Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS (pronounced “tzeh-chin-SHAHN”) continues to shrink and fade as it recedes into the distance in the western sky right after nightfall. It’s still a fine target for binoculars and telescopes, moderately high in Ophiuchus in moonless darkness. See Bob King’s latest update, Grab Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS by the Tail, including a finder chart running through November.

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 25

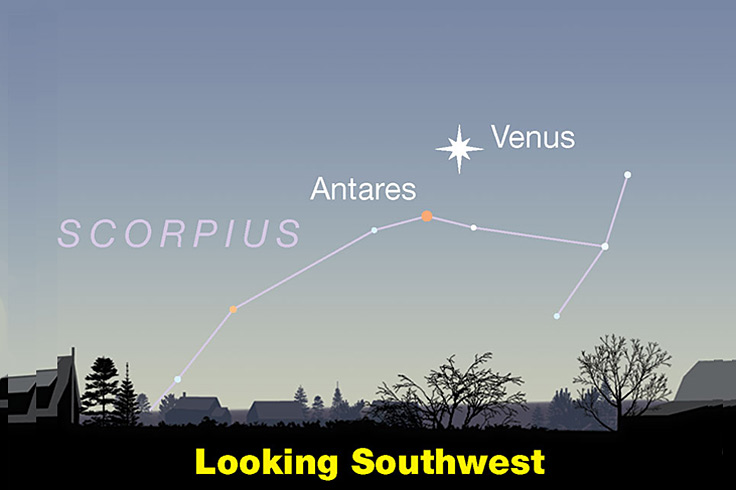

■ Venus is in conjunction with orange Antares low in twilight, as shown below. Venus is 100 times brighter than Antares; look for a tiny orange point 3° to Venus’s lower left. Binoculars can help you spot it through the twilight and the thick air near the horizon.

■ The Ghost of Summer Suns. It’s almost Halloween, and this means that Arcturus, the star sparkling low in the west-northwest in twilight (about five fists to the right of Venus), has taken on its role as “the Ghost of Summer Suns.” For several evenings centered on October 25th every year, Arcturus occupies a special place above your local landscape. It closely marks the spot where the Sun stood at the same time, by the clock, during hot June and July — in broad daylight, of course!

■ The cup-shaped waning crescent Moon rises in the east-northeast around 2 a.m. Saturday morning, followed 20 or 30 minutes later by Regulus below it. By the time Saturday’s dawn begins, you’ll find them high in the east-southeast and closer together.

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 26

■ Altair is the brightest star high in the southwest after dark. Brighter Vega is about three fists to its right, high toward the west.

Above Altair lurk two distinctive little constellations: Delphinus the Dolphin, hardly more than a fist at arm’s length to Altair’s upper left, and smaller, fainter Sagitta the Arrow, slightly less far to Altair’s upper right. If your sky is too light-polluted, try binoculars.

SUNDAY, OCTOBER 27

■ Draw a line from Altair (high in the southwest) to the right through Vega, and continue the line onward by half as far. There you are at the Lozenge: the pointy-nosed head of Draco. His nose points back to Vega.

MONDAY, OCTOBER 28

■ More about Altair: Just upper right of it now, by a finger-width at arm’s length, is orange Tarazed (Gamma Aquilae), Altair’s eternal little sidekick. It’s a modest magnitude 2.7 compared to Altair’s showy 0.7. But looks are deceiving. Altair looks so bright because it’s one of our near stellar neighbors, just 17 light-years away. Tarazed is an orange giant star about 380 light-years farther behind — and 170 times as luminous!

■ In the early-morning hours of Tuesday and Wednesday the 29th and 30th, Mars in the eastern sky is just about perfectly lined up with Pollux and Castor. Hold a ruler up to them to judge the straightness of the line.

TUESDAY, OCTOBER 29

■ Can you find M33, the Triangulum Galaxy, the closest large galaxy to us after the famous one in Andromeda? It’s a good deal dimmer, with a low surface brightness that needs a dark sky. But in such a sky I find that it’s a fairly easy target in 10×50 binoculars. It’s about a third of the way from Alpha Trianguli (the sharp point of the Triangle) to Beta Andromedae (the middle star of Andromeda’s main line of three). While the evenings are still moonless, check out the precise finder chart and Matt Wedel’s Binocular Highlight column about M33 in the November Sky & Telescope, page 43.

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 30

■ When night arrives now, the Great Square of Pegasus is still balanced on its corner very high in the southeast. But within two hours it turns around to lie level like a box very high toward the south.

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 31

■ This year Halloween evening is moonless, but it offers three bright planets. While twilight is still fading, catch Venus very low in the west-southwest. After dark, Saturn is the brightest little dot high toward the south-southeast. (Don’t confuse it with Fomalhaut, sparkling two fists below it.)

And by about 10 p.m., Jupiter has climbed up to dominate the east.

FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 1

■ November fireballs? Every year from about late October through mid-November, a truly dazzling Taurid meteor just might take you by surprise in the night. If you get very lucky.

Normally the broad, weak, South and North Taurid meteor showers sputter along sparsely. Under ideal conditions you might see 5 or 10 ordinary little meteors per hour during the poorly defined, weeks-long maximum when the two branches of the shower overlap. Both include debris shed by Comet 2P/Encke, but a recent analysis shows that a host of other objects — near-Earth asteroids, collisional fragments, and dormant cometary nuclei — might be creating several overlapping streams of particles. Consequently, both Taurid components have long-lasting “maxima” that aren’t easy to pin down.

What makes the Taurids potentially exciting is that their small numbers are known for a high proportion of bright fireballs — occasionally, an extremely bright one that makes the news.

