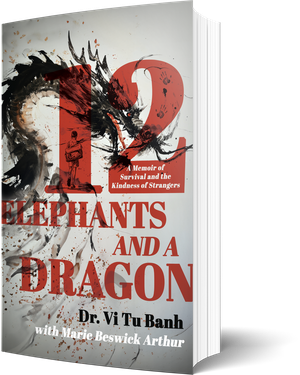

The author grew up listening to his storytelling grandfather, who was a great source of wisdom. “There was always a sense of purpose with his stories,” recalls Banh, “that they must be kept preserved, leaves pressed between pages, to hold together the promise of the cycle of life.” Little did he know at the time that his own story would soon turn into an epic journey worthy of a folktale. His family made and sold clothes in Saigon, but life grew precarious after the city fell to the North Vietnamese, who promptly renamed the capital Hồ Chí Minh City. After four years of deteriorating conditions, his eight-member family managed to flee the country—their only transport option was a small, rotting, overcrowded boat. Their harrowing journey would take them to refugee camps in Indonesia and eventually on to Canada, where a group of residents in Uxbridge, Ontario, banded together to sponsor their resettlement. The second half of the book follows Banh’s life after moving to Canada, including the long shadow cast by his experiences on the boat. Banh’s memoir serves as both a piercing account of his family’s arduous yearslong plight and an ode to the kindly Canadians who helped them start a new life in a new land. The author’s effusive attitude and understated prose keep the story from ever getting too heavy. At one point, during an ayahuasca trip meant to cure him of a urinary problem, he views a vision of the Buddha: “I looked up at Buddha and Buddha spoke to me inside my head. They were not words in any language I knew, and not like a download might work on a computer, not how some people say ideas arrive through energy. But Buddha spoke: ‘You can get off the boat now, Boy. It is time.’” There may be no neat ending to exile, but Banh has managed to shape his experiences into a wise and affecting tale.