A review of a new book released this week:

What makes modern and contemporary Japanese houses so appealing? Much of it stems from the novelty of residential designs, which can be traced to a litany of factors, including a cultural acceptance of demolition and renewal that creates a constant stream of new architecture; a litany of legal requirements pushing architects — both young and established — to be formally creative; and let’s not leave out the clients willing to take risks. Most of the houses that spark jealousy in architects outside of Japan are found in Tokyo and other urban areas where money, zoning, and architects converge to fuel unexpected creations. One factor, the country’s exorbitant inheritance tax, leads many families to cut up their properties into smaller parcels to pay for the tax; the resulting, awkward pieces of land then require architects to squeeze a house into a wrapper defined by fire-safety requirements, sunshine laws, and practical concerns like a parking space. Such is the case today, but distinctive single-family houses in and beyond Tokyo have been prevalent since the end of World War II, when architects took part in the necessary postwar rebuilding that was buoyed by prosperity in the ensuing decades. Naomi Pollock’s excellent The Japanese House Since 1945 traces the evolution of single-family houses across eight decades, focusing as much on the people who live(d) in the houses than the architects who designed them.

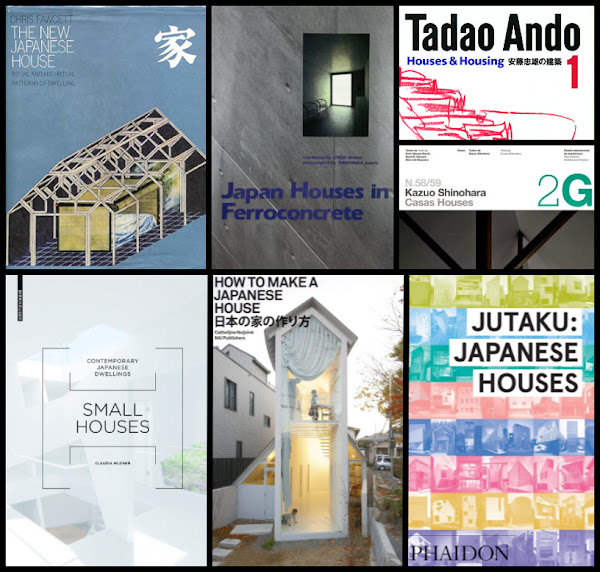

The book is structured as a chronological, decade-by-decade presentation of nearly one hundred houses across 400 pages. Each house is documented in two to five pages with photographs, drawings, and a brief description. The photographs are of their period, rather than contemporary, probably done because most of the old houses have long been demolished. The floor plans are also original, rather than redrawn for the book, but they use a helpful numbered key that is consistent across the book. Last, and perhaps most important, are Pollock’s descriptions, which incorporate quotes from the architects and/or the owners and provide details on the designs and living situations beyond typical surveys. Pollock has written numerous books on Japanese architecture, is an international correspondent for Architectural Record, and has elsewhere brought her firsthand accounts and access to architects in Japan to bear on architecture that many people outside of Japan are fascinated by. Compared to books such as New Architecture in Japan, co-written with Yuki Sumner, and Jutaku: Japanese Houses (see bottom of this review),

The Japanese House Since 1945 is her most important and best book to date.

Although the Japanese houses that are the subject of Pollock’s new book are billed as, per the back cover, “many of the most exceptional and experimental houses in the world,” it starts with houses that are more traditional than modern.

Kunio Maekawa’s own house in Tokyo, completed in 1942, has a wood exterior that “evoked traditional Japanese farmhouses,” Pollock writes, but has a “spacious living room, exemplifying Maekawa’s vision of the ideal house for the burgeoning modern era.” Maekawa worked in the Paris atelier of Le Corbusier, later joining Antonin and Noémi Raymond in Tokyo, two foreign architects who moved to Japan after World War I (Antonin worked with Frank Lloyd Wright on the Imperial Hotel). The couple left Japan ahead of WWII but returned after its conclusion, building a house and studio (above spread) in Tokyo that is also rooted in traditional Japanese architecture but subtly signals this “burgeoning modern era.” These two instances illustrate how outside influences entered Japan after the war, with tradition and modernity mixing in ways that would eventually lead to the exceptional architectural experimentation the country is known for.

The chronological, decade-by-decade presentation allows the evolution of Japanese residential architecture to unfold gradually and be seen in the context of the 1964 Olympics, Expo 1970 in Osaka, the end of the bubble era, the March 2011 earthquake, COVID-19, and other epoch-defining events that are described by Pollock in intros to each decade. Readers see the introduction of concrete, steel, and other materials in the 1960s and 70s, followed by the light construction of the 80s and 90s, and the formal experimentation of our current century. Each decade has at least one icon — Kiyonori Kikutake’s Sky House in the 50s, Kazuo Shinohara’s Umbrella House in the 60s, Tadao Ando’s Row House in Sumiyoshi in the 70s, etc. — but most readers will find something new among the 98 houses. Even those well-versed in modern Japanese houses will be pleased by the nine “At Home” pieces inserted throughout the book. In these, we learn about Yuki Kikutake, daughter of Kiyonori, growing up in Sky House; Fumihiko Maki writes about his own house built in Tokyo in 1978; and we read about the anonymous husband and wife living in Sou Fujimoto’s House NA. A last ingredient is nine spotlights — one at the end of each chapter — that discuss the articulation of various elements: roofs, windows, stairs and corridors, gardens and courtyards, etc. The brief case studies, “At Home” features, and spotlights combine to create a compelling and vivid portrait of modern living in Japan over the last eight decades.

