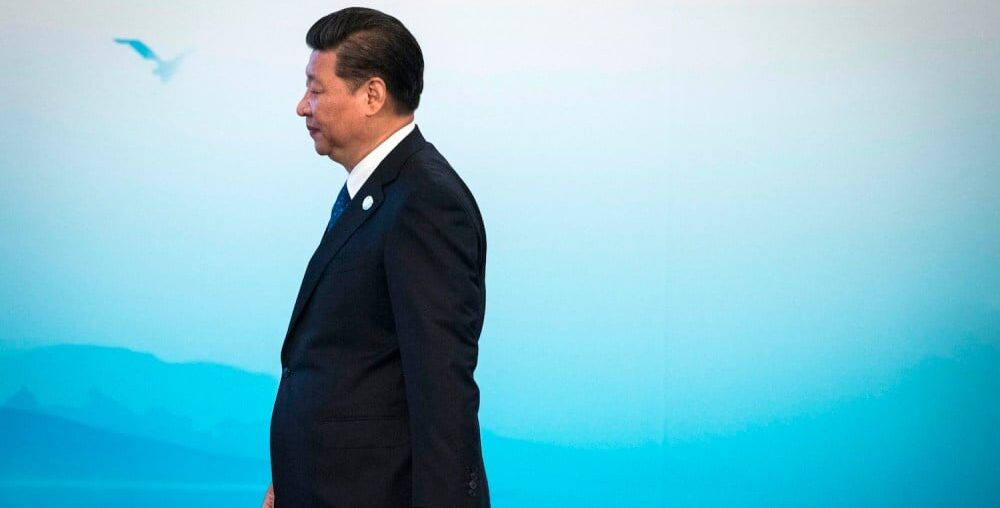

What will happen to China’s long-term ideological direction once President Xi Jinping eventually leaves the scene? This is unlikely anytime soon. But for a septuagenarian, the possibility is real enough to force us to start seriously thinking this through. Indeed, it goes to the core question of whether the deep structural and cultural changes that Xi has wrought will endure under the next generation of Chinese leaders. Could his particular brand of “Marxist nationalism”—marked by left turns in politics and economics, while moving foreign policy to the nationalist right—become more extreme as a younger generation of Xi political loyalists carry his banner forward? Or will “Xi Jinping Thought” fade, gradually at first, as happened with Maoism between 1976 and 1978, before it was finally repudiated by Deng Xiaoping and his successors?

Post-Xi China will be shaped by a number of factors, the most important of which will be timing. Xi will want to stay in office until he is confident that the generation to succeed him in the party’s most senior leadership positions will share his ideological direction and zeal. This presents a problem. Xi constantly rails against his own generation and the one immediately below him for having allowed corruption, careerism, and ideological confusion to reign supreme. That’s why his party rectification campaigns have been designed to instill personal and political fear and rigor.

What will happen to China’s long-term ideological direction once President Xi Jinping eventually leaves the scene? This is unlikely anytime soon. But for a septuagenarian, the possibility is real enough to force us to start seriously thinking this through. Indeed, it goes to the core question of whether the deep structural and cultural changes that Xi has wrought will endure under the next generation of Chinese leaders. Could his particular brand of “Marxist nationalism”—marked by left turns in politics and economics, while moving foreign policy to the nationalist right—become more extreme as a younger generation of Xi political loyalists carry his banner forward? Or will “Xi Jinping Thought” fade, gradually at first, as happened with Maoism between 1976 and 1978, before it was finally repudiated by Deng Xiaoping and his successors?

Post-Xi China will be shaped by a number of factors, the most important of which will be timing. Xi will want to stay in office until he is confident that the generation to succeed him in the party’s most senior leadership positions will share his ideological direction and zeal. This presents a problem. Xi constantly rails against his own generation and the one immediately below him for having allowed corruption, careerism, and ideological confusion to reign supreme. That’s why his party rectification campaigns have been designed to instill personal and political fear and rigor.

This article is adapted from On Xi Jinping: How Xi’s Marxist Nationalism is Shaping China and the World by Kevin Rudd (Oxford, 624 pp., $34.99, October 2024).

Xi will likely remain cautious about trusting anyone to replace him who entered a significant position of political authority under his predecessors. He would also be dubious as to whether they have sufficient personal commitment to continue his ideological and political program into the future. His instinct would be to remain in power until a critical mass of younger party officials, who began their university education under him, have reached higher political office. Xi’s constant invocation to “dare to struggle” (ganyu douzheng) has been delivered through the country’s party school networks and has been particularly focused on younger cadres. In doing so, Xi has appealed to their youthful idealism, as yet uncorrupted by the rampant materialism and bourgeois influences of the recent past.

However, this effort to purify the future ranks of the party’s leadership would mean relying primarily on cadres born after 1995, who were children when Xi first came to power. By the 22nd Party Congress in 2032, however, “Xi’s generation” would be at most 37, barely old enough in normal circumstances to be appointed as alternate Central Committee members. At the two subsequent congresses in 2037 and 2042, when Xi would be in his 85th and 90th years, they would be in their mid-40s—the optimum age for placing this rising generation of young Chinese nationalists into positions of real authority, even possibly the Politburo. In other words, it would take a long time to appoint large numbers of this post-“reform and opening” generation to the highest positions in the party.

