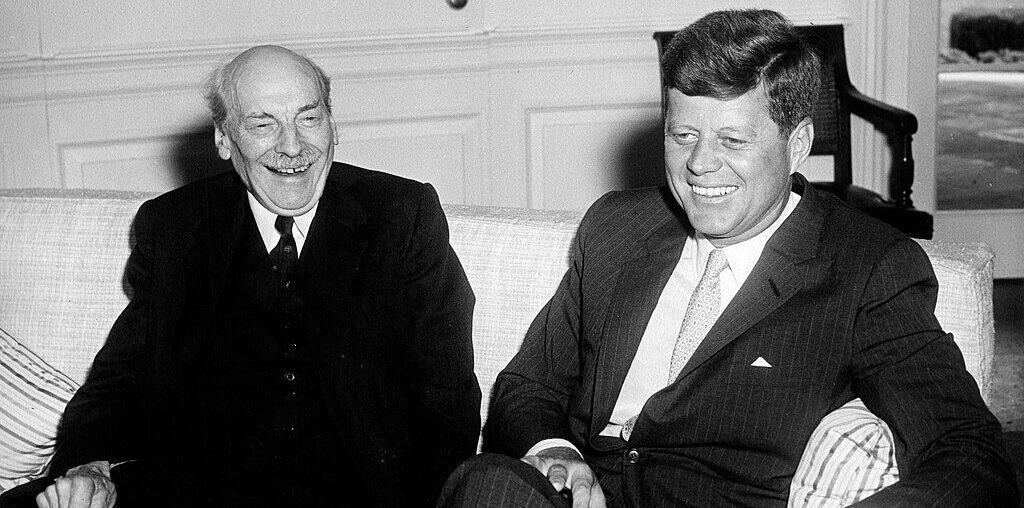

Clement Attlee with John F. Kennedy in 1961.

The UK General Election held in July 2024 was a truly historic event, with Labour returning to office after more than a decade in opposition. The fact that Labour did so with such a massive majority means that they have a strong mandate to transform Britain into a fairer nation. Although the state of public finances has resulted in Labour removing universal Winter Fuel Allowances for most pensioners (ironically reversing a policy implemented under the Blair Government in 1997) and more cuts likely to follow, it is highly probable that as economic conditions improve there will be greater leeway for Labour to expand social provisions, such as fulfilling its proposals for extending rights to statutory sick pay and introducing free breakfast clubs in all English primary schools. In the past, Labour has encountered severe financial difficulties but has still managed to establish a broad array of social security grants that have done much to ameliorate the quality of life for ordinary households. Two former Labour administrations that Starmer and his ministers can look to for guidance are the Attlee Government of 1945-51 and the 1964-70 and 1974-76 Wilson Governments.

Attlee Government

The Labour Government that came to power in the first election following the end of the Second World War has long been held in high esteem not only by historians but also by Labour Party activists and politicians. Led by veteran Labourite Clement Attlee, it was by far the most radical and successful that Britain had experienced by that time. Although the country Labour inherited was in a parlous financial state (the legacy of World War II), Attlee and his ministers would not disappoint an electorate hungry for change after years of strife and sacrifice. Over the next 6 years, they drastically changed Britain for the better. One way it achieved this was through the construction of a comprehensive and universalistic welfare model. Although Britain had a long history of welfare provision, the Attlee Government greatly built on the existing framework by setting up a system that covered all citizens. One of the pillars of this new solidaristic edifice, the National Health Service, was notable in making free access to every form of healthcare (such as medical and dental care, eyeglasses and hearing aids) a right for every citizen; one that the service has continued to uphold despite frequent cuts and overhauls in the decades since its “birth.” The 1946 National Insurance Act set up a broad network of cash payments incorporating a range of risks such as old age, widowhood and funeral costs. Apart from the normal rates, increases could be made in national insurance paymentsfor particular cases. Also, where employers had failed to meet the contribution requirements of the Act, resulting in recipients losing partly or entirely the maternity, sickness or unemployment benefits that were theirs by right, such individuals could retrieve a civil debt from said employers representing the lost amounts. A Five Year Benefit Reviewwas also included, aimed at ensuring the adequacy of allowances in helping beneficiaries to meet their basic needs. Additionally, groups such as trade unions were enabled to set up their own schemes if they so wished.

