The other cop

Those not attuned to the world of environmental diplomacy can be forgiven for a certain confusion, not to mention fatigue, at the use of acronyms. And this is especially true when two different processes are commonly known by the same acronym. Monday 21st October saw the launch of COP16 in Cali, Colombia. Those who are aware, even vaguely, of climate change negotiations might be surprised by this, given that they probably heard talk of COP28 last year. This COP is the 16th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, and is focused on efforts to tackle the global biodiversity crisis. It is separate from Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC, which is focused on climate change and will this year be undergoing its 29th iteration (COP29) in Azerbaijan.

Taking stock of action on nature

Colombia ranks first globally for bird and orchid species diversity, and second for amphibians, freshwater fishes, butterflies, and plants. It is therefore a fitting setting for diplomatic talks on how to arrest the alarming loss of biodiversity the world has experienced in recent decades (since 1970, the size of animal populations for which we have data has declined by 73 per cent on average).

COP16 is the first gathering of its type since the adoption of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) at COP15 in 2022. Under this framework, countries agreed a range of ambitions, most striking of which was the target to reserve 30 per cent of land, water, and seas for nature by 2030. Ahead of this year’s summit, countries were supposed to deliver detailed plans, known as NBSAPs, for achieving these – although many have failed to meet this deadline. Using these plans, delegates will assess the extent to which 2022’s ambitious words are being translated into tangible action.

Biopiracy, funding, and indigenous involvement

In addition to this stock-taking exercise, several other items will be on the agenda in Cali. The genetic codes of the world’s organisms are an incredibly valuable commodity for those developing everything from cosmetics to medicines. And with the extraordinary statistical power of AI, the hunger for genetic information is only going to grow. But who will benefit? Many in developing countries fear that companies from the developed world will plunder their natural ecosystems to create lucrative products, giving local people little in return – a phenomenon known as ‘biopiracy.’ COP16 will see efforts to work out an agreed mechanism for paying for access to digitalised genetic data.

Another agenda item will be funding. A key question when it comes to biodiversity protection and restoration is a simple one: who pays? Many developing countries argue they need support to meet their targets, and, at COP15, governments agreed to pay up to the tune of at least $30 billion per year by 2030. However, access to finance is likely to remain a tense talking point at this year’s summit.

Finally, the involvement of indigenous peoples in biodiversity protection will be a further consideration, with host country Colombia pushing particularly hard for the involvement of indigenous communities.

Innovation’s role in protecting nature

COPs are, by definition, high level and couched in the language of policy and diplomacy. However, innovators around the world are playing essential roles in preserving biodiversity on the ground, far away from conference halls. At Springwise, we see three emerging trends for nature tech: monitoring and reporting, funding, and restoration. And the innovations we see in these areas bring the themes being discussed at COP16 to life in a tangible way.

Monitoring and reporting

To take action on biodiversity, decision-makers need to be able to monitor it at scale. And, increasingly, organisations are being required to report on their impact on the natural world. For example, one of the organisations that will be in Cali is The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD),a market-led initiative that has developed a set of disclosure recommendations and guidance that helps businesses report and act on their nature-related dependencies, impacts, risks, and opportunities. All this reporting data must ultimately be collected from the environment, and we are seeing three main techniques for doing this at scale: environmental DNA, acoustics, and satellite imagery.

The innovations

Photo credit: © nathalieburblis from pixabay via Canva.com

Monitoring biodiversity through bioacoustics

From birdsong to the chirping of crickets, the sounds of nature provide a familiar and often nostalgic backdrop to our lives. But they also contain valuable information about biodiversity via an emerging field called bioacoustics. One company working in this space is Bristol-based Carbon Rewild.

Founded in 2022, the startup leases recording equipment to organisations wishing to survey the biodiversity of a specific area. These sensors are kept in place for a period of one month, before being returned to Carbon Rewild, which then analyses the audio files for evidence of bird and bat calls. The customer then receives back a report of findings.

