Regarded as one of the most sacred places in Japan, Koyasan is a plateau deep in the mountains of Wakayama Prefecture, the center of the Shingon sect of Buddhism and a popular tourist destination due to its historic buildings, serene forest surroundings and in particular the chance to stay overnight at several of its temples.

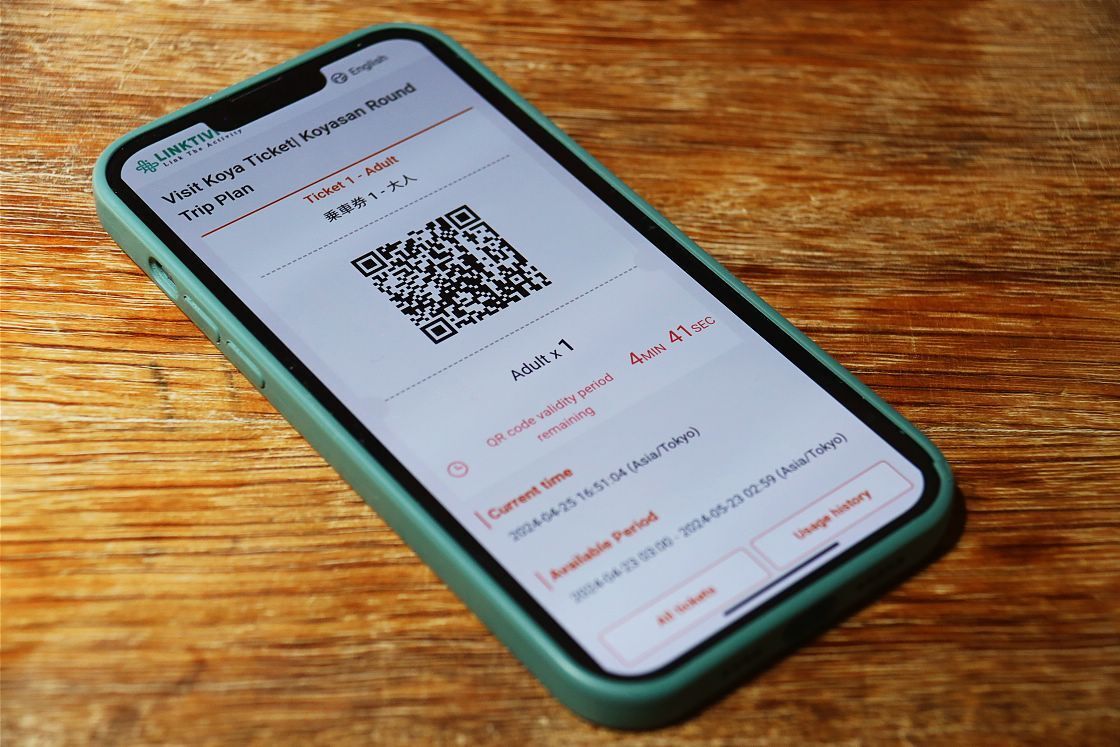

In this two day trip, we set out to introduce some of Koyasan’s main highlights on a two-day visit to the mountain, including how to get there from the nearest major city of Osaka, while trialing the new digital ticket from Nankai Electric Railway. Valid for two days, the ticket includes a round trip from Namba to Koyasan as well as free use of buses on the mountain for hassle-free sightseeing.

My journey began at Nankai Namba Station – a major transport hub in the heart of Osaka’s southern downtown area, surrounded by shops, restaurants and sightseeing spots. Having already pre-purchased the ticket online, all I had to do was scan a QR code at the ticket machine before passing through the ticket gate.

Once inside, I boarded a express train along the Nankai Koya Line in the direction of Koyasan Station – a pleasant journey of a little over 100 minutes with one change at Hashimoto – taking me out of the city and deep into the mountains of Wakayama Prefecture.

Arriving into Gokurakubashi, I changed to the Koyasan Cablecar heading up the steep mountainside approach to Koyasan Station. In just a few moments, a local bus arrived to bring me deeper into the mountain interior and along the single main road that serves as the center of town. Lining the streets, I saw ornate roofs rising above walled compounds, and a series of gates – some quite beautifully carved – offering brief glimpses of neat little gardens beyond.

The story of how this unique community came into being goes all the way back to the Heian Period and the monk Kukai (774-835). Originally from Shikoku, he learned to read the Chinese classics at an early age and traveled to Nara – then the center of Buddhist learning in Japan – to pursue his studies.

The still young monk’s rise to prominence began suddenly in 804 when he was selected to join a state-sponsored delegation to Tang China. Over the next two years, he threw himself into studying Chinese Buddhism and Sanskrit, ultimately meeting the monk Huiguo who began his initiation into the esoteric tradition – bodies of Buddhist teaching and lore that included mystical elements or that could only be taught to a select few. The same Huiguo would later describe the process of teaching his disciple as like pouring water from one vessel into another, and although they would spend just two years together before the old man’s death, Kukai left as his anointed successor and with the blessing to establish a new esoteric sect back in his home country.

