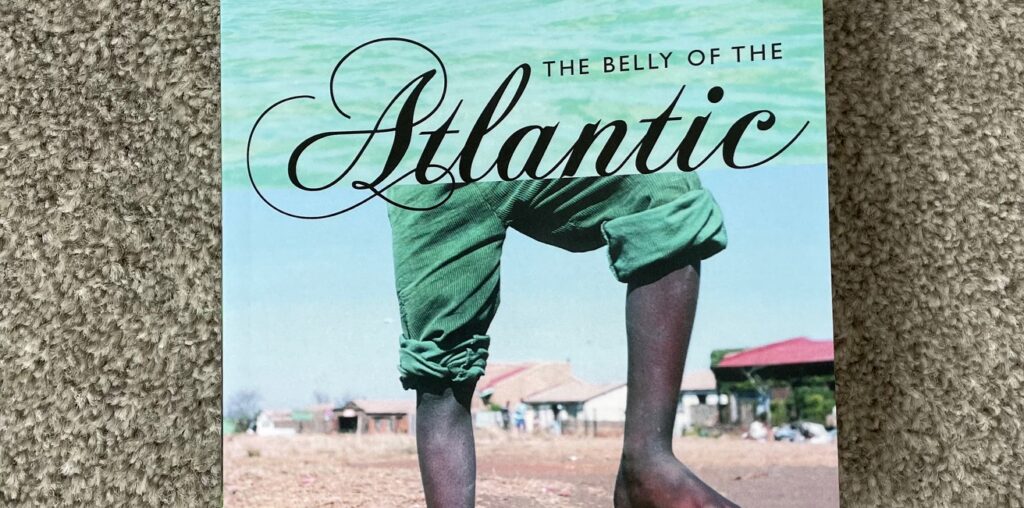

Don’t judge a book by its cover, the saying goes. Frankly, though, if I were assessing Fatou Diome’s The Belly of the Atlantic, translated by Lulu Norman and Ros Schwartz, on its appearance, I probably wouldn’t have picked it up. The pictures of the figure in the boat and the foot on the ball feel wearily familiar, if not a little clichéd.

Besides, although I’ve read and enjoyed football novels in the past – and know that a great writer can make any topic absorbing – I usually do so in spite rather than because of such subject matter. Not being a sports fan, I rarely find knowing a book is built around a particular game tempting.

But I did pick up this novel, which came out in French in the early 2000s and in English in 2006, for two reasons: partly because Senegal was one of the nations that had relatively few novels available in translation when I did my original Year of Reading the World, but also because I’m a particular admirer of the work of one of its translators: Ros Schwartz. Seeing her name on the title page suggested to me that this would be worth a try.

In fact, this book subverts the apparently familiar tropes of its cover in powerful ways. Narrated by Salie, who lives in France, the novel crystallises around a series of phone calls from her younger brother, Madické. A football fan with a difference, Madické is obsessed not with the French team beloved of his peers but with the exploits of the Italian player Maldini and needs to hear how every match he plays turns out. The one television on their home island of Niodior is temperamental to say the least, hence his SOS calls to his sister to fill him in. These conversations prove the catalyst for a series of reflections on and memories of Salie’s life, the immigrant experience, and the gulf that travelling from one world to another opens up between those who leave and those who stay behind.

The female perspective is part of what makes the book so striking. The opening descriptions of football mania and boys revelling in the beautiful game invite us to assume a male narrator. It is only gradually, with the repeated presence of strong, female characters, and strikingly direct observations about discrimination and the hypocrisy of patriarchal society, that the narrator’s position becomes clear. Indeed, it is only some pages into the narrative that Salie reveals herself as ‘a moderate feminist’ who ‘wouldn’t want testicles for the world’, and who looks with some disdain on the standards her brother is expected to conform to in order to satisfy her home society’s conception of ‘man’.

This covert disruption of what might be thought of as the default narrative voice for a book like this makes much about it fresh and startling, even twenty years after its publication. Familiar ideas are presented from new angles. And the tales of those who remain on Niodior, trapped in cycles of poverty and prejudice, gleam with troubling brilliance. The story of Sankèle, who pays a terrible price in an effort to escape an arranged marriage, is particularly memorable.

For a reader in the UK, the novel may seem uncannily prescient. In its exploration of the desire that many young people have to leave Niodior and try their luck in Europe, and its presentation of the grim reality and crushing obligations that await those who make the leap, the book seems to anticipate the stories that flooded Western media years later of African migrants braving horrific risks in search of a better life. For example, here’s Salie reflecting on the gap between Madické’s idea of her daily life and the reality:

‘It was no use telling Madické that as a cleaning woman my survival depended on the number of floor cloths I got through. He persisted in imagining I wanted for nothing, living like royalty at the court of Louis XIV. Accustomed to going without in his underdeveloped country, he wasn’t going to feel sorry for a sister living in one of the world’s great powers after all! He couldn’t help his illusions. The third world can’t see Europe’s wounds, it is blinded by its own; it can’t hear Europe’s cry, it is deafened by its own. Having someone to blame lessens your suffering, and if the third world started to see the west’s misery, it would lose the target of its anger.’

Of course, the fact that these words written in the early 2000s read as prescient to someone like me also shows up the selectiveness of the anglophone world’s storytelling: the so-called ‘migrant crisis’ is not a new phenomenon, Diome’s novel reminds us, regardless of what prevailing accounts of it may lead us to assume.

Structured as it is, the book can feel a little static. Salie is relatively passive – partly because she is trapped by her situation and partly because she is trapped by the past. As such, she is perhaps more in the position of one of the oral storytellers of her homeland, recounting rather than participating in events. The writing, however, brims with energy. Like its perspective, the novel’s imagery is fresh and striking, melding Senegalese traditions, nature and computer technology to paint the world in bold colours. If, occasionally, the narrative tips over into polemic, well, who are we to argue?

Reading The Belly of the Atlantic made me reflect on many things. It reminded me of the valuable way stories from elsewhere can disrupt, problematise and reshape the narratives that surround us. It also helped me remember how important older books are in anchoring us and counteracting the kneejerk impressions of the now. If we only ever read new titles – no matter how brilliant they may be – we can easily become detached from the threads of history, and lose sight of the lines and grapnels cast back down the decades that bind us to the world and to one another.

The Belly of the Atlantic by Fatou Diome, translated from the French by Lulu Norman and Ros Schwartz (Serpent’s Tail, 2006)