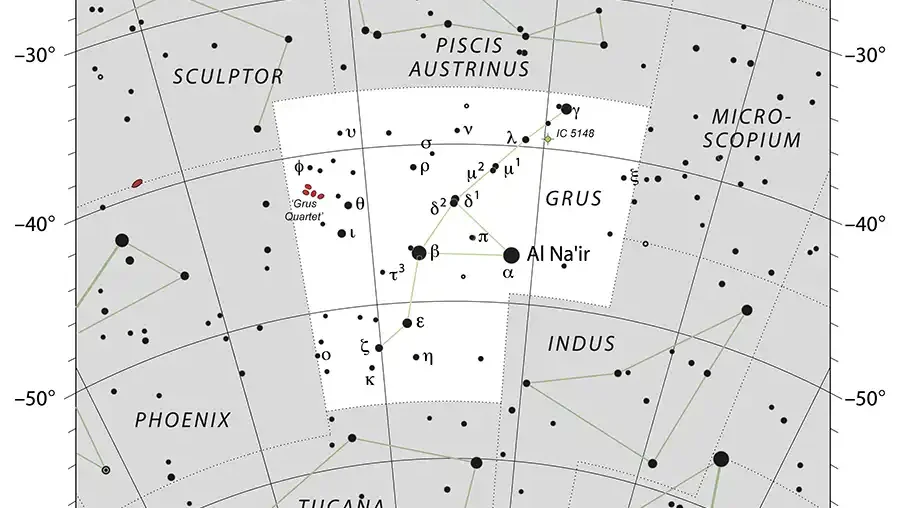

The constellation Grus, which means Crane in Latin (of the bird variety), is often overlooked and I’m not really sure why. Maybe it’s simply due to other surrounding constellations being loaded with deep-sky targets, such as Sculptor with its gaggle of galaxies. Grus’s relative obscurity is unfortunate, as it contains a variety of pleasing sights to suit all tastes.

Learn more about Grus in Annals of the Deep Sky, Volume 11, a comprehensive reference that guides amateur and semipro astronomers into every mind-boggling corner of the observational universe. Published by Sky & Telescope.

ETH Zurich

Like many constellations, Grus has gone through some changes over the years. Many of its brightest stars originally belonged to the bordering constellation Piscis Austrinus. It was Petrus Plancius who, in the late 16th century, carved out the separate avian grouping we now know as Grus. Later on, some other celestial cartographers briefly tested out other bird monikers, such as the heron and the flamingo, but they failed to catch on.

At first glance, Grus is dominated by its two brightest stars. Alnair, or Alpha (α) Gruis is a, bluish-white, magnitude-1.7 B-type main-sequence star about 520 times more luminous than the Sun. Residing only 100 light-years from Earth, it’s fairly close in space terms. The other star, red giant Beta (β) Gruis, about 177 light-years distant, is a semiregular variable star that ranges in magnitude from around 1.9 to 2.3 over a period of 37 days. And it really is a giant — it’s thought to be 150 times wider than the Sun and more than 3,000 times more luminous!

IAU / Sky & Telescope / Roger Sinnott & Rick Fienberg

Grus has some very attractive wide double stars; that is, ones that are far enough apart to be obvious to the unaided eye. Delta1 Gruis (δ1) — itself a tight binary system — and the red giant Delta2 Gruis (δ2), for instance, are separated by an easy 16 arcseconds, while Mu1 Gruis (μ1), another binary system, and Mu2 Gruis (μ2) are about 19 arcseconds apart.

Grus has some nice close doubles for small telescopes, too. One is Dunlop (Δ) 246, which might not be identified as such on your planetarium software — try the alternate designation SAO 247738. (Its coordinates are 23h 08 m, –50° 33′, just in case). Start at Epsilon (ε) Gruis and head 2° east and slightly north until you reach a pale-yellow, magnitude-5.6 star, then go a further 1° east and slightly north, and here you’ll find Δ 246. It’s an attractive pair with magnitudes of 6.2 and 7.0, currently separated by about 9″. The two have similar proper motions, so astronomers have suggested they might actually be gravitationally connected and a true binary pair.

Another easy-to-find double is Δ 248 or SAO 247838 (23h 20.8m, –50° 18′). To spot this one, keep going east-northeast from Δ 246 for another 2° 10′, and there it is — an attractive duo comprised of magnitude 6.2 and 6.6 stars, separated by around 17″.

Fernando de Menezes / S&T Online Photo Gallery

When it comes to deep-sky objects, Grus is well-known for having a foursome of interacting galaxies known as the Grus Quartet — NGC 7552, 7590, 7599, and 7582. A 4½-inch aperture is sufficient to start to reveal each of the four under good skies, with three of them (7582/90/99) close enough to each other to fit within a single, low-power field. To locate the Quartet, sweep 1° 55′ northeast from Theta (θ) Gruis and you’ll first come across NGC 7552, followed 27″ later in the same direction by 7582. A further 10″ will bring the NGC 7590 and 7599 pair into view.

NGC 7552 (mag. 10.6) is a splendid sight through a 6-inch scope. It’s orientated almost straight east-west and has an elongated appearance. An 8-inch-or-larger telescope will help show hints of a halo extending toward the north and south.

Next in line is the middle galaxy, NGC 7582 (mag. 10.5), which to my eyes appears larger than NGC 7599. It is orientated northwest-southeast and is more obviously spiral, given the angle at which we view it.

The easternmost member of the Quartet is NGC 7599 (mag. 12), which displays a definite elongated shape through the eyepiece, while the nearby NGC 7590 (mag. 11.3) is also extended but is smaller and a bit rounder. Both are arranged in a NE-SW orientation.

Team Chameleon / Franz Hofmann & Wolfgang Paech / S&T Online Photo Gallery

Challenging the Quartet for the title of best object in Grus is the planetary nebula IC 5148, also known as the Spare Tire Nebula. Discovered by the Australian amateur astronomer Walter Gale in 1894, it’s a small, round, condensed object of magnitude 16.5 spanning only about 2 by 2 arcminutes. It’s found by starting at Lambda (λ) Gruis and heading 1° 17′ almost due west. A 6-inch telescope reveals its round form, while larger apertures bring its tire or donut nature to life, especially with the use of an O III or UHC filter.

Incidentally, does the surname Gale ring a bell? If you’ve been following activities on Mars, it would, because Gale Crater, named after the same amateur, is where NASA’s Curiosity rover has been exploring since August 2012. In addition to a fascination with the deep sky, Gale was a keen observer of Mars, too.

That brings us to the end of this flying tour of Grus. I hope you’ve enjoyed the scenery, and I trust that you’ll come back to visit this area of the sky again in the very near future, because there’s plenty more to see.