The equally far-reaching Industrial Injuries Act passed that same year bestowed various cash grants upon workers suffering from work-related injuries such as disablement gratuities and special hardship allowances (aimed at workers unable to carry out their current lines of work or equivalent due to their injuries). Five distinct benefits were also made for dependents of workers who tragically lost their lives, while allowances were given in cases of approved hospital treatment, constant attendance and unemployability; the latter geared towards disability pensioners unable to take on any form of employment. In addition, the National Assistance Act introduced two years later established a non-contributory social safety net for those in need; providing support such as shelter and nutritional assistance.

The Attlee years also witnessed the passage of other welfare measures affecting different strata of British society.Dockworkers became entitled to pay in cases of unemployment or underemployment, while a state scheme for mature university students was set up. Regulations provided numerous pension entitlements for NHS employees while the National Insurance and Civil Service (Superannuation) Rules, 1948 provided for preserved pension rights with a compensation award in cases where individuals experienced the impairment or loss of opportunity to earn a further pension. As a means of helping people reach their potential, a special scheme was instituted in 1947 whereby individuals with a gift for skilled crafts became eligible for grants to undertake training in other locations if no suitable facilities existed near where they lived.

In 1946, certain pensioners with disabilities that added to wear and tear became entitled to a new clothing allowance, while a couple of years later greater eligibility for special education allowances for children was introduced. The 1948 Local Government Act generalised various powers to pay subsistence and travelling allowances to members of local authorities while also providing payments in cases where council business attendance led to financial loss. The 1947 Agriculture Act incorporated several forms of compensation, such as for disturbance and improvement, while the 1948 Criminal Justice Act provided for the enforcement of payments of compensation or damages. Under the 1948 Children Act, local authorities were empowered to care for children who were orphaned, deserted or unable to be looked after by their parents due to circumstance. Amongst its many provisions included accommodation for children reaching 3 years of age, along with grants for students to help them with the costs of maintenance, training or education. A year later, a system of legal assistance was inaugurated that entitled most people to free legal support in both civil and criminal cases.

Impact of the Attlee Government

The extent to which the social security legislation of the Attlee Government dramatically improved people’s lives can be gauged from a poverty study conducted in York in 1950 by the legendary researcher and humanitarian Seebohm Rowntree; using that location as a representative sample. A follow up to a previous survey carried out in the same area in 1936, it estimated that the percentage of working-class people in York who lived in poverty stood at 2.77% in 1950, compared with 31.1% 14 years earlier. Although the study undoubtedly overestimated the extent to which poverty fell during that period, it nevertheless highlights the fact that the Welfare State established under Attlee did much to diminish the numbers experiencing hardship. G.R. Lavers, who co-authored the report, argued that the largest improvement since 1936 had come about as a result of the welfare reforms instituted since 1945, going as far as to claim that the Welfare State had greatly overcome poverty. This assertion gave Labour a positive message to convey to the public during the 1951 election campaign, but despite their efforts would be voted out of office; not returning to power until 1964 under the leadership of former minister Harold Wilson.

Wilson Governments

Like Attlee’s Administration, Harold Wilson and his ministers inherited a nation in a difficult economic position; one that eventually resulted in the currency being devalued. This culminated in detestable austerity policies including higher charges for school meals. Also, In a dubious move, one that undoubtedly reflected exaggerated perceptions of welfare fraud that persist to this day, a “four-week rule” was instituted in July 1968 in certain places. This involved social assistance benefits being removed from recipients after this time if it was believed that there was suitable work available. Assessing the impact of this measure, one study edited by the anti-poverty activist and future cabinet minister Frank Field provided the estimate that 10% of those affected by the rule subsequently ventured into crime as a consequence of their losing their benefits. Despite a ministerial claim that this policy had been a success in tackling benefit fraud, Field’s study suggests that it was a misguided decision that caused unnecessary hardship.

