Located just a few minutes’ walk northeast of Tokyo Station, the district of Nihonbashi is a buzzing commercial hub known for its imposing architecture, countless shops and restaurants, and as the home of some of the city’s most important institutions, from the headquarters of the Bank of Japan to the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

If the vast metropolis of Tokyo could be said to have a heart, it would arguably be here – an area not only at the forefront of many major developments in business and consumer culture, but the literal center of it’s national highway system from which all distances are measured.

Among the many distinguished shops and businesses lining the district’s busy streets, one of the most iconic and best loved is Nihombashi Mitsukoshi Main Store – Japan’s first modern department store, with a history spanning over three centuries.

For our latest video project, we set out to discover exactly what makes Mitsukoshi so special, before exploring some of the area’s other highlights.

Nihonbashi’s emergence as an important urban center can be traced back to 1603 and the early days of the Tokugawa Shogunate. As one of several areas surrounding what was then Edo Castle, it was naturally a place where elite samurai bureaucrats could brush up against the city’s ever expanding lower classes of merchants and craftsmen.

Adding to the flow of money and goods was Nihonbashi’s position at the meeting point of all five of Japan’s major historic highways, making it by far the most important crossroads in the country.

In 1603 – the same year that he adopted the title of Shogun – the great warlord and unifier of Japan, Tokugawa Ieyasu, ordered the construction of the landmark that still gives the district its name: the Nihonbashi Bridge.

While visitors can see a full-sized replica of the original wooden structure at the Edo-Tokyo Museum in Sumida, the bridge itself was updated to its current form – built from stone over a steel frame – in 1911. Reflecting the changing face of Japan’s civic infrastructure, its architect was both a senior member of the Finance Ministry and a graduate of America’s Cornell University.

While the view from the bridge is quite literally overshadowed by an overhead expressway – scheduled for removal in 2040 – visitors can still enjoy a series of elegant bronze statues including four shishi or lion guardians standing watch at the corners, while ornate lamp posts decorated with mythological kirin stand atop the two central pillars.

Much like its surrounding area, Nihombashi Mitsukoshi can trace its origins back to the Edo Period. Originally named Echigoya, the business first opened in 1683 as a kimono fabric store and money exchange. Even from the beginning, the company took an innovative approach, introducing labeled pricing and the option to cut fabrics to order. While the current department store opened in 1914 it was rebuilt just a few years later following the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923.

Passing between the iconic lion statues at the main entrance, visitors are met with an elegant interior with marble pillars, art deco patterns and modern details by designers including Kuma Kengo.

In pride of place at the center of a high, glass covered atrium is a brilliantly colorful and elaborate statue of Tennyo – the Buddhist deity of sincerity. Created by sculptor Sato Gengen, the work was painstakingly cut from a single 500-year-old cypress tree and took ten years to complete.

Two other interesting details can also be found within the five story atrium – overlooking the staircase behind the grand sculpture is a 90-year-old pipe organ, kept in full working order and still used for occasional performances, while if you look closely at the pink marble cladding the walls and pillars, you may be able to pick out ammonites and other fossils embedded inside.

After taking in the scale and artful decoration, I made my way down into the basement food level, or depachika. Often the busiest and most exciting part of any Japanese department store, it’s a space packed with everything from refined snacks to high end ingredients and all manner of beautifully pre-prepared dishes.

