By: Hechao Li and Marcelo Mayworm

With special thanks to our stunning colleagues Amer Ather, Itay Dafna, Luca Pozzi, Matheus Leão, and Ye Ji.

At Netflix, the Analytics and Developer Experience organization, part of the Data Platform, offers a product called Workbench. Workbench is a remote development workspace based on Titus that allows data practitioners to work with big data and machine learning use cases at scale. A common use case for Workbench is running JupyterLab Notebooks.

Recently, several users reported that their JupyterLab UI becomes slow and unresponsive when running certain notebooks. This document details the intriguing process of debugging this issue, all the way from the UI down to the Linux kernel.

Machine Learning engineer Luca Pozzi reported to our Data Platform team that their JupyterLab UI on their workbench becomes slow and unresponsive when running some of their Notebooks. Restarting the ipykernel process, which runs the Notebook, might temporarily alleviate the problem, but the frustration persists as more notebooks are run.

While we observed the issue firsthand, the term “UI being slow” is subjective and difficult to measure. To investigate this issue, we needed a quantitative analysis of the slowness.

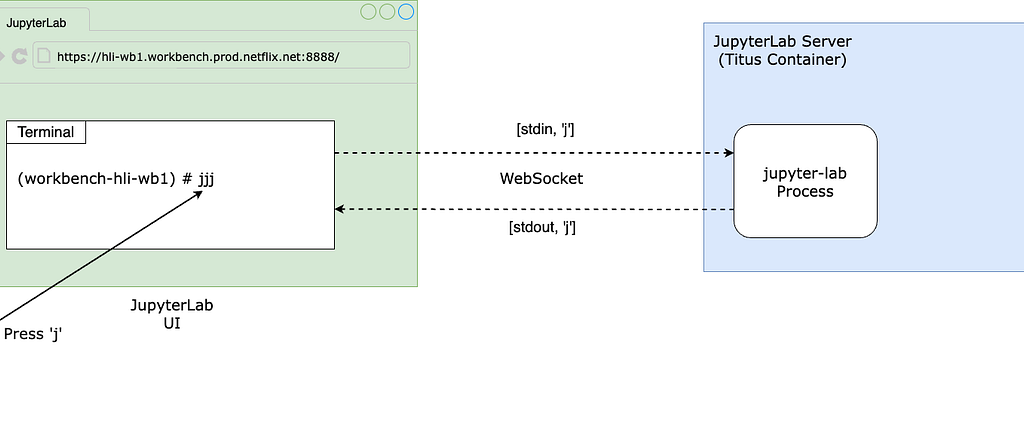

Itay Dafna devised an effective and simple method to quantify the UI slowness. Specifically, we opened a terminal via JupyterLab and held down a key (e.g., “j”) for 15 seconds while running the user’s notebook. The input to stdin is sent to the backend (i.e., JupyterLab) via a WebSocket, and the output to stdout is sent back from the backend and displayed on the UI. We then exported the .har file recording all communications from the browser and loaded it into a Notebook for analysis.

Using this approach, we observed latencies ranging from 1 to 10 seconds, averaging 7.4 seconds.

Now that we have an objective metric for the slowness, let’s officially start our investigation. If you have read the symptom carefully, you must have noticed that the slowness only occurs when the user runs certain notebooks but not others.

Therefore, the first step is scrutinizing the specific Notebook experiencing the issue. Why does the UI always slow down after running this particular Notebook? Naturally, you would think that there must be something wrong with the code running in it.

Upon closely examining the user’s Notebook, we noticed a library called pystan , which provides Python bindings to a native C++ library called stan, looked suspicious. Specifically, pystan uses asyncio. However, because there is already an existing asyncio event loop running in the Notebook process and asyncio cannot be nested by design, in order for pystan to work, the authors of pystan recommend injecting pystan into the existing event loop by using a package called nest_asyncio, a library that became unmaintained because the author unfortunately passed away.

Given this seemingly hacky usage, we naturally suspected that the events injected by pystan into the event loop were blocking the handling of the WebSocket messages used to communicate with the JupyterLab UI. This reasoning sounds very plausible. However, the user claimed that there were cases when a Notebook not using pystan runs, the UI also became slow.

