From China’s mass internment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, to Syria’s torture and extermination of thousands of detainees, to Russia’s forcible transfer of civilians from occupied areas of Ukraine, no region of our planet is free from crimes against humanity. Nor are the perpetrators limited to state actors. Between 2014 and 2017, the militant group calling itself Islamic State committed unthinkable crimes against the Yazidis and many other communities in Iraq and beyond, including mass killing, abductions, enslavement, torture, and rape.

In the last 12 months in particular, we have witnessed the most horrific crimes in Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories, with potential crimes against humanity by both sides being investigated by the International Criminal Court (ICC), yet nothing seems capable of putting an end to the carnage in Gaza and the decades-long cycle of impunity.

From China’s mass internment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, to Syria’s torture and extermination of thousands of detainees, to Russia’s forcible transfer of civilians from occupied areas of Ukraine, no region of our planet is free from crimes against humanity. Nor are the perpetrators limited to state actors. Between 2014 and 2017, the militant group calling itself Islamic State committed unthinkable crimes against the Yazidis and many other communities in Iraq and beyond, including mass killing, abductions, enslavement, torture, and rape.

In the last 12 months in particular, we have witnessed the most horrific crimes in Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories, with potential crimes against humanity by both sides being investigated by the International Criminal Court (ICC), yet nothing seems capable of putting an end to the carnage in Gaza and the decades-long cycle of impunity.

The absence of justice for many such crimes is a shameful indictment of the international justice system. It has to do largely with the breakdown of the rules-based order and double standards in the application of international law.

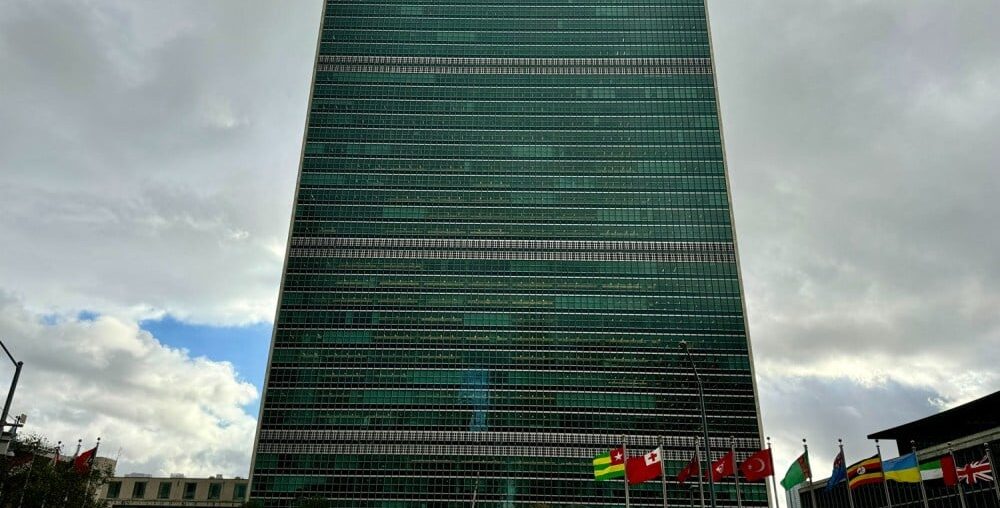

But impunity for these crimes is also because of glaring gaps in how these acts are criminalized and prosecuted. This is a problem that the project on a Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Crimes Against Humanity seeks to address. After years of discussions, this fall the United Nations General Assembly must seize the opportunity and finally open formal negotiations on adopting the treaty—lest these efforts be shelved indefinitely.

Unlike other international crimes, such as genocide and war crimes, there is currently no standalone convention for crimes against humanity.

Crimes against humanity entail certain acts committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack against a civilian population. The Rome Statute of the ICC describes them as “atrocities that deeply shock the conscience of humanity,” including murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation or forcible transfer of population, unlawful imprisonment, torture, rape and other sexual violence, persecution, enforced disappearance, apartheid, and other inhumane acts of a similar character.

In the last decade, Amnesty International has found that such crimes have been committed in at least 18 countries, including the draconian crackdown on women and girls’ rights in Afghanistan, sexual violence and unlawful killings by Eritrean forces in Ethiopia, and mass arbitrary detentions and extrajudicial executions in Venezuela.

A Crimes Against Humanity Convention would impose obligations on states not only to criminalize and punish such crimes through national legislation, but also to prevent them and to cooperate with other states in gathering and exchanging information on suspects and victims, proceeds of crime, and other evidence. This would allow the community of states to investigate and prosecute a much larger number of crimes against humanity than an international court such as the ICC could, given its jurisdictional, budgetary, and staff limitations. A case in point is the proceedings opened in several European countries against suspected perpetrators of international crimes in Syria, over which the ICC has no jurisdiction at present.

