A powerful city run by capricious rulers who favor bloodsport, deluding the masses, and expanding their influence with brute force through a vast network of empire? Well, enough about Hollywood, let’s talk about ancient Rome!

The phrase “he read classics at Oxford” makes someone sound like a proper gentleman—until you realize that tweedy brainiac had his nose in Pliny the Elder’s account of Empress Messalina’s duel with the realm’s most industrious prostitute, engaged in “continuous intercourse, night and day,” finally topping off at 25 gents in one go. (This golden nugget of classical lore was reenacted in the BBC television series I, Claudius, of all places—one of the more “feels like homework” productions of the last 50 years.)

A powerful city run by capricious rulers who favor bloodsport, deluding the masses, and expanding their influence with brute force through a vast network of empire? Well, enough about Hollywood, let’s talk about ancient Rome!

The phrase “he read classics at Oxford” makes someone sound like a proper gentleman—until you realize that tweedy brainiac had his nose in Pliny the Elder’s account of Empress Messalina’s duel with the realm’s most industrious prostitute, engaged in “continuous intercourse, night and day,” finally topping off at 25 gents in one go. (This golden nugget of classical lore was reenacted in the BBC television series I, Claudius, of all places—one of the more “feels like homework” productions of the last 50 years.)

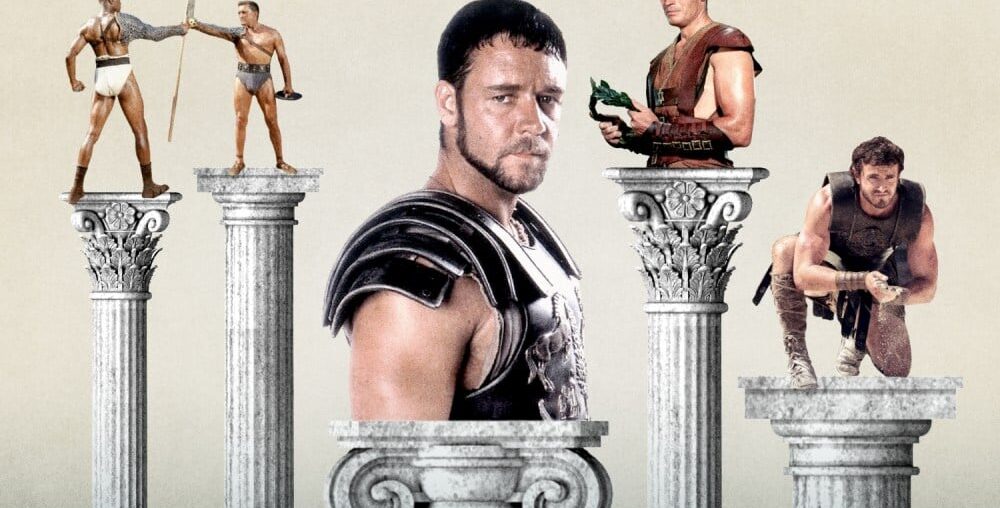

For well over a century, film producers have been infatuated with Rome. It’s easy to see the appeal—the setting has all the depravity, sex, and violence that gets butts in seats, but you can also slap on a coat of scholarship on top and get away with basically anything by saying “it’s educational.” This has been one of Hollywood’s great get-out-of-jail-free cards for decades, especially before the introduction of the MPAA rating system and its scrutinization of racier sequences.

“At least there’s a history lesson, unlike another mindless Western,” a parent might think as kids marched off to a matinée to see barrel-chested Steve Reeves hoisting women over his shoulders, or stuntman Yakima Canutt flung around an arena to the bloodthirsty cries of the crowd.

Kirk Douglas stars in “Spartacus.”Universal Pictures

Sure, the titular character in Spartacus (1960) really did lead a slave revolt, but when I saw it as a kid, all philosophical arguments about manumission took a backseat to the trident fights and the shirtlessness. Just so long as our main characters had a moral center, they could be surrounded by prurient scenarios that would never pass muster in another film at the time. In Spartacus’ case (to use one of several examples), there’s Jean Simmons’ body tossed around like a prize for gladiators who worked hard that day—and Kirk Douglas almost taking advantage until he realizes he’s being watched.

Finding loopholes in decency codes really hit its stride in the double-standard department with Bible epics, which were usually just Roman tales with a little religious pixie dust sprinkled on top. The very noble King of Kings (1961) was the first major studio release to show the face of Jesus (the blue-eyed Jeffrey Hunter) and positioned itself as a new way to share the Gospels. “You will behold the figure of Jesus Christ in a living characterization,” the trailer boasted. But I doubt if I’m the only one who was more enthused by Brigid Bazlen’s dance as Salomé for King Herod than the Sermon on the Mount.