Upon his return to Japan, Kukai immediately set about establishing what would become the Shingon faith, but it would take over a decade of struggle before he could begin his ultimate project – a center for the new religion, where its members could devote themselves to training in peace and seclusion. In Koyasan, he found the perfect location – set on a plateau at an elevation of about 800 meters, surrounded by inner and outer circles of mountains with eight peaks each forming the shape of a lotus. With permission from the Emperor Saga, he was finally able to begin settling the mountain in 819.

The monastic community grew rapidly, reaching the peak of its size and power in the 15th century with over 1,800 individual temples. Over the next century however, large monasteries would find themselves in the crosshairs of land-hungry warlords, with the decline only continuing with the solidification of samurai rule. Today there are just 119 temples on the mountain, but it remains the center of the Shingon faith – one of the most popular and influential sects of Buddhism in Japan.

After a 20 minute ride, I got off at the entrance to Okunoin – a name literally meaning the innermost area of a temple’s grounds – a large, forested and wonderfully atmospheric precinct containing the mausoleum of Kukai himself and the tombstones of some 200,000 people making it the largest cemetery in all of Japan.

Crossing the Ichinohashi Bridge and making my way inside, I continued along a flagstone path surrounded by tall cryptomeria trees and an expanse of weathered, moss covered tombstones in a range of shapes and sizes.

It’s a testament to the devotion Shingon has inspired over the centuries that so many distinguished people from feudal lords to company presidents chose to be counted here among the faithful, in hopes of salvation in the life to come.

For fans of Japanese history, the cemetery can feel like something of a who’s who of the country’s warlike past, with the graves of Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin – two great samurai united in death after a lifetime at war with one another – as well as numerous members of the Tokugawa clan. Perhaps the two most exciting for me however belonged to Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Oda Nobunaga – both exceptionally powerful warlords who paved the way for a united Japan.

My final stop in Okunoin – at least for now – was outside the Gokusho or offering hall, where visitors can be seen pouring water from a sacred trough onto a row of Buddhist icons. Just beside this, the Gobyobashi Bridge leads over a narrow stream and into the most sacred part of the precinct, where the Torodo or lantern hall can be found along with Kukai’s mausoleum, known as the Gobyo – an area considered so sacred that food, drink and photography are not permitted past the bridge.

By now it was almost time to make my way to my accommodation for the night at a nearby temple, so I took a shortcut back towards the entrance through one of the newer plots of gravestones. This part of the cemetery is notable for several unique monuments, mostly belonging to companies and reflecting the nature of their work.

I would be staying at Ekoin, a grandly austere complex of buildings located just a few steps from the Ichinohashi Bridge. Said to date over 1,200 years to the community’s beginnings under Kukai, it prospered over the centuries thanks to the patronage of powerful samurai and was even given its name by the 8th Tokugawa shogun, Yoshimune.

After checking in, I was led by one of the monks down a series of corridors to my room for the night. As one of the temple’s higher grade rooms, it was a little larger than the standard size with a narrow veranda looking out onto a small enclosed garden. Now was not the time to relax however, as in just a few minutes it was time for the first of three very special experiences lined up for that evening.

Making my way to the temple’s Ajikan Hall, I took my place on one of a few dozen little circular cushions for a brief introductory meditation session taught by Nori-san, one of the monks in residence here.

With tangible gentleness and patience, our instructor explained that in this, the first of a series of stages in Shingon meditation, our task was simply to practice the correct posture and breathing, counting each breath in cycles of 10 while beginning to observe emerging distractions. As for the latter, Nori-san suggested visualizing them as pebbles in a garden – rather than pick each one up and examine it, we can easily detach ourselves by thinking of each one as small parts of a wider picture.

Feeling remarkably light and refreshed after my meditation experience, it was next time to try another popular highlight of a stay on the mountain: the special Buddhist cuisine known as shojin ryori, served in traditional fashion in a private tatami room.

Introduced from China in the 13th century by the monk Dogen, this simple yet refined cuisine quickly gained popularity among Buddhist monks and lay devotees alike due to its absence of meat, fish or animal products – aligning with the Buddhist tradition that frowns on the killing of living beings for food. Instead, shojin ryori highlights numerous variations on tofu together with seasonal vegetables and mountain plants.

Despite its apparent simplicity, each meal must be carefully balanced according to the so-called grule of fiveh – five colors, five flavors and five elements – in a way that harmonizes with the body, mind and season, and its principles continue to strongly influence contemporary Japanese cuisine.

By now I was feeling very full and relaxed, but with my evening just beginning, I set off with a group of my fellow guests at Ekoin for what promised to be a very atmospheric after dark tour of Okunoin. With Nori-san acting as our guide, we crossed the Ichinohashi Bridge into the cemetery, the tombstones seeming to close in on us from both sides lit only by lanterns, the occasional overhead lamp post and Nori-san’s flashlight.