Moreover, after several rounds of discussion with ChatGPT, we learned more about the architecture and realized that, in theory, the usage of pystan and nest_asyncio should not cause the slowness in handling the UI WebSocket for the following reasons:

Even though pystan uses nest_asyncio to inject itself into the main event loop, the Notebook runs on a child process (i.e., the ipykernel process) of the jupyter-lab server process, which means the main event loop being injected by pystan is that of the ipykernel process, not the jupyter-server process. Therefore, even if pystan blocks the event loop, it shouldn’t impact the jupyter-lab main event loop that is used for UI websocket communication. See the diagram below:

In other words, pystan events are injected to the event loop B in this diagram instead of event loop A. So, it shouldn’t block the UI WebSocket events.

You might also think that because event loop A handles both the WebSocket events from the UI and the ZeroMQ socket events from the ipykernel process, a high volume of ZeroMQ events generated by the notebook could block the WebSocket. However, when we captured packets on the ZeroMQ socket while reproducing the issue, we didn’t observe heavy traffic on this socket that could cause such blocking.

A stronger piece of evidence to rule out pystan was that we were ultimately able to reproduce the issue even without it, which I’ll dive into later.

The Workbench instance runs as a Titus container. To efficiently utilize our compute resources, Titus employs a CPU oversubscription feature, meaning the combined virtual CPUs allocated to containers exceed the number of available physical CPUs on a Titus agent. If a container is unfortunate enough to be scheduled alongside other “noisy” containers — those that consume a lot of CPU resources — it could suffer from CPU deficiency.

However, after examining the CPU utilization of neighboring containers on the same Titus agent as the Workbench instance, as well as the overall CPU utilization of the Titus agent, we quickly ruled out this hypothesis. Using the top command on the Workbench, we observed that when running the Notebook, the Workbench instance uses only 4 out of the 64 CPUs allocated to it. Simply put, this workload is not CPU-bound.

The next theory was that the network between the web browser UI (on the laptop) and the JupyterLab server was slow. To investigate, we captured all the packets between the laptop and the server while running the Notebook and continuously pressing ‘j’ in the terminal.

When the UI experienced delays, we observed a 5-second pause in packet transmission from server port 8888 to the laptop. Meanwhile, traffic from other ports, such as port 22 for SSH, remained unaffected. This led us to conclude that the pause was caused by the application running on port 8888 (i.e., the JupyterLab process) rather than the network.

As previously mentioned, another strong piece of evidence proving the innocence of pystan was that we could reproduce the issue without it. By gradually stripping down the “bad” Notebook, we eventually arrived at a minimal snippet of code that reproduces the issue without any third-party dependencies or complex logic:

import time

import os

from multiprocessing import ProcessN = os.cpu_count()

def launch_worker(worker_id):

time.sleep(60)

if __name__ == '__main__':

with open('/root/2GB_file', 'r') as file:

data = file.read()

processes = []

for i in range(N):

p = Process(target=launch_worker, args=(i,))

processes.append(p)

p.start()

for p in processes:

p.join()

The code does only two things:

- Read a 2GB file into memory (the Workbench instance has 480G memory in total so this memory usage is almost negligible).

- Start N processes where N is the number of CPUs. The N processes do nothing but sleep.

There is no doubt that this is the most silly piece of code I’ve ever written. It is neither CPU bound nor memory bound. Yet it can cause the JupyterLab UI to stall for as many as 10 seconds!

There are a couple of interesting observations that raise several questions:

- We noticed that both steps are required in order to reproduce the issue. If you don’t read the 2GB file (that is not even used!), the issue is not reproducible. Why using 2GB out of 480GB memory could impact the performance?

- When the UI delay occurs, the jupyter-lab process CPU utilization spikes to 100%, hinting at contention on the single-threaded event loop in this process (event loop A in the diagram before). What does the jupyter-lab process need the CPU for, given that it is not the process that runs the Notebook?

