Far more complex, both politically and technically, was a divisive debate over whether to build the B-1 bomber, which presents a good lesson in how difficult it is, even for a president with a military background like Carter’s, to balance the appetites of what President Eisenhower called “the military-industrial complex” against his own prudent instincts. Only a week after his inauguration, the president met with military and budget officials to discuss whether to fund this technical marvel designed to fly at ground-hugging but supersonic speeds, under Soviet radar, to drop nuclear bombs on enemy territory. The plane was planned to supplement the aging fleet of B-52s that had once been the pride of the Strategic Air Command and was the aerial workhorse of the Vietnam War.

Carter said that he and not the Pentagon would personally decide what to include in the budget and therefore expressed the hope that “before I do, I can assess Soviet intentions.” Brown told him he had until the spring, because a new generation of cruise missiles was being built, and the numbers could be increased to serve as negotiating leverage in the SALT II talks. Carter commented: “A commitment to the B-1 says to Russia that we are still committed to the triple method of delivering nuclear weapons, and it will put pressure on them for reductions.” Sitting in and taking notes, I felt that these comments reflected a clear desire to move forward with the B-1, and so did everyone else around the table.

But because Carter’s campaign statements questioned the utility of the B-1, word was already filtering through to Congress that he was seriously considering killing the plane. In June the president met with a group of the B-1’s congressional supporters, including several representing districts where components would be built. They were led by Democratic Representative Sam Stratton, a strong defense advocate from upper New York State, who argued that there were

no good alternatives to the B-1 if the United States wanted to maintain the airborne delivery system of the land-sea-air triad. Another argument was that the costs could be trimmed by building fewer than the 249 planes in the Pentagon’s plans. Senator John Stennis, a Mississippi power on the Armed Services Committee and a strong supporter of Carter’s presidential campaign, took up the diplomatic argument in a slow, Southern cadence. He said construction had already started, and “Mr. President, to delay the B-1 further will put yourself in a hole on SALT.”

These arguments were tossed around the table until they reached the superhawk Senator Barry Goldwater, the Arizona Republican and Air Force reserve pilot, who unforgettably promised as a 1964 presidential candidate to “drop one into the men’s room of the Kremlin.” He stressed that the B-1 could stay in the air for 28 hours and pleaded: “Mr. President, don’t make the red [missile] button the only alternative.” He said that the B-52 fleet was so old that “the crews flying them now were not born when they started,” and in any case it would cost just as much to retool the aging fleet without achieving the speed and penetration promised by the B-1.

Carter listened carefully and then asked a series of questions indicating the depth at which he had examined the options. Since the Pentagon conceded that the B-1 could be easily detected by Soviet radar, he said the CIA indicated that the Soviet Union was far less concerned about the B-1 than about the new cruise missiles, which he supported. These unmanned air-breathing missiles could be fired outside Soviet borders, but penetrate deep into Soviet territory with pinpoint accuracy and less vulnerability to Soviet radar than manned bombers of any type—and by 1980, he asserted, the United States could produce 30 cruise missiles a year. He continued: “The total cost of the B-1 does not bother me, but if the B-52s armed with cruise missiles are as good and cost less, I will go with it.” Goldwater countered with a technical argument: It would take years for Soviet radar to be upgraded to detect incoming B-1s, and the planes could approach from any direction while cruise missiles would most likely come only from the direction of Europe.

Three days later, when Senators Ted Kennedy and George McGovern led the congressional opponents of the B-1 in their own meeting with Carter, I was struck that these liberals came nowhere near matching the expertise of their opponents. As well as I thought I knew Jimmy Carter, it also struck me how strange it was that a Southerner, an Annapolis graduate, and nuclear submarine officer would make common cause with this liberal group. I have never believed this arose from his religious convictions, or he would not have chosen a naval career to start with. On the contrary, I think it was his very service aboard nuclear submarines that imbued him with a deep awareness of the incredibly destructive capacity of the nuclear weapons that had been in his own hands. The liberals made many of the arguments Carter himself had already thrown back at the B-1 advocates. They emphasized the enormous cost of the bomber and argued that the money could be better spent on rebuilding our conventional forces or—like true liberals—on domestic programs. They made the political point that his position had been clear in the campaign and that recent polls showed a majority opposing the bomber. Kennedy urged him to focus instead on the country’s “human misery.” Carter closed the meeting by saying that he now had access to all the secret military information he had lacked as a candidate. As someone who was not a defense specialist, I was impressed by how strong the arguments were on both sides, coming as they did from different perspectives. To me, this is what the presidency is all about: making decisions when arguments are closely balanced.