Nevertheless, for most of its period in office Labour not only boosted public spending but also rolled out a programme of radical welfare reform that did much to lessen inequality. New benefits were introduced concerning risks that previously had been left uncovered by the Attlee welfare laws. Redundancy pay was set up, along with income supplements for beneficiaries such as unwell, injured and jobless persons; the latter to lessen the impact of unemployment for skilled employees. New allowances for partially incapacitated men were also established, with increased amounts were permitted in certain cases.

The 1965 Solicitors Act allowed for grants to be paid in hardship situations, while other laws introduced varying forms of compensation for those affected by compulsory land purchases and damage. National Assistance was superseded by a new Supplementary Benefits Scheme; an overhaul carried out partly to prevent detailed individual enquiries. Reflecting this philosophical shift, changes were made, for instance, to rent allowance payments for non-householders (previously, these had been dependent upon a household’s make-up). Although not without its faults, it was a definite improvement over the previous social assistance arrangements. Higher benefit rates were provided and, although the allowances under the new scheme were mostly the same as under National Assistance (with exceptions such as an additional allowance for long-term claimants), what differed was the fact that the new scheme sought to ensure that benefits would be given as a right to those who met the means-tested conditions, while seniors were entitled to an income guarantee. Measures were also carried out with the intention of enabling widows and women whose marriages had dissolved to receive higher pensions, while regulations established improved levels of financial assistance for disabled people (such as an allowance for severe disabilities), and allowed for Christmas bonuses to be disregarded in the estimation or calculation of earnings when determining national insurance payments. Local tax rebates were created to assist less well-off ratepayers, and the 1965 Matrimonial Causes Act was designed to helpwomen by means of ordering alimony and other forms of payment to the concerned parties. Additionally, measures were undertaken to tackle homelessness and deliver residential services to persons who are ill and living with disabilities.

The social security record of Wilson’s first administration can be justified by the impact its policies had on those living on low incomes. In 1970, the amount that benefits and taxes added to the incomes of those earning £315 annually was more than twice the equivalent amount from 1964. Measurements have also suggested that the number of individuals living in poverty was far lower in 1970 than in 1964; further justification of Labour’s welfare record from the Sixties. One such benchmark, utilising a 1970-based absolute poverty line, has suggested that the percentage of poor Britons fell from around 20% to around 15% by the end of Wilson’s first premiership. Wilson’s last government from 1974 to 1976 would also see further landmarks in social security, with various laws passed that established new entitlements including invalidity pensions and mobility and invalidity care allowances for the disabled, earnings-related pensions, and Child Benefit; a universal payment which for the first time included financial support to families with at least one child and enhanced the amount of assistance allocated to low-income families.

The administrations in context

In a way, both administrations reflected the spirit of the times that they governed in. In the decade or so following the end of the hostilities, several war-torn nations in Europe came under the leadership of left-wing coalitions that expanded their social aid systems, while even poorer nations led by progressives including Burma (Myanmar), Guatemala, Iran and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) undertook reforms in this field. Similarly, during Wilson’s first stint as prime minister several developing nations led by reformers throughout the Sixties like India, Turkey, Honduras and the Philippines also embarked upon their own programmes of welfare innovation. The revolutionary social security reforms implemented under Attlee and Wilson therefore reflected broader geopolitical trends during their incumbencies.

The record of the Attlee and Wilson administrations shows that even under dire economic circumstances there is much that can be achieved in strengthening the social security structure that has done much throughout the decades to prevent and mitigate poverty in the United Kingdom. Like their forebears, the Starmer Government must never lose sight of Labour’s goal to make Britain a nation free of injustice. A more generous welfare system is a prerequisite to this. Although it is likely that it will take time until the financial situation improves to the point that Labour will be able to pursue looser, more expansionary fiscal measures to attain its reformist vision, the Starmer Government must nevertheless reinforce the Welfare State as an effective tool against the scourges of poverty, as most Labour governments have done so in the past. The welfare records of the Attlee and Wilson ministries are ones that the new Labour administration can learn greatly from today.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.