Update (October 28. 2024)

Comet ATLAS has indeed not survived perihelion. The Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) captured its demise.

The original story, published October 9th, appears below.

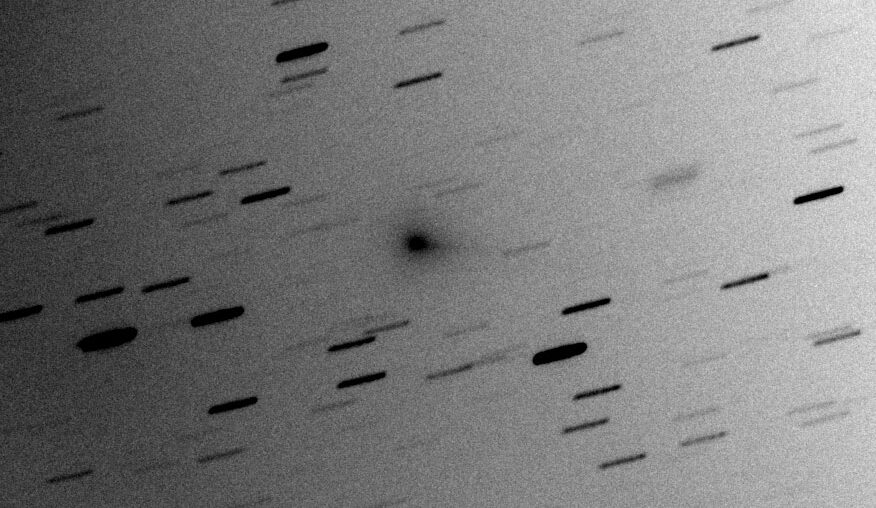

Andrea Aletti and Luca Buzzi (Schiaparelli Southern Observatory)

We still don’t yet know how much of a show we will get from the long-anticipated peak time for Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS (C/2023 A3), but now, that bright comet is about to have company. By the end of the month, the newly discovered Comet ATLAS (C/2024 S1), also found by the ATLAS survey on Haleakalā, Hawai‘i, by some accounts has the potential to appear as bright as magnitude –8 — brighter than Venus — but only very briefly, and with high degrees of uncertainty.

Comet ATLAS (C/2024 S1) was just discovered on September 27th, when it was still about 1.2 million kilometers (750,000 miles) from the Sun. Astronomers quickly determined that it’s a member of the Kreutz family of sungrazing comets, which are all thought to be remnants of a single, giant comet that disintegrated after a long-ago perihelion passage.

Sungrazing comets can become brilliant near the Sun but, while media headlines have been touting this one as a possible daytime comet, there’s a good chance it may not even make it past its closest approach to the Sun, or perihelion, on October 28th without disintegrating. Experienced comet observer and former S&T columnist John Bortle, who has recorded observations of more than 300 comets, tells Sky & Telescope that this comet “is simply too faint to likely survive its passage through the solar inferno of perihelion.”

Bortle puts the comet into context based on a detailed analysis he conducted 30 years ago, looking at the records of every sungrazing comet going back to 1843. He rated each comet by its absolute magnitude, H, the visual brightness it would have if it were 1 astronomical unit away from the Sun and 1 au from the observer. Those comets with magnitudes fainter than 7 did not survive their closest approach to the Sun. This one has an absolute magnitude of 11, much fainter than the threshold. The current brightness, Bortle says, gives this one “no shot at all, in my opinion.”

But even if it doesn’t actually survive its brush with the Sun, this comet could still put on a dramatic show. That was the case with the Great Comet of 1887 (C/1887 B1), and with Comet Lovejoy (C/2011 W3) in 2011, both of them sungrazers that brightened dramatically before perihelion but survived only as tail remnants.

“[Comet Lovejoy] totally broke-up/vaporized just an hour or two following perihelion passage,” Bortle says, “generating the beautiful headless isolated tail feature seen from the southern hemisphere.” But Lovejoy was likely one of the larger pieces of Kreutz “debris.” The chances of Comet ATLAS being visible to the unaided eye are unlikely even on its way in toward the Sun.

Dan Green (Harvard University), who runs the International Astronomical Union’s Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams and has extensive comet-watching experience, tells Sky & Telescope that while he agrees with Bortle’s assessment of Comet ATLAS’s odds, he is nevertheless not as pessimistic about its potential to be a dramatic sight.

Green agrees with Bortle that the comet will break apart. “Most sungrazers do not survive perihelion,” he says. “Only the very largest have.”

Nevertheless, he cites Comet Ikeya-Seki (C/1965 S1) as an example of what could happen: That object did in fact break apart into at least three pieces as it rounded the Sun, yet it was one of the brightest comets of the last 1,000 years, peaking at magnitude -10 — equivalent to the brightness of a quarter-moon. “It did survive perihelion, and it had a very long tail,” he says.

“Some of the brightest comets of the last two or three centuries have been Kreutz sungrazers,” he says. And in this case, excitement has been building partly because the comet was discovered a month before its perihelion. Most such comets are only found by the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) satellite once they are already only a few solar radii from the Sun.

Some of the uncertainty in predicting the comet’s future behavior stems from uncertainties in its present brightness, Green adds, which has been measured to be between 11th- and 16th-magnitude.

Amateur astronomer and avid comet observer Mike Olason, who observed Comet ATLAS from the Tucson area, tells Sky & Telescope that “it’s not as bright as some have suggested.” He used Astrometrica, a software program that uses hundreds of comparison stars to determine magnitude, to peg its brightness at magnitude 13.9 on October 1st. “There’s nothing to say it can’t brighten a lot this month,” he says. But if it’s really that faint still then “we need to be careful about raising the alarm for the public,” he says.

F. Manzini et al. / Astronomer’s Telegram #16857

It’s very possible this comet will disappoint. “A number of the latest observational posts are suggesting that the magnitude of C/2024 S1 has been slowly but steadily fading,” Bortle says. One observer even reported that the comet appeared elongated, suggesting it might already be breaking apart. “This would not be unexpected for a small fragment approaching the Sun perhaps for the first time,” he adds.

While there may only be a slight chance of seeing a “headless tail” after the nucleus falls apart, Bortle thinks it’s “not out of the question, I suppose.” It won’t be easy to see, though: The tail would be low over the southeastern horizon, pointing slightly downward, he says. It might be a better object for Southern Hemisphere observers.

In any case, if the comet does put on a good performance, the public can be quickly alerted to it.

“Let’s hope that it holds together long enough that we can see a nice tail out of it,” Green says, “and maybe have a nice show before it dies at perihelion.”