The current draft would make states obligated to either prosecute or extradite any suspects of crimes against humanity in their territories or within their reach, regardless of where the crime was committed or the nationality of the suspect or victim. This is a vital principle rooted in the belief that some crimes are so heinous, they fall under the responsibility of every state in the international community. It is for this reason that the Geneva Conventions and the U.N. Convention Against Torture include this same obligation, which has proven key to prosecute certain war crimes and torture. For instance, the Convention Against Torture provided the legal basis for the United Kingdom to arrest Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet in 1998, acting on a warrant from Spain.

The treaty could also bring much-needed improvement of international standards on gender justice, including by incorporating new gender-based crimes against humanity, such as forced marriage and forced abortion. In particular, the convention represents an important opportunity for the world to heed the calls of the trailblazing women of Afghanistan, Iran, and beyond, and recognize gender apartheid as a crime against humanity.

That said, it would be naive to consider this a panacea that will entirely eradicate these heinous crimes or the impunity around them. There are still considerable hurdles to overcome in terms of both adopting and enforcing a convention.

Regarding the former, the prognosis is generally encouraging.

As of late October, close to 90 states from all over the world—including the United States—have formally expressed support to enter negotiations. But more are still needed. The convention’s supporters will have to be unequivocal and firm in their backing, lest they be sidelined by a vocal minority including China, Russia, Syria, and Saudi Arabia, who are masking their opposition in calls for further discussions and delays.

Some states have argued that the ICC makes a convention redundant given that that court already has jurisdiction over such crimes in some cases. Such a position seems to be aimed at slowing or even blocking consensus—and rings particularly hollow when voiced by states that are not even parties to the ICC.

The Rome Statute outlaws and aims to punish crimes against humanity committed by individuals, among other crimes. But a dedicated Crimes Against Humanity Convention would move beyond this framework by adding duties of states. It would not create a new international court but provide states with a comprehensive, updated, and harmonized model for domestic legislation on crimes against humanity. It would be applied by and between states, including any not accepting the ICC’s jurisdiction.

Despite these tensions, we can draw encouragement from the consensus behind the Ljubljana-The Hague Convention that was adopted last year and has already been signed by 36 states. That landmark treaty clarifies and cements the duties of states to cooperate with each other in the investigation and prosecution of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. It introduced several groundbreaking provisions that the Crimes Against Humanity Convention can build upon, such as the general obligation for states to either extradite or prosecute suspects; and strong and survivor-centric provisions on the rights of victims and witnesses, including enforcing orders between states for reparations to victims.

The two conventions would be complementary. The Ljubljana-Hague Convention is primarily aimed at enhancing legal cooperation between states after a crime is committed, while the Crimes Against Humanity Convention would encompass the entire set of obligations related specifically to crimes against humanity, including their prevention.

Once adopted, the biggest challenge will be to ensure that this new convention avoids the pitfalls around meaningful and effective enforcement that undermine so many international treaties.

Common criticisms of the ICC—made by Amnesty International, among others—are its selective approach to investigations; its lack of prompt and tangible results; and its double standards and Western bias. Until the recent applications for arrest warrants against Russian President Vladimir Putin and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, it had focused exclusively on prosecuting a small number of offenders, all of whom were in Africa. The 2020 decision not to investigate war crimes by U.K. forces in Iraq, despite its own prosecutor finding that such crimes had been committed, was particularly inexcusable.

The new convention cannot address the absence of political will to deliver justice. But it will strengthen the hands and advocacy of all those who fight against impunity and for the universal and absolute commitment to justice for all. It will empower activists to demand investigations and prosecutions by national authorities for crimes against humanity committed in their countries, but also abroad—similarly to the criminal case brought against Venezuelan authorities in Argentine courts. This will make it a powerful tool to pursue accountability for such crimes irrespective of who committed them and where. Enabling and emboldening state authorities and independent judiciaries to better conduct their own investigations and prosecute crimes through their domestic courts—including cases that the ICC is unable or unwilling to pursue—means victims will be less reliant on the ICC to take up a case.

In short, the proposed convention would significantly improve the present system. Its benefits leave states with a clear choice. Even a cursory glance at the state of the world and the strain on the international justice system should convince governments to commit to backing the convention. After more than a decade of discussions, they must not let opposing states obfuscate and further delay the process. Now is the time.