For decades, traditional methodologies such as direct visual observations and point counts have been the main means of assessing bird populations. However, they are susceptible to factors such as observer bias and the reactions of bird species to the presence of humans. Bioacoustics can supplement these older techniques by recording data passively in the background. Find out more

Photo credit: © qimono from pixabay via Canva.com

Biodiversity monitoring through eDNA

When it comes to assessing biodiversity, a key challenge is the fact that not every species is equally visible to human eyes. Some animals are secretive, elusive, or otherwise difficult to observe. However, all species leave signs of their presence in the form of environmental DNA – or eDNA – contained in organic matter that is shed by organisms, such as through faeces, mucus, or skin cells. When this material is recovered by scientists through sampling, it can provide insights into the species present in a given area.

French company SPYGEN provides eDNA analysis services using samples of water, soil, honey, or faeces. The analysis is conducted by experts brought together through the VigiDNA network, which was created by SPYGEN in 2016. By looking at eDNA, scientists can build up a much more detailed picture of the biodiversity of an ecosystem than would be possible through traditional methods. Find out more

Photo credit: © Lisa Fotios from Pexels via Canva.com

Analysing eDNA in soil

Soil microbes are fundamental to maintaining healthy ecosystems. They transform nutrients and make them accessible for plant uptake, while also supporting above-ground biodiversity and storing carbon. However, changing weather patterns are also causing changes in the diversity of the microbiome, threatening global systems. To maintain healthy soils, it is important to monitor them and identify any invasive species.

German startup Soilytix monitors and analyses soil biodiversity, including levels of bacteria, fungi, and microfauna. It then helps companies use this data to maximise crop yields and measure carbon removal potentials. For example, the company is working with supermarkets to enable them to accurately monitor the impact of regenerative practices used by farms within their supply chain. An AI-assisted soil sampling app allows clients to collect soil samples and send them to Soilytix’s lab for analysis. The company extracts the DNA of microorganisms in the sample and conducts DNA sequencing to identify and quantify any bacteria, fungi, and microfauna. Read more

Photo credit: © Tom Fisk from Pexels via Canva.com

AI and satellites: a new era for urban biodiversity analysis

UK startup Gentian uses high-resolution satellite imagery and AI analysis to scale and speed up land surveyance. The company’s technology enables urban planners, developers, and businesses to gather an ecological baseline for a particular location – something that is crucial to understanding biodiversity changes over time.

Rather than relying on on-the-ground analysis, which could vary depending on the method and tools being used, Gentian’s process eliminates uncertainties while mapping a much greater area of land in less time. The satellite imagery provides detail under 50 centimetres in resolution, often down to 30, 12, and five centimetres. And, in partnership with the European Space Agency, the company has also developed AI technology that recognises and quantifies vegetation based on habitat type.

In urban settings, this makes it possible for landowners and governments to track the biodiversity net gains of sustainability measures such as green roofs, tree planting, and micro parks. For more remote and larger areas, Gentian’s aerial analysis helps ecologists and other researchers monitor land use more quickly and cost-efficiently, making it easier to identify illegal activity and prevent substantial environmental damage. Read more

Funding

According to the OECD, biodiversity finance from across the public and private sectors today totals $78-91 billion per year. However, the organisation argues that finance actually needs to be in the hundreds of billions of dollars annually if we are to avoid significant risks and costs to human health, well-being, and the economy. Public funding is crucial to plugging this gap, but so too is funding from the private sector, and a range of innovators are working to facilitate this.

The innovations

© Khwanchai Phanthong’s Images via Canva.com

Turning natural capital into an investable asset

According to the World Economic Forum, half of the world’s GDP is moderately or highly dependent on nature and its services. Natural capital is an emerging asset class that aims to reflect this fact by giving value to the natural world. Now, US startup Cultivo is using data and proprietary algorithms to create a ‘search engine’ for natural capital across the globe.

This technology platform enables Cultivo to assess, at scale, how the world’s lands have been degraded. The company can then assess the potential natural capital returns of restoration work on a given plot of land, including improvements in soil moisture and carbon sequestration capacity. Working with local NGOs and landowners, Cultivo packages the most promising projects into tailored investment portfolios, which are then sold to fund the activities that restore and protect nature. In return, investors receive cashflows through carbon offset sales and other ecosystem services.