- The code runs in a Notebook, which means it runs in the ipykernel process, that is a child process of the jupyter-lab process. How can anything that happens in a child process cause the parent process to have CPU contention?

- The workbench has 64CPUs. But when we printed os.cpu_count(), the output was 96. That means the code starts more processes than the number of CPUs. Why is that?

Let’s answer the last question first. In fact, if you run lscpu and nproc commands inside a Titus container, you will also see different results — the former gives you 96, which is the number of physical CPUs on the Titus agent, whereas the latter gives you 64, which is the number of virtual CPUs allocated to the container. This discrepancy is due to the lack of a “CPU namespace” in the Linux kernel, causing the number of physical CPUs to be leaked to the container when calling certain functions to get the CPU count. The assumption here is that Python os.cpu_count() uses the same function as the lscpu command, causing it to get the CPU count of the host instead of the container. Python 3.13 has a new call that can be used to get the accurate CPU count, but it’s not GA’ed yet.

It will be proven later that this inaccurate number of CPUs can be a contributing factor to the slowness.

Next, we used py-spy to do a profiling of the jupyter-lab process. Note that we profiled the parent jupyter-lab process, not the ipykernel child process that runs the reproduction code. The profiling result is as follows:

As one can see, a lot of CPU time (89%!!) is spent on a function called __parse_smaps_rollup. In comparison, the terminal handler used only 0.47% CPU time. From the stack trace, we see that this function is inside the event loop A, so it can definitely cause the UI WebSocket events to be delayed.

The stack trace also shows that this function is ultimately called by a function used by a Jupyter lab extension called jupyter_resource_usage. We then disabled this extension and restarted the jupyter-lab process. As you may have guessed, we could no longer reproduce the slowness!

But our puzzle is not solved yet. Why does this extension cause the UI to slow down? Let’s keep digging.

From the name of the extension and the names of the other functions it calls, we can infer that this extension is used to get resources such as CPU and memory usage information. Examining the code, we see that this function call stack is triggered when an API endpoint /metrics/v1 is called from the UI. The UI apparently calls this function periodically, according to the network traffic tab in Chrome’s Developer Tools.

Now let’s look at the implementation starting from the call get(jupter_resource_usage/api.py:42) . The full code is here and the key lines are shown below:

cur_process = psutil.Process()

all_processes = [cur_process] + cur_process.children(recursive=True)for p in all_processes:

info = p.memory_full_info()

Basically, it gets all children processes of the jupyter-lab process recursively, including both the ipykernel Notebook process and all processes created by the Notebook. Obviously, the cost of this function is linear to the number of all children processes. In the reproduction code, we create 96 processes. So here we will have at least 96 (sleep processes) + 1 (ipykernel process) + 1 (jupyter-lab process) = 98 processes when it should actually be 64 (allocated CPUs) + 1 (ipykernel process) + 1 (jupyter-lab process) = 66 processes, because the number of CPUs allocated to the container is, in fact, 64.

This is truly ironic. The more CPUs we have, the slower we are!

At this point, we have answered one question: Why does starting many grandchildren processes in the child process cause the parent process to be slow? Because the parent process runs a function that’s linear to the number all children process recursively.

However, this solves only half of the puzzle. If you remember the previous analysis, starting many child processes ALONE doesn’t reproduce the issue. If we don’t read the 2GB file, even if we create 2x more processes, we can’t reproduce the slowness.

So now we must answer the next question: Why does reading a 2GB file in the child process affect the parent process performance, especially when the workbench has as much as 480GB memory in total?

To answer this question, let’s look closely at the function __parse_smaps_rollup. As the name implies, this function parses the file /proc/<pid>/smaps_rollup.

def _parse_smaps_rollup(self):

uss = pss = swap = 0

with open_binary("{}/{}/smaps_rollup".format(self._procfs_path, self.pid)) as f:

for line in f:

if line.startswith(b”Private_”):

# Private_Clean, Private_Dirty, Private_Hugetlb

s uss += int(line.split()[1]) * 1024

elif line.startswith(b”Pss:”):

pss = int(line.split()[1]) * 1024

elif line.startswith(b”Swap:”):

swap = int(line.split()[1]) * 1024

return (uss, pss, swap)

Naturally, you might think that when memory usage increases, this file becomes larger in size, causing the function to take longer to parse. Unfortunately, this is not the answer because:

- First, the number of lines in this file is constant for all processes.

