Before receiving

Brutalist Paris from the folks at Blue Crow Media, I thought of the UK company simply as a maker of maps.

I reviewed Concrete Map Chicago back in 2018 and since then have noticed them putting out maps of

modern architecture,

brutalist architecture,

public transit —

even trees. If the Chicago map is any indication, the others put out by Blue Crow Media excel at assembling a mix of quality buildings and presenting them in a way that allows people to orient themselves to the locations of the selected buildings in a particular city; that’s the power of maps: orienting oneself physically, in place,

and mentally, at a distance. So I was a bit surprised to find the maps on the inside front and back covers of

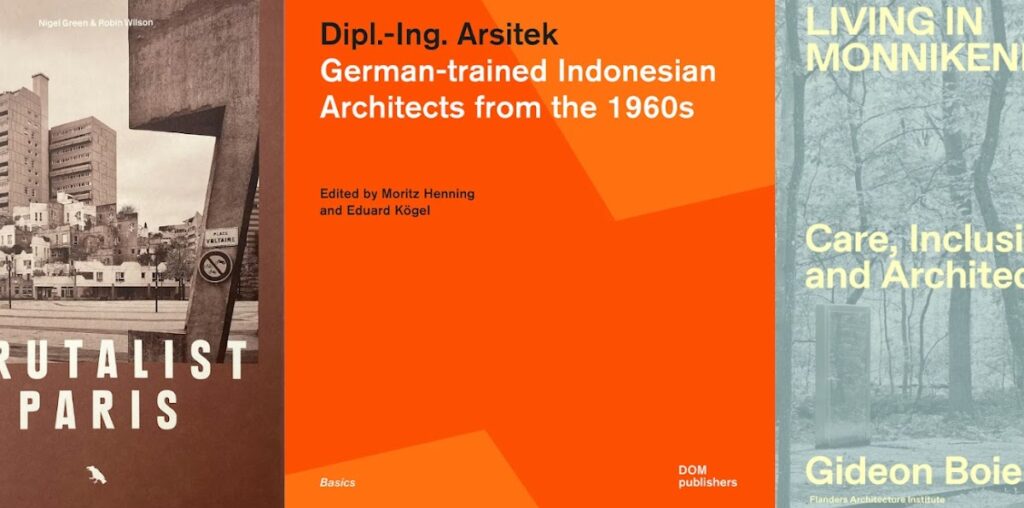

Brutalist Paris to be, frankly, practically useless. Their scale is too small; the contrast between streets and blocks is too low; it’s not clear how the four maps join up; the lists of buildings keyed to the maps do not extend to the book’s pages. I could go on, but that’s not necessary because this book is not about the maps. Rather it is about the words of Robin Wilson and the photographs of Nigel Green. The maps give some cursory, almost ghostly, geographic information, but they are not there to structure the book.

Brutalist Paris features seven essays by Wilson and four geographical sections with Green’s photos inserted between the essays. Although the duo collaborates as

Photolanguage, words and images are distinct. “Whilst the photographic component provides an extensive, general survey of the production of the period as a whole,” Wilson explains in the first essay, “the text necessarily develops a more selective interpretation of a smaller range of key works.” Paris does not spring immediately to my mind as the city of brutalist architecture

par excellence (that would be London or Boston), but Wilson’s words and Green’s images do a good job of arguing for the importance of Paris as a brutalist city. Jumping to the fore are, not the famous examples (Breuer’s UNESCO, Niemeyer’s Communist Party HQ, Corbu’s Maisons Jaoul), but the complex, fractal-like constructions of Jean Renaudie and Nina Susch, Renée Gailhoustet, and others. Wilson describes “a properly oblique and combinatory architecture” and Green captures the light, scale, and in some cases decay of the complexes. The photos may be just a couple of years old, but the choice of presenting them as duotones helps transport readers to the sixties, seventies, and eighties, when parts of Paris really embraced creative concrete architecture.

