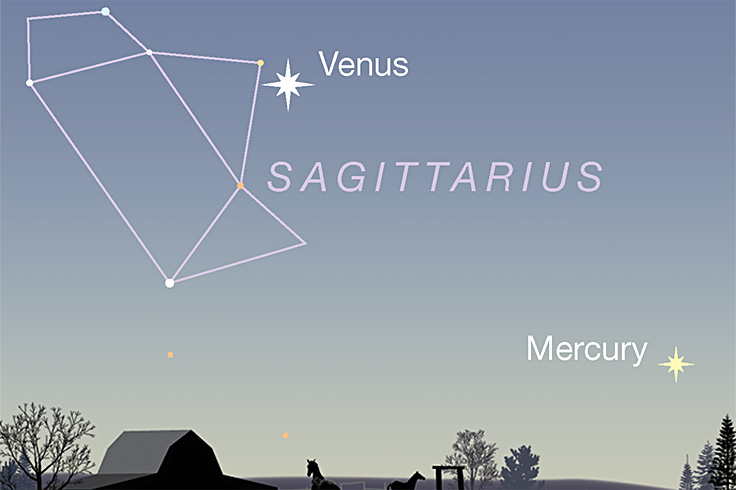

■ As twilight fades on any evening this week, see if you can catch Mercury nearly two fists lower right of Venus in the southwest, as shown below.

■ Full Moon (exact at 4:29 p.m. EST). How soon after the Sun sets in the west-southwest can you see the Moon rising in the east-northeast?

Once night arrives, look for the delicate Pleiades a few degrees to the Moon’s lower left (for North America). Cover the Moon with your finger to block its dazzling glare.

Much farther lower left of the Moon, once night is well under way, gleam orange Aldebaran and brighter Jupiter.

Much later in the night tonight the Moon occults some of the Pleiades. However, the full Moon’s brilliance and nearly complete lack of a dark limb will make these events for telescopes only. And use high power to get most of the Moon out of the eyepiece.

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 16

■ The just-past-full Moon shines above Jupiter after dark. Watch the Moon move closer to Jupiter all through the night.

■ The Leonid meteor shower should peak late tonight, but the brilliant moonlight will interfere. And the Leonids have been weak to begin with for the last decade or more.

■ Uranus is at opposition.

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 17

■ By about 8 or 9 p.m. Orion is clearing the eastern horizon (depending on how far east or west you live in your time zone). High above Orion shine Jupiter and, to Jupiter’s right or upper right, orange Aldebaran. Above Aldebaran are Pleiades, the size of your fingertip at arm’s length. Far left of Aldebaran and the Pleiades shines bright Capella.

Down below Orion, Sirius rises around 10 or 11 p.m. No matter where they are, Sirius always follows two hours behind Orion. Or equivalently, one month behind Orion.

This Week’s Planet Roundup

Mercury (magnitude –0.3) is still pretty deep in the afterglow of sunset this week and next, even though these are the best two weeks of its current evening apparition. Try for it with binoculars or a wide-field telescope very low in the southwest about 30 minutes after sunset. Look 18° to the lower right of Venus.

Venus (magnitude –4.1) gleams in the southwest in evening twilight, higher every week now. It doesn’t set until about 45 minutes after the end of twilight.

Mars (magnitude –0.1 in Cancer east of Gemini) rises in the east-northeast around 9 or 10 p.m. — at almost the precise point where Jupiter did 3¼ hours earlier. Mars shows best in a telescope when very high toward the south in the hour or two before the start of dawn. It’s 42° east along the ecliptic from Jupiter.

Mars has enlarged to about 10.2 arcseconds in apparent diameter. It’s on its way to a relatively distant opposition in January, when it will reach an apparent diameter of 14.5 arcseconds.

Jupiter (magnitude –2.7, still near the horntips of Taurus) rises in the east-northeast just after the end of twilight. It’s highest toward the south after midnight. Jupiter is now a nice 47 arcseconds wide in a telescope, essentially as large as the 48-arcsecond width it will attain for the weeks around its December 7th opposition.

Saturn, magnitude +0.9 in Aquarius, glows highest in the south in early evening. Don’t confuse it with Fomalhaut twinkling two fists below it.

Uranus (magnitude 5.6, at the Taurus-Aries border) is at opposition this week. It’s well up in the east after dark about 7° from the Pleiades. You’ll need a good finder chart to tell it from its surrounding faint stars; charts are in the November Sky & Telescope, page 49.

Neptune (tougher at magnitude 7.8, under the Circlet of Pisces) is high after nightfall, 15° east of Saturn. Again you’ll need a proper finder chart.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world’s mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions and graphics that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America.

Eastern Standard Time (EST) is Universal Time minus 5 hours. UT is also known as UTC, GMT, or Z time.

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They’re the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For a more detailed constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you’ll need a much more detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas (in either the original or Jumbo Edition). Both show all 30,000 stars to magnitude 7.6, as well as 1,500 deep-sky targets — star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies — to search out among them.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many, as well as more deep-sky objects. It’s currently out of print, but maybe you can find one used. The next up, once you know your way around well, are the even larger Interstellarum atlas (stars to magnitude 9.5) or Uranometria 2000.0 (stars to mag 9.75) and correspondingly more deep-sky objects. And read How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope. It applies just as much to charts on your phone or tablet as to charts on paper.

You’ll also want a good deep-sky guidebook. A beloved old classic is the three-volume Burnham’s Celestial Handbook. An impressive more modern one is the big Night Sky Observer’s Guide set (2+ volumes) by Kepple and Sanner. The pinnacle for total astro-geeks is the Annals of the Deep Sky series, currently at 11 volumes as it works its way forward through the constellations alphabetically. So far it’s up to H.

Can computerized telescopes replace charts? Not for beginners I don’t think, and not for scopes on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically. Unless, that is, you prefer spending your time getting finicky technology to work rather than learning how to explore the sky. As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer’s Guide, “A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand and a curious mind.” Without these, “the sky never becomes a friendly place.”

If you do get a computerized scope, make sure that its drives can be disengaged so you can swing it around and point it readily by hand when you want to, rather than only slowly by the electric motors (which eat batteries).

However, finding faint telescopic objects the old-fashioned way with charts isn’t simple either. Learn the essential tricks at How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope.

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty’s monthly

podcast tour of the naked-eye heavens above. It’s free.

“The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It’s not that there’s something new in our way of thinking, it’s that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before.”

— Carl Sagan, 1996

“Facts are stubborn things.”

— John Adams, 1770