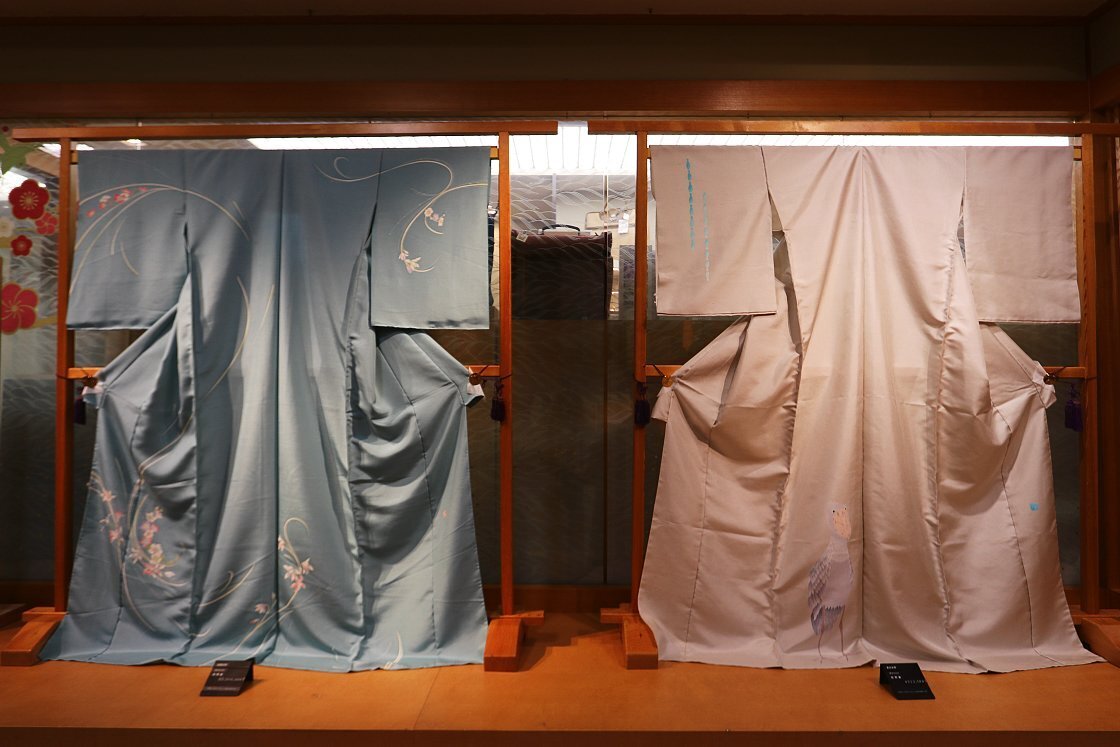

Given its origins as a seller of kimono fabric, it’s no surprise that Mitsukoshi’s kimono department (4F) is second to none. Here, visitors can find expertly crafted kimono fabrics and accessories, in a wide range of colors and designs.

While some may find the price of a complete kimono an eye-wateringly expensive prospect, this can still be the perfect place to pick up a refined yet affordable souvenir, from beautifully patterned fans to furoshiki – a square of patterned fabric used to wrap gifts and other small items.

For those looking for traditional handcrafts or the kind of lifestyle goods you might find in a stylish modern Japanese home, the place to find them is the living department (5F). Exploring this part of the store was a definite highlight, as I thoroughly enjoyed combing through the huge selection of expertly crafted items.

Mitsukoshi isnft just great for shopping – visitors can also check out a spacious gallery on the sixth floor with a wide range of paintings, sculptures, objects, tea sets and tableware. This comes with some pretty serious prestige for the artists that exhibit there, and of course – if you have the budget, you can even buy the pieces!

My final stop at Mitsukoshi was at the store’s attractive rooftop garden, a peaceful space complete with a shaded seating area, leafy strolling paths, an outdoor bonsai store and – most fascinating of all – a miniature shrine, flanked by two guardian fox statues.

In fact, this is a branch of Mimeguri Shrine, located some 5 kilometers northeast on the bank of the Sumida River, to which Mitsukoshi can boast a centuries long connection.

Leaving Nihonbashi Mitsukoshi behind, it was time to set out and discover some of the other highlights in the area, starting with a visit to the famous artisanal paper store, Ozu Washi.

Paper has a long history in Japan, having been introduced from China by way of the Korean peninsula in around 610. It is said to have been the near-legendary prince Shotoku Taishi himself – the same ruler who presided over the introduction of Buddhism to Japan – who first suggested the use of kojo or mulberry fibers to increase its durability, giving rise to the incredibly versatile material still widely seen today. Known for its slightly rough texture and the way it elegantly diffuses light, its uses range from calligraphy paper and business cards to lanterns and sliding doors.