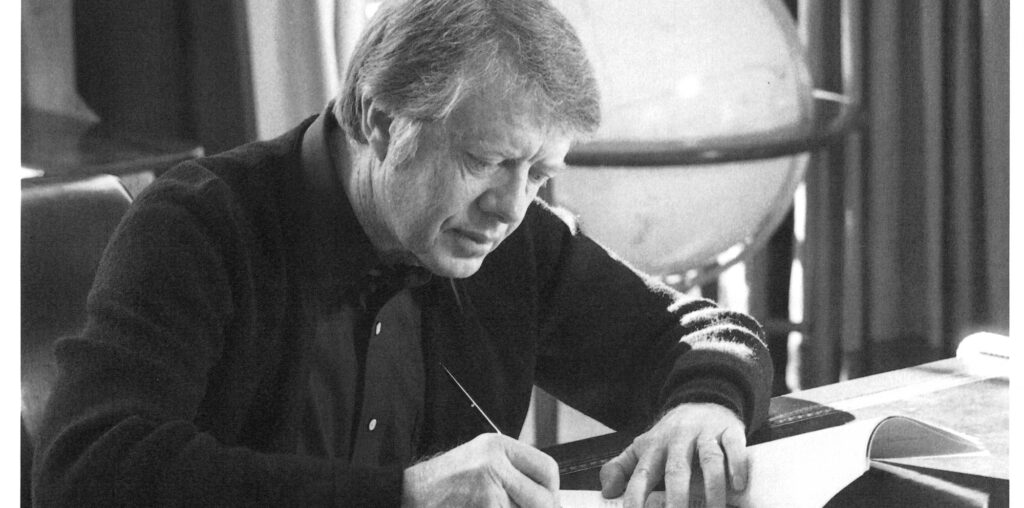

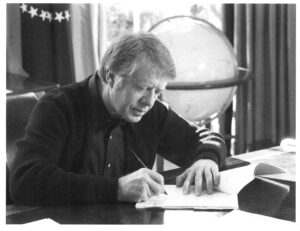

At the end of June the president called me into his study next to the Oval Office, where he did most of his reading, told me he would oppose the B-1 program—and that I would be the one to tell Brown. But first I would have to review the draft of the public announcement with Brzezinski. Neither of us discussed the merits of the decision Carter had just made, and I did not have the technical competence anyway. I instinctively felt it was substantively correct, but I was certain it was a serious political mistake and an early example of his compartmentalization of decisions.

However deeply the president had considered the technical and fiscal aspects, he had ignored an important diplomatic and political implication: The conservative senators were precisely the ones whose votes he would need to ratify the eventual SALT II arms-control treaty that meant so much to him. He already had the liberals on his side, and he needed to demonstrate to the doubters that he was strong and reliable on defense and thus co-opt them into a coalition that would muster enough votes for the treaty. As far as I know, there was no serious discussion among his national security advisers of the possible relationship between the two issues, nor had his principal political adviser, Ham Jordan, sat in on any of the meetings he held with members of Congress—on this or any other major issue during the Carter presidency.

I never found out why Carter asked me to go to the Pentagon in person and give the news personally to Brown instead of informing him over a secure telephone line. Perhaps he did not want to give Brown one last opportunity to plead the case for the plane. So, in the early morning of June 28, the White House limousine left me off at the Pentagon’s River Entrance. This was my first visit to this nation’s largest federal building, and by square footage, one of the world’s largest, with its five enormous, interlinked corridors. As I walked up the winding staircase toward Brown’s office, the sense of history was overwhelming as I passed the paintings of all former Defense secretaries. I was ushered into Brown’s huge office, handed him the presidential statement drafted by Brzezinski and reviewed by me, and told Brown that the president felt the B-1 was a costly insurance policy, and that while research and development on the plane should continue as a backstop, Carter’s mind was made up. Harold Brown is a brilliant and enormously able man, a physicist who had left the presidency of the California Institute of Technology to join the cabinet, and in my view its best member. He speaks in measured terms, without one superfluous word.

In the four years I worked with him, and in later subsequent government assignments, like the Defense Policy Board in the Obama administration, I had never seen him angry. But it was clear that he was unhappy with the decision and—with good reason—by the way it was being conveyed to him. He carefully walked me through the technical, strategic, and fiscal arguments and warned in characteristically measured terms: “I will have a hard time supporting any of the justifications for killing the B-1 before congressional questioning.” He went on to recommend that the cancellation statement should start by saying that alternative systems represented “better ways to do the same thing” and should avoid any implication that the B-1 was a complete waste of money. Carter followed this advice when the formal announcement was made on July 30.