On the ground, projects are delivered in close cooperation with local communities and the claimed improvements in natural capital are audited by third parties via expert analysis, sensors, and satellite images. Find out more

Photo credit: Amazonian Impact Ventures

Sustainability-linked loans for indigenous forest peoples

Amazonia Impact Ventures (AIV) has developed a blended finance approach that links indigenous peoples, investors, and businesses buying from the Amazon. The company uses investment funds to offer loans to indigenous businesses that are structured around agreed sustainability targets. In addition to funding, AIV offers support to develop regenerative farming practices and sustainable land use, while also helping to improve marketing and product range.

Buyers benefit from access to high-quality, deforestation-free commodities, and the Amazon bio-economy benefits from the strengthening of value chains of non-timber forest products such as wild berries, fruits, nuts, and native crops. AIV co-founder, Pajani Singah, has said that the organisation hopes to demonstrate “that if capital flows are deployed correctly, it can have an immense impact on the communities, nature, and the forest’s economy.” Read more

Photo credit: © Tom Fisk via Canva.com

Providing indigenous communities with funding for forest stewardship

One Tribe puts indigenous people back in the driving seat of rainforest protection by providing native communities and smallholders with funding for their stewardship and protection of forests through nature-based offsets and removal. The company specialises in connecting forestry protection projects, indigenous tribal land, and rainforest organisations directly to global payment systems. This enables businesses to provide a portion of every sale or transaction to global carbon sequestration projects. After a purchase is made on a One Tribe partner store, the company makes a donation to its connected rainforest protection charities on the buyer’s behalf.

One Tribe’s partner charities ensure the land is protected in various ways: by creating land titles for indigenous peoples so that they have legal ownership over an area, by turning land into National Parks or areas of official protection, and by purchasing the land directly. Through the offsets, businesses can fund biodiversity protection as part of their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) campaigns. One Tribe directs funds only to high-grade verified carbon offset and conservation-focused projects, certified by industry-leading standards. Read more

Restoration

One of the targets within the GBF is for countries to have completed or initiated restoration activities on at least 30 per cent of degraded ecosystems by 2030. And the European Commission estimates that every €1 spent on nature restoration returns between €8 and €38 through improved climate mitigation and adaptation, food security, and human health and well-being. Innovators around the world are therefore deploying the latest technologies to restore nature on a large scale.

The innovations

Photo credit: Arkadiah

Reviving nature: a new era of tech-driven restoration

Often, nature restoration projects are met with long and cumbersome processes, which hinders fundraising, scaling, and speed. Now, startup Arkadiah Technology has developed a solution to bring traceability and transparency to these projects, making it easier to unlock financing and scale land restoration. The company has built a platform designed especially for climate mitigation projects in Southeast Asia, a region that saw greenhouse gas emissions rise faster than anywhere else in the world between 1990 and 2010.