While there will be other ideological conservatives and personal loyalists in the senior ranks of the party whom Xi would trust, this younger generation presents his greatest hope and political bulwark against ideological revisionism once he leaves the scene. They would provide the ballast of political support across the central party leadership that his designated successor would need to avoid being ousted from power. Therefore, the longer Xi remains in office, the more likely his succession plan will be able to deliver long-term ideological continuity.

Chinese politics after Xi will also be affected by the unfolding geopolitics and geoeconomics of the decade ahead. By far, the most important external strategic development will be the future of Taiwan. If U.S. deterrence fails—either through insufficient U.S., Taiwanese, and allied military capability or a failure of U.S. political will—and Xi swiftly and (relatively) bloodlessly takes Taiwan by force, his position within Chinese domestic politics would become unassailable. Xi would have achieved what Mao had failed to achieve by reuniting the motherland. Xi would then, most likely, launch what would be framed as a new age of Pax Sinica as U.S. geopolitical decline set in across Asia and, in time, the world. Taiwan would be seen within China and the wider region as a profound geopolitical tipping point.

Domestically, this would afford Xi a maximally advantageous set of circumstances to secure both his desired political succession and the continuation of his ideological legacy. If, by contrast, Xi sought to resolve Taiwan by force and was defeated militarily, there is little doubt he would be forced from office. Such a defeat, coming after more than a decade of official propaganda that only Xi had made China powerful, would count as national humiliation of the highest order. It would, therefore, demand the highest political price be paid. Indeed, the legitimacy of the regime itself would come under direct challenge.

However, the third—and, at this stage, most likely—scenario is that deterrence continues to hold through the 2020s and war is avoided. In this case, Taiwan would mean little for Xi’s longer-term internal succession planning.

Equally important, if the famously assertive and status quo-challenging Xi ultimately judged that the risks were still too great to take Taiwan by force, it is highly unlikely that his successors would then be prepared to do so. Alternative diplomatic frameworks for long-term national unity may, under these circumstances, become possible in a new generation of negotiations between Beijing and Taipei. For these reasons, given his desire to surpass Mao’s achievements on national reunification, and to do so before the People’s Republic of China’s centenary in 2049, Xi’s time in office likely represents the period of peak danger regarding the possibility of war over Taiwan. Navigating the Taiwan question through effective deterrence during the Xi period remains the single most critical strategic task for supporters of the status quo—the focus of my previous book, The Avoidable War.

The dominant internal political dynamic within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) after Xi ultimately leaves the stage will, most likely, be part of the long-standing processes of natural self-correction that lie within the party itself. Throughout its history, the CCP has oscillated between left and right, conservatives and reformers, isolationists and internationalists—a phenomenon of “control and release” (fangzhou). In the post-1949 period, for example, Mao’s leftism dominated with an emphasis on class struggle, the anti-landlord movement, collectivized agriculture, and nationalized industry. This was until the 8th Party Congress in 1956, when pragmatists sought to readjust the party’s center of economic gravity to promote steady economic development, trade, and commerce. Mao retaliated with the Great Leap Forward in 1958, resulting in widespread famine as he sought to accelerate industrialization at the expense of normal agricultural production. The economic pragmatists, then led by Deng, went on the offensive in the early 1960s, and Mao pushed back with the Cultural Revolution, purging his “rightist” political opponents and doubling down on both agricultural and industrial collectivization. This ended with Mao’s death in 1976, the formal repudiation of Mao’s leftist errors, and Deng’s initiation of what would become a 35-year era of reform and opening, which reembraced the private sector for the first time in decades.

Xi is likely to have seen this long series of historical debates within the CCP as the inevitable product of internal dialectical confrontation, contradiction, and struggle to establish the “correct” party line. Hence his efforts since 2012, and particularly after 2017, to correct the economic and social imbalances left over from the Deng era. The political and economic momentum already building against Xi’s leftist ideological project is formidable. But as with Mao, it is unlikely to be strong enough to force any fundamental political correction until the leader has formally departed the scene. Xi is undoubtedly aware of the danger of self-correcting forces in whatever interim leadership may replace him, fueling his recruitment of younger, more idealistic, and nationalistic cadres into the leadership echelons of the party as early as possible.

Xi’s problem, however, is that he may not have enough time. He would probably have to maintain power well into his 90s to appoint enough ideologically reliable younger cadres to enable his political strategy to take root. Pitted against this strategy will be the underlying forces of political inertia, bureaucratic entropy, and a party historically predisposed to return to the political mean. Even for a formidable politician like Xi, prevailing in such a long-term struggle against the political, economic, and social forces arrayed against him will be a tall order indeed.

The irony, therefore, is that Xi, the master dialectician, could well be defeated by dialectical forces of his own making—a direct reaction to decades of his own ideological overreach. Unless Xi can hold on for another 20 years or more, China is less likely to become more ideologically extreme once he goes. The country after Xi, as in previous eras in modern Chinese history, will probably welcome a correction toward the center, given how much of Xi’s ideological project has grated against so many individual aspirations, societal norms, and deep economic interests in modern China—as well as giving rise to concern, at least among elites, as to how isolated China has become from much of the world.

For these reasons, the challenge for the wider world is to effectively navigate the Xi era through a combination of deterrence and diplomacy, without recourse to crisis, conflict, and war. War, whatever its outcome, would generate death and destruction at an unimaginable scale. It would also redefine Chinese, American, and global politics and geopolitics in deeply unpredictable ways. And the world would never be the same again.

From On Xi Jinping by Kevin Rudd. Copyright © 2024 by Kevin Rudd and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.