- Second, this is a special file in the /proc filesystem, which should be seen as a kernel interface instead of a regular file on disk. In other words, I/O operations of this file are handled by the kernel rather than disk.

This file was introduced in this commit in 2017, with the purpose of improving the performance of user programs that determine aggregate memory statistics. Let’s first focus on the handler of open syscall on this /proc/<pid>/smaps_rollup.

Following through the single_open function, we will find that it uses the function show_smaps_rollup for the show operation, which can translate to the read system call on the file. Next, we look at the show_smaps_rollup implementation. You will notice a do-while loop that is linear to the virtual memory area.

static int show_smaps_rollup(struct seq_file *m, void *v) {

…

vma_start = vma->vm_start;

do {

smap_gather_stats(vma, &mss, 0);

last_vma_end = vma->vm_end;

…

} for_each_vma(vmi, vma);

…

}

This perfectly explains why the function gets slower when a 2GB file is read into memory. Because the handler of reading the smaps_rollup file now takes longer to run the while loop. Basically, even though smaps_rollup already improved the performance of getting memory information compared to the old method of parsing the /proc/<pid>/smaps file, it is still linear to the virtual memory used.

Even though at this point the puzzle is solved, let’s conduct a more quantitative analysis. How much is the time difference when reading the smaps_rollup file with small versus large virtual memory utilization? Let’s write some simple benchmark code like below:

import osdef read_smaps_rollup(pid):

with open("/proc/{}/smaps_rollup".format(pid), "rb") as f:

for line in f:

pass

if __name__ == “__main__”:

pid = os.getpid()

read_smaps_rollup(pid)

with open(“/root/2G_file”, “rb”) as f:

data = f.read()

read_smaps_rollup(pid)

This program performs the following steps:

- Reads the smaps_rollup file of the current process.

- Reads a 2GB file into memory.

- Repeats step 1.

We then use strace to find the accurate time of reading the smaps_rollup file.

$ sudo strace -T -e trace=openat,read python3 benchmark.py 2>&1 | grep “smaps_rollup” -A 1openat(AT_FDCWD, “/proc/3107492/smaps_rollup”, O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3 <0.000023>

read(3, “560b42ed4000–7ffdadcef000 — -p 0”…, 1024) = 670 <0.000259>

...

openat(AT_FDCWD, “/proc/3107492/smaps_rollup”, O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3 <0.000029>

read(3, “560b42ed4000–7ffdadcef000 — -p 0”…, 1024) = 670 <0.027698>

As you can see, both times, the read syscall returned 670, meaning the file size remained the same at 670 bytes. However, the time it took the second time (i.e., 0.027698 seconds) is 100x the time it took the first time (i.e., 0.000259 seconds)! This means that if there are 98 processes, the time spent on reading this file alone will be 98 * 0.027698 = 2.7 seconds! Such a delay can significantly affect the UI experience.

This extension is used to display the CPU and memory usage of the notebook process on the bar at the bottom of the Notebook:

We confirmed with the user that disabling the jupyter-resource-usage extension meets their requirements for UI responsiveness, and that this extension is not critical to their use case. Therefore, we provided a way for them to disable the extension.

This was such a challenging issue that required debugging from the UI all the way down to the Linux kernel. It is fascinating that the problem is linear to both the number of CPUs and the virtual memory size — two dimensions that are generally viewed separately.

Overall, we hope you enjoyed the irony of:

- The extension used to monitor CPU usage causing CPU contention.

- An interesting case where the more CPUs you have, the slower you get!

If you’re excited by tackling such technical challenges and have the opportunity to solve complex technical challenges and drive innovation, consider joining our Data Platform teams. Be part of shaping the future of Data Security and Infrastructure, Data Developer Experience, Analytics Infrastructure and Enablement, and more. Explore the impact you can make with us!