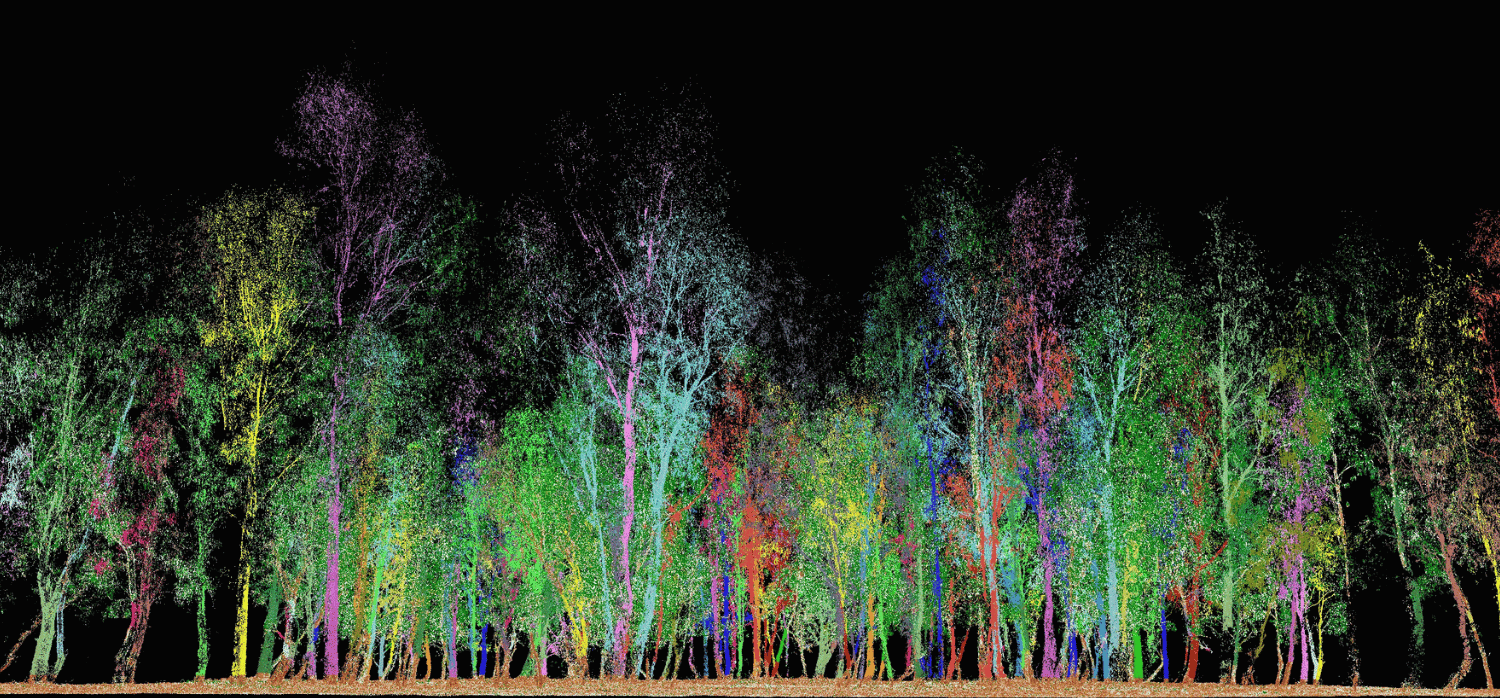

Arkadiah’s approach uses AI, LiDAR, satellite imagery, and ground truthing to provide transparent and verifiable data. Project developers, landowners, and corporations can then use this information to streamline the deployment of nature-based climate solutions, such as reforestation projects, and quickly issue quality carbon removal and biodiversity credits. Read more

Photo credit: Rhizocore

Restoring fungal networks to improve tree-planting

From 2001 to 2022, the UK lost around 541 kilohectares of trees, equating to a 15 per cent decrease in tree cover across the country. There are increasing efforts to replant in previously forested areas, however, many of the saplings that are planted will never make it to adulthood, especially if they are planted in clear-felled areas or ex-agricultural sites. One reason for this is the fact that the saplings lack a mycorrhizal support network. The mycorrhizal support network, dubbed the ‘woodwide web,’ is a network of fungi in the soil. It is thought to be essential to the growth of healthy forests as it allows trees to share water, nitrogen, carbon, and other minerals, maximising growth.

Startup Rhizocore Technologies is working to give saplings a healthier head start by restoring underground fungal networks to accelerate woodland regeneration. Rhizocore grows ectomycorrhizal fungi, which form advanced symbiotic associations with trees in the beech, pine, willow, and lime tree families. The startup turns the fungi into pellets, which can be planted along with saplings, using the same process. The fungi then grow and connect the saplings into a web. Read more

Photo credit: Carnegie Mellon University

Self-drilling wooden seed carriers for reforestation projects

Researchers led by Professor Lining Yao at the Morphing Matter Lab in the Human-Computer Interaction Institute at Carnegie Mellon University have created a bioengineered seed carrier called an E-seed that pushes seeds and fertiliser deep into the ground. Activated by water, the carriers are made from veneers of white oak. The wood is washed in sodium sulphite and sodium hydroxide for strength and durability, and then mechanically moulded into a twisted shape with three tails at one end. After loading the materials to be planted into the carrier, the tip is coated and flocked.

The carriers are strong enough to carry large seeds, fertilisers, fungi, and a range of other materials. When activated by water, the wood expands and untwists, driving the seed tip down. The carriers are delivered by drones and have the potential to reforest large geographic and inhospitable regions, or to restore wetlands that are difficult for humans to traverse. Read more

As a member, you have unlimited access to our library of over 14,000 innovation case studies. If this feature has piqued your interest, why not have a deeper dive into biodiversity today?