Naomi Pollock’s latest book prompted me to dig out a few other titles from my library that also present Japanese houses. They are described briefly below, presented in chronological order by date of publication, and are intended for anyone who wants do delve deeper into some of the decades or architects explored in Pollock’s book; titles with links point to earlier reviews on this blog. Readers who want a more comprehensive overview of early modern Japanese architecture (not just houses) should find David B. Stewart’s The Making of a Modern Japanese Architecture rewarding.

The New Japanese House: Ritual and Anti-Ritual, Patterns of Dwelling by Chris Fawcett, published by Harper & Row, 1980 (Amazon / AbeBooks)

The push and pull between tradition and modernity is the subject of this book by Chris Fawcett, the British critic who wanted to undo misconceptions in the West about Japanese houses. He focused on “Post-Metabolist” architecture, houses from the late 1960s and the 1970s that he presented as “ritual affirming” and “ritual disaffirming” houses. It’s an intriguing book, but not one that seems to have had much of an influence all these years later; I wonder if Fawcett would have gone on to make more lasting and impactful books on Japanese architecture if he didn’t die young. The New Japanese House can be bought inexpensively online, but harder to find is GA Houses 4: Ontology of House, Residential Architecture of 1970s in Japan, which features an essay by Fawcett and dozens of houses from that decade.

Japan Houses in Ferroconcrete by Makoto Uyeda, photography by Junichi Shimomura, published by Graphic-Sha, 1988 (Amazon / AbeBooks)

This book features 35 houses designed by 21 architects, all united by the use of concrete, varying from small applications, such as alongside wood, steel, and other materials, to expansive houses in reinforced concrete by the likes of Tadao Ando. Although dates are not provided for the houses, most are from the 1980s with some from the previous decade. One of the most rewarding aspects of this book, which I was chuffed to discover while browsing a used bookstore, is the fact all of the photographs — and there are A LOT of them — were specially taken for the book; they go much deeper inside the houses than the “official” photographs found in monographs and other publications.

One thing I find appealing about architecture in Japan is the way many famous architects there continue to design single-family houses even after getting hired for museums, office buildings, and other larger projects; houses are not merely a leg up to bigger commissions. In turn, monographs on architects’ houses can occasionally be found. A couple favorites of mine are the first book in Toto’s now-five-strong series on Tadao Ando (Houses and Housing was followed by Outside Japan,

Inside Japan,

New Endeavors, and

Dialogues) and a double issue of 2G devoted to the houses of Kazuo Shinohara built between 1959 and 1988. In addition to them including some of the best modern Japanese houses ever built, the two publications are beautifully produced.

Another appealing aspect of Japanese houses is their size. Even though the petit houses prevalent in Japan can be attributed to the country’s population density, the breaking up parcels to pay for inheritance taxes, as mentioned above, and other considerations that aren’t necessarily geared to the sustainability of living small, it’s refreshing to see so much creativity put into small houses rather than the oversized houses that are the norm in the US. This appropriately small book is a good collection of around two-dozen small houses by Go Hasegawa, Atelier Bow-Wow, Sou Fujimoto, and others, all of them completed within the few years leading up to the book’s publication. The years since have seen many more creative Japanese houses but fewer house books for readers outside of Japan; websites are now the norm, but I’d be more than happy with more books like Small Houses.

Astute readers may have noticed that most of the books featured in this post were authored by foreigners (Pollock from the US, Fawcett from the UK, Hildner from Germany, Nuijsink from The Netherlands), which goes hand in hand with the strong appeal Japanese houses have on people outside of Japan. I can’t imagine a book titled “How to Make a Japanese House” coming from a Japanese architect; they would not need to explain the work they do on a daily basis to fellow Japanese architects doing the same. For Cathelijne Nuijsink, the premise of the book allowed her to explore the making of Japanese houses through in-depth interviews with four generations of their creators: Jun Aoki, Kazuyo Sejima, Junya Ishigami, and so on. It’s an excellent book that remains in print a decade later.

Jutaku: Japanese Houses by Naomi Pollock, published by Phaidon, 2015 (Amazon / Bookshop)

Appropriately, this review of Naomi Pollock’s The Japanese House Since 1945 ends with another book by Pollock: a compact Phaidon picture book with more than 400 contemporary Japanese houses, from Hokkaido in the snowy north to Kyushu in the subtropical south. Not surprisingly, most of the houses are found in Kanto Prefecture, which is anchored by Tokyo. It’s a stellar collection that suffers from too much in a small package: there is only one photo per house, an exterior photo that shows readers what anyone would be able to see in public, just hinting at the qualities within. Two photos per house — one outside, one inside — could have been done with a slightly larger paper size. Alas, the book proves the creativity in Japanese residential architecture but leaves us wanting more — much more.