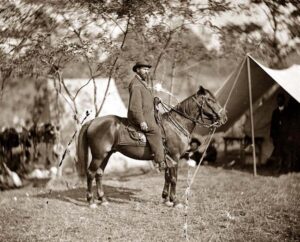

![William A. Pinkerton with railroad special agents Pat Connell (left) and Sam Finley (right), full-length portrait]](https://www.thehistoryreader.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/pinkertons-217x300.jpg)

Even if you’ve only watched a handful of “Wild West” films or TV shows, you’ve probably encountered the Pinkertons. These hired guns are often mistaken for police, but they rarely carry official badges. Instead, Pinkerton detectives are cast as ruthless mercenaries of big business, pledging their muscle to the highest bidder. In HBO’s Deadwood (2004-2006), they work undercover to guard the interests of a mining tycoon. In The Long Riders (1980) and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007), the Pinkertons chase down the James-Younger gang on behalf of banks and railroads.

But perhaps the most visible pop-culture showcase of the Pinkertons came not in a film or television show but a wildly popular video game: Red Dead Redemption II. With over sixty million copies sold, it’s the most commercially successful historical video game ever made. In its sweeping storyline, the Pinkertons feature prominently. They relentlessly pursue the game’s protagonists, the van der Linde gang, on a contract from a eastern robber baron. Within the game, the Pinkertons are the western outlaw’s most feared adversary, symbolic of the closing of the “Wild West” era.

This depiction of the detective agency does not differ from the film and TV portrayals listed above. But what is different is the timing. Each of these Hollywood and TV renditions portray the Pinkertons in the 1870s or early 1880s, when the agency was renowned as western bandit-hunters. But Red Dead Redemption II is set a generation later, in 1899. As it turns out, this chronological gap matters a great deal – because the Pinkerton agency is one that changed dramatically over time, and its history can shed light on the towering dilemmas of Gilded Age America.

The agency is inseparable from its larger-than-life founder, Allan Pinkerton. Born in 1819 to a humble family in Glasgow, Scotland, Pinkerton came of age during the Chartist movement for working-class rights – and he deeply sympathized with their cause. Such sympathies landed Pinkerton in hot water when the British government cracked down on Chartism, forcing the young Scot to flee to the United States in the early 1840s. Settling in Illinois, Pinkerton established a private detective agency called the North West Police Agency. During the Civil War, he pledged his bureau into service for the Union, working in military intelligence and sleuthing to uncover Confederate plots. The war supercharged the business and saw the agency reborn as “Pinkerton’s National Police Agency” – reflecting the founder’s growing ambitions and ego.

The Pinkerton agency’s first contracts were with express companies, firms moving gold and valuables across the mountains and plains of the West. Such contracts placed Pinkerton in the crosshairs of a range of bandit gangs, most famously Jesse James and his brood, whose bloody vendetta with the agency in 1874-75 became renowned. Pinkerton was a masterful publicist, spinning his agency’s real-life adventures into legend through the new medium of dime novels; he wrote more than seventeen books in just nine years.

But in 1884, Allan Pinkerton died, both unexpectedly and bizarrely, biting his tongue in a fall and later perishing from gangrene. After his death, his agency marched on – but to a different tune. The company’s leadership now fell to his sons, Robert and William, who shared a last name with their father but little else. Unlike Allan, who since his Chartist days had held an idealistic sympathy for working-class people, Robert and William had grown up in the lap of luxury. They sought to reinvent their father’s agency as a hired army for America’s wealthiest industrialist, pursuing not bandits but labor unions and striking workers.

In the following two decades, the Pinkertons earned a second reputation – not as beloved outlaw-hunters but as hated union-busters and strike-breakers. In bloody standoffs like Pennsylvania’s Homestead Strike and Idaho’s Coeur d’Alene Strike, both in 1892, the Pinkertons became the bogeyman of the American working class, a despised institution that symbolized how a new power elite used their money to corrupt law and justice.

Therefore, if Red Dead Redemption II were to accurately portray the Pinkertons of 1899, it would be more fitting to have the van der Linde gang confront their antagonists among the pickets of striking workers, not the aftermath of a train robbery. But video game developers – like film and TV directors before them – are often reluctant to foreground labor unrest in their work since this remains a hot topic today. Rockstar Games, the creator of Red Dead, faced stinging accusations in 2018 of fostering a toxic culture of overwork in the months leading up to the game’s release.[1] And the Pinkertons continue to operate today, recently making headlines for their surveillance of Amazon employees looking to form labor unions.[2] All of this reaffirms what the novelist William Faulkner once wrote: “the past isn’t dead. It’s not even past.”

[1] Jason Schreier, “Inside Rockstar Games’ Culture of Crunch,” Kotaku, October 23, 2018, https://kotaku.com/inside-rockstar-games-culture-of-crunch-1829936466.

[2] NPR, “Amazon Reportedly Has Pinkerton Agents Surveil Workers Who Try To Form Unions,” November 30, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/11/30/940196997/amazon-reportedly-has-pinkerton-agents-surveil-workers-who-try-to-form-unions.

![William A. Pinkerton with railroad special agents Pat Connell (left) and Sam Finley (right), full-length portrait]](https://myspacemyanmar.org/myspace.com.mm/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/The-Pinkertons-in-Myth-and-History-The-History-Reader-462x508.jpg)