Among the oldest and most distinguished traditional businesses in the Nihonbashi area, Ozu Washi first opened in 1653 and, while its original timber structure has long since been replaced, the store has never moved from its first address.

Inside, visitors can browse an impressive collection of different paper and writing materials, learn about the heritage and tradition of washi in the upstairs museum or experience making their own washi paper at one of the regular craft workshops.

Under the guidance of Takagi-san, Ozu Washi‘s public relations manager, I took my place beside a tank filled with a mix of water, dissolved plant fiber and sap in the shop’s dedicated craft space. By carefully sifting the solution through a mesh lined frame in a very specific series of scooping and tipping movements, a layer of fibers began to collect on the surface – forming a single sheet of washi paper.

After very gently removing the paper, all that remained was to stick it onto a heated plate to dry off. While my own sheet ended up a little bit lumpy in all the wrong places, it was still hugely satisfying to watch the surface of the paper form into its distinct natural texture, so pleasing to the eye and touch.

Saying my goodbyes to Takagi-san, I retraced my steps to the Nihonbashi Bridge, where the Riverboat Mizuha sightseeing boat – one of several in the area offering shared and chartered tours available to book online – was waiting to take me on a guided 75-minute cruise of the surrounding rivers and canals.

Much like the five historic highways at whose meeting point Nihonbashi originated, waterways formed a vital part of Tokyo’s feudal-era infrastructure, with a network of canals connecting Edo Castle at its center with the Sumida River and beyond. While many have since disappeared, others – many of which are former castle moats – have survived to the present. Far more than a quicker and easier means of transporting goods, this system would also help to shape the social development of the city, as markets, theaters, teahouses and even licensed pleasure quarters sprang up close to the water’s edge, and many chose to travel to them in style, by boat.

With the Meiji Period and modernization however, this kind of scenery – immortalized in countless ukiyo-e prints – rapidly gave way to a more industrial landscape, while riverboats were surpassed by trains as the method of choice for moving freight.

A final brick in the wall for Tokyo’s riverborn culture came in the leadup to the Tokyo Olympics of 1964. With Japan’s government eager to make a grand entrance onto the world stage, a scramble began to complete an ambitious program of new infrastructure, including an urban network of expressways, in just six years.

There was however one huge challenge to overcome in the form of thousands of home and business owners across the city whose properties stood to be negatively impacted. To circumvent this, planners created elevated expressways directly over rivers and canals – space that the city itself owned – trading a vast piece of its living city for a transport system of unparalleled sophistication and convenience.

As fascinating as it would be to slip back in time to marvel at what Tokyo’s rivers and canals must have been, still it was a hugely enjoyable experience to see the city from a new and surprising angle. Everywhere I looked I had the sense of pulling back the surface to reveal the bones underneath, here a section of Edo Castle’s stone wall complete with centuries old inscriptions, here the studded metal pillar of some bridge or looming expressway.

Discreetly tucked away on an unassuming back street, Kashiwaya Ningyocho is a delightfully cozy and intimate little restaurant, run by a charming husband and wife team.

Here, the speciality is a course menu of traditionally arranged small plates known as kaiseki, but where this kind of cuisine can be a bit daunting for the uninitiated, Chef Kashiwabara Yoshiyuki – formerly of Japan’s overseas consular service – is a warm and often entertaining presence.

On the night of my visit, the menu ran the full gamut from fresh sashimi to spring vegetable tempura to stewed Yamagata beef, so tender that it seemed to melt in my mouth.

With so many spectacular dishes it seems impossible to pick out particular highlights, but I couldn’t not mention the shrimp somehow sculpted into the form of an adorable little bird, or the rice with herbs and dried shrimp that was somehow unlike anything I had ever tasted before.

Any products and pricing shown reflect the time of publication.