The next book covers roughly the same timeframe as

Brutalist Paris — the few decades following the year 1960 — but in two locales thousands of miles and two continents apart: Indonesia and Germany. The two places don’t immediately strike me as intertwined, but editors Moritz Henning and Eduardo Kögel discovered a link between them that is quite interesting: a dozen architecture students from Indonesia who studied at TU Berlin and other schools in West Germany in 1960/61. The editors found out about them while working with the curators of

Occupying Modernism, the Indonesian contribution to

Encounters with Southeast Asian Modernism, an ambitious, multifaceted program directed by Henning and Kögel with Sally Below and Christian Hiller. (Out of the same program came

Contested Modernities: Postcolonial Architecture and the Construction of Identities in Southeast Asia,

a publication I “briefed” last year.) Like other parts of

Encounters,

Dipl.–Ing. Arsitek focuses on cross-cultural cooperation between Southeast Asia and Western Europe, and it even comes across subtly in the book’s title, words that are probably enigmatic to English speakers:

Dipl.–Ing. Arsitek is the Indonesian equivalent of the German

Diplom–Ingenieur Architektur.

Dipl.–Ing. Arsitek is number 171 in

DOM Publishers’ longstanding

“Basics” series as evidenced by the square format and orange, geometric cover (

like this one). While the subject seems too niche to me to be a “basics” book, the structure and presentation of the book are very clear and well done, aiding in one’s understanding of the subject and recognizing its importance. Following spreads of period photographs in West Berlin, Hannover, Aachen, and Jakarta, the book’s contents are fitted into five parts: “Context,” with a handful of essays give relevant background on Germany and Indonesia in the period of the book; “Diplomas,” a presentation of ten of the students’ final projects; in-depth “Biographies” of eight of the architects; “Positions,” excerpts of a few texts by some of the architects; and contemporary “Photographs” of buildings in Indonesia the architects designed after returning there to practice. So, who are these architects that studied in Germany but took their knowledge back home to Indonesia? Soejoedi Wirjoatmodjo and Han Awal were known by the editors beforehand, but the rest (Herianto Sulindro, Jan Beng Oei, Mustafa Pamuntjak, Bianpoen, Suwondo Bismo Sutedjo, Yusuf Bilyarta Mangunwijaya) were primarily discovered in the archives of TU Berlin, which kept their drawings, model photographs, and even some of the models. I can’t think of a better arguments for architecture schools — and the future architects attending them — to carefully document their thesis projects and maintain them in archives.

The third place-in-time book, Living in Monnikenheide, heads to Zoersel, in Belgium, and jumps forward in time to near the present. The book’s subject, Monnikenheide, is a residential care center for people with mental disabilities that was created around 1973 and has seen more than a dozen buildings added to its “campus” in the half-century since. I had never heard of the place — neither Monnikenheide nor Zoersel, the Flemish village now home to around 22,000 people — so reading some of the essays and perusing the case studies of the buildings were acts of discovery. Gideon Boie, the book’s editor and instigator of the book project, describes Monnikenheide as “an unprecedented housing project” that “searched for the normalization of housing for people with mental disabilities” and, in wording that echoes recent trends in architectural culture, “a testing ground for care architecture.” The book’s subtitle, Care, Inclusion and Architecture, sets up the half-dozen essays that carry the titles “Living with Disability,” “At Home in the Care Centre,” and “Caring for the Landscape of Care,” among others. The essays capably address the myriad issues around the place, from its niche typology to the politics of “inclusion” and the important role of the beautiful wooded landscape connecting the various buildings.

The bulk of the book — 70 of its 160 pages — is devoted to the case studies of the buildings, primarily the ones built between 1997 and 2021; the early, “first-period” (of three periods, per Boie) buildings are just described briefly at the beginning of this long section. Architecturally, the buildings range from somewhat typical modern Belgian brick dwellings to low-slung glass-walled updates to older buildings, pitched-roof care homes clad in corrugated metal, and a three-story care home covered in blackened wood. While each building is pleasing in one way or another, Monnikenheide is not about any individual building: it is about the interaction of the buildings with each other and the landscapes between them and, in the case of the brick dwellings in the village, the logical extension of “inclusion” to a context more urban than pastoral. Full-bleed photographs between the different sections of the book do a decent job in capturing the character of the landscape and the village; I say “decent” because their silver duotones, akin to the cover, are more aesthetic than informative. But in concert with the essays, case studies, and the book’s design, the photos contribute well to a beautiful document of a special place that architects interested in this facet of care will find valuable.