In fact, as several other guests later agreed, the precinct had little of the unsettling quality one might experience in a Western cemetery or churchyard. If anything, I would compare the feeling to being in a vast, dark cathedral – that sense of peace and quiet awe that makes you want to whisper.

As we continued along the path, Nori-san would periodically gather us together to explain something, from the shape of Buddhist tombstones and other recurring symbols to how and why a person might be interred at one of the many corporate mausoleums. One point I was keen to find out was exactly what physical remains were placed in such tombs, when Buddhist families today usually receive the ashes of a deceased relative to bury locally. Nori-san answered that typically this would be only the Adam’s apple – known in Japanese as the “throat Buddha” and chosen for its resemblance to two hands joined in meditation.

Arriving at the Gobyobashi Bridge, our guide reminded us that food, drink and photography were forbidden beyond this point before leading us on to the Torodo, attractively lit by hundreds of lanterns, each one representing the soul of a single departed person.

We ended the tour at the foot of Kukai’s mausoleum, with a few words from Nori-san about the founder’s life and work. Fascinatingly, it is said that he is not dead but rather sitting in eternal meditation, with monks continuing to bring offerings of food to his door twice every day.

With the tour over, I retraced my steps back through the cemetery to Ekoin and was delighted to be back in my warm, cozy room for the night.

After a peaceful night’s sleep, the next day began at 7:00 with morning prayers in the temple’s main hall, where statues of Amida Nyorai, Kukai and the stern faced fire deity Fudo Myoo are set behind a grand, elaborate altar festooned with sacred objects.

Taking a seat in front of the altar alongside a few other overnight guests, I listened as two priests performed a long, rhythmic chant interspersed with curious ritual movements and the smell of incense, putting me in a reflective mood for the day ahead.

Next, I made my way to the Bishamon Hall for the chance to witness another fascinating practice unique to Shingon Buddhism – the goma gyo, or fire ritual. In this dramatic ceremony, a priest burns slim wooden sticks in a specially consecrated fire, symbolizing human desires consumed by the wisdom of the Buddha.

Performed by the temple’s chief priest, this second ritual had a power to it that was hard to put into words, with roaring flames, the crackle of burning leaves, more rhythmic chanting and pounding drums all mixing together into an intense, cathartic wave.

After taking in those two ceremonies, it was time to sit down to a beautifully prepared shojin ryori breakfast, served in the same private tatami room as dinner the previous night. Resembling a stripped down version of yesterday’s meal, this once again included tofu, white rice, a bowl of rich miso soup, boiled vegetables and a sweet, perfectly ripe tangerine.

Physically as well as spiritually nourished, it was time to leave Ekoin behind and set out for another day of sightseeing on the mountain, beginning with a visit to the nearby temple complex of Kongobuji.

Serving as the headquarters of the Shingon faith, Kongobuji was originally constructed in 1593 by the warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi in commemoration of his late mother. In fact, this was quite a turnaround as he is said to have originally planned to attack and destroy the monastery, and was only persuaded to change his mind after determined negotiation by the monk Ogo, colorfully known as the gwood eating sainth.

Making my way through the main gate, I was immediately struck by the stately look of the main building, with elegantly sloping roofs and elaborately carved designs featuring dragons and floral patterns.

Inside the temple, the first major room I came to was the Ohiroma, used for important ceremonies and decorated with a series of cranes painted by members of the famous Kano School. Immediately next to it are the plum and willow rooms – the latter known as the place where Toyotomi Hidetsugu – a chief advisor to the imperial family and Hideyoshi’s own nephew – committed seppuku on the warlord’s orders.

Continuing deeper inside, I found myself in a series of elegant spaces, from richly furnished tatami rooms to open veranda looking out onto courtyards or neatly enclosed gardens.

Another outstanding highlight is the Banryutei dry rock garden – the largest of its kind in all of Japan – enclosing a special inner sanctuary known as the Okuden. Created 40 years ago using only raked gravel from Kyoto and stones imported from Shikoku, where Kukai was born, the garden represents twin dragons emerging protectively from a sea of cloud.

For my last stop on Koyasan, I took a short walk from Kongobuji to the central temple complex, called the Garan. Towering over the other buildings is the 45 meter tall Konpon Daito Pagoda, built in 1937 and painted in brilliant vermillion. Inside, the building centers on statues of Dainichi Nyorai – the Cosmic Buddha – surrounded by four smaller buddhas and a series of colorfully painted pillars, forming a dazzling three dimensional representation of a mandala.

With that, my time on Koyasan was at an end, and I began to retrace my steps back the way I had come from central Osaka, once again using the digital ticket from Nankai Electric Railway to cover each stage of the journey. Although this wasn’t my first time on the mountain, it had been my first experience of staying overnight at a temple, and this extra time – combined with genuinely profound and absorbing activities like the meditation session and guided tour of Okunoin – made all the difference.

To anyone currently planning a trip and still on the fence about visiting this fascinating and uniquely atmospheric destination, I would certainly say that the effort in making the trip is likely to be well rewarded – and I hope that you find the experience as inspiring as I did.