The Taurids strike the atmosphere at a relatively slow 19 miles (30 km) per second. If you see an especially bright, slow meteor these nights, check whether its line of flight, if traced backward far enough across the sky, would intersect more or less the Pleiades side of Taurus.

■ New Moon (exact at 8:47 a.m.)

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 2

■ Algol in Perseus, high in the east, should be in mid-eclipse, magnitude 3.4 instead of its usual 2.1, for a couple hours centered on 10:42 p.m. EDT; 7:42 p.m. PDT. Algol takes several hours to fade beforehand and to rebrighten after. Comparison-star chart, with north up. Celestial north is always the direction in the sky toward Polaris. Outside at night, turn the chart around to match.

At any random time you look up at Algol, you have only a 1-in-30 chance of catching it at least 1 magnitude fainter than normal.

■ Daylight-saving time, observed in most of North America, ends at 2:00 a.m. Sunday morning. Clocks “fall back” one hour. Daylight time for North America runs from the second Sunday in March to the first Sunday in November; the rules last changed in 2007. Daylight time is not used in Hawaii, Saskatchewan, Puerto Rico, or in most of Arizona.

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 3

■ The Summer Triangle Effect. Here it is early November, but Deneb still shines right near the zenith as the stars come out. And brighter Vega is still not far from the zenith, toward the west. The third star of the “Summer” Triangle, Altair, remains very high in the southwest. They seem to have stayed there for a couple months! Why have they stalled out?

What you’re seeing is a result of sunset and darkness arriving earlier and earlier during autumn. Which means if you go out and starwatch soon after dark, you’re doing it earlier and earlier by the clock. This counteracts the seasonal westward turning of the constellations.

Of course this “Summer Triangle effect” applies to the entire celestial sphere, not just the Summer Triangle. But the apparent stalling of that bright landmark inspired Sky & Telescope to give the effect that name many years ago, and it stuck.

Of course, as always in celestial mechanics, a deficit somewhere gets made up elsewhere. The opposite effect makes the seasonal advance of the constellations seem to speed up in early spring. The spring-sky landmarks of Virgo and Corvus seem to dash away westward from week to week almost before you know it, due to darkness falling later and later. Let’s call this the “Corvus effect.”

This Week’s Planet Roundup

Mercury remains very deep down in the sunset.

Venus, magnitude –4.0, gleams low in the southwest as evening twilight fades. It sets shortly after the end of twilight.

Mars (magnitude +0.2, in eastern Gemini) rises around 11 p.m. daylight-saving time. It shows best, very high in the south, in the hour or more before dawn. It’s about 36° east along the ecliptic from bright Jupiter. Mars in a telescope is still a small 9 arcseconds wide, on its way to a relatively distant opposition next January, when it will reach an apparent diameter of 14.5 arcseconds.

Jupiter (magnitude –2.7, still near the horntips of Taurus) rises in the east-northeast around 8 p.m. It’s highest toward the south through the early-morning hours. Jupiter is now a nice 46 arcseconds wide in a telescope, essentially as large as the 48-arcsecond width it will attain for the weeks around its opposition in December.

Mars here shows its North Polar Cap, dark Mare Sirenum near the South Polar Cloud Hood, and some finer detail. On Jupiter, the North Equatorial Belt (with a bright white cloud outbreak) is slightly darker than the South Equatorial Belt, at least on this side of the planet.

Saturn, magnitude +0.8 in Aquarius, is well up in the southeast as the stars come out. Don’t confuse it with Fomalhaut two fists to its lower right. Saturn is highest in the south by 9 p.m. daylight-saving time.

Uranus (magnitude 5.6, at the Taurus-Aries border) is well up by mid-evening about 6° from the Pleiades. You’ll need a good finder chart to identify it among its surrounding faint stars.

Neptune (tougher at magnitude 7.8, near the Circlet of Pisces) is already well up after nightfall, 15° east of Saturn. Again you’ll need a proper finder chart.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world’s mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions and graphics that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America.

Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is Universal Time minus 4 hours. Eastern Standard Time (EST) is UT minus 5 hours. UT is also known as UTC, GMT, or Z time.

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They’re the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For a more detailed constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you’ll need a much more detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas (in either the original or Jumbo Edition), which shows all stars to magnitude 7.6.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many. It’s currently out of print. The next up, once you know your way around well, are the even larger Interstellarum atlas (stars to magnitude 9.5) or Uranometria 2000.0 (stars to mag 9.75). And read How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope. It applies just as much to charts on your phone or tablet as to charts on paper.

You’ll also want a good deep-sky guidebook. A beloved old classic is the three-volume Burnham’s Celestial Handbook. An impressive more modern one is the big Night Sky Observer’s Guide set (2+ volumes) by Kepple and Sanner. The pinnacle for total astro-geeks is the Annals of the Deep Sky series, currently at 10 volumes as it slowly works forward through the constellations alphabetically. So far it’s only up to F.

Can computerized telescopes replace charts? Not for beginners I don’t think, and not for scopes on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically. Unless, that is, you prefer spending your time getting finicky technology to work rather than learning how to explore the sky. As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer’s Guide, “A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand and a curious mind.” Without these, “the sky never becomes a friendly place.”

If you do get a computerized scope, make sure that its drives can be disengaged so you can swing it around and point it readily by hand when you want to, rather than only slowly by the electric motors (which eat batteries).

However, finding faint telescopic objects the old-fashioned way with charts isn’t simple either. Learn the essential tricks at How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope.

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty’s monthly

podcast tour of the naked-eye heavens above. It’s free.

“The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It’s not that there’s something new in our way of thinking, it’s that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before.”

— Carl Sagan, 1996

“Facts are stubborn things.”

— John Adams, 1770