Or consider the madness of Ben-Hur (1959). Sweaty, muscle bound men rowing in unison while one guard whipped them and another barked “ramming speed!” sure had me questioning some things when my parents sat me down to watch it. The moment when these same slaves, chained to their oars, realized a flaming ship was about to smash into them is as gruesome as the Saw franchise. And yet! This movie (“A Tale of the Christ,” as per the opening credits) is a religious picture.

With the social decay of the ensuing decades, Hollywood became less concerned with seasoning their offerings with make-believe morality, but there still is the allure of the prestige project. (Producers can get performers to do anything if they convince them there’s the possibility of an award at the end.) As such, there are two new projects set along the Tiber vying for your attention that, if you want to interpret them a certain way, smuggle in some reactionary politics like gift-bearing Trojans.

Russell Crowe stars in “Gladiator.”Universal Pictures

In theaters now you’ll find Gladiator II, the sequel to the runaway hit from 2000. The original, which starred Russell Crowe, was a massive financial success and also won the Academy Award for best picture. With the exception of Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (part three of a trilogy from an esteemed literary source), it’s one of only two best picture-winners this century that are basically “popcorn” movies. (The other, Everything Everywhere All At Once, certainly has lots of action, but its wacky universe-hopping concept makes it “weird” enough to be considered artsy.) The delay in the second chapter of the Gladiator saga lends itself nicely to a “next generation”-type story.

Crowe’s character died in the first one and regretfully no one visits a sybil to receive a vision of the actor, a little beefier these days, feasting in Elysium and dispensing sage advice. But the main character Lucius, played by Paul Mescal, is revealed to be Crowe’s son, who was smuggled out of Rome during a time of political tumult. Now, after leading Numidia in a fruitless defense against the expanding empire, he’s brought back and, just like Dad, ends up fighting for his life in the coliseum.

This goes down during the reign of nutty (even by Roman standards!) sibling emperors, Geta and Caracalla, who decide to keep the populace happy with the ol’ bread and circuses act. Games, games, and more games await, and that means director Ridley Scott (returning to the franchise) gets to film our hero battling spear-hurling, rhinoceros-riding foes one day, and paddling through shark-filled waters inside the arena the next.

What’s most interesting—apart from Denzel Washington’s exaggerated performance as the Rasputin-like Macrinus (a character very loosely based on reality)—is how the story positions our hero and his band of comrades as messengers of populism against the festering corruption in the palace. Through his mother, played by Connie Nielsen, Lucius is Marcus Aurelius’ grandson. (Marcus Aurelius was played by Richard Harris in the original.) Aurelius is remembered as a saint who only wished for Rome to ditch its current corrupt ways and return to being a republic. (There is no evidence that this was the case, and in a recent conversation, a notable classics professor informed me that anyone in Rome talking about a republic at this point in history would be treated like a modern American suggesting we return power to the British.) Anyhow, the good guys effectively lead a Jan. 6-style armed assault with an eye toward Making Rome Great Again.

Paul Mescal stars in “Gladiator II.”Paramount Pictures

Still, political messages mirroring modern events are certainly of secondary interest in Gladiator II. It’s mostly about seeing Paul Mescal and other hunks (Pedro Pascal and Peter Mensah among them) showing off their muscles and doing some cool fight moves. There’s a whole sequence with killer baboons. There are some thrilling moments, but all in all it lacks the heft of the original in its drama and visual snap. Maybe the whole “decline of the Empire” vibe soured some things for me, but I don’t expect a return to glory at the Oscars next year.

Meanwhile, on the streaming apps, Those About to Die debuted a few months ago on Peacock in the United States and Amazon Prime Video internationally. (Peacock’s launch was timed with the tail end of the Paris Summer Olympics, the streamer’s highest profile programming.) The quite expensive series is the biggest Roman television enterprise since HBO’s Rome, which aired five years after Gladiator hit theaters. (Prior to Game of Thrones, it was the cable network’s most spectacle-driven show, with ludicrous amounts of sex and violence, but also such a fine attention to detail that it had to close shop after just two seasons due to high costs.) Those About to Die boasts two-time Oscar-winner Anthony Hopkins in the first few episodes sporting some golden laurels, a white robe, and a big smile as the Emperor Vespasian.

The series was written by Robert Rodat, whose work on Saving Private Ryan got him nominated for a screenwriting Oscar, and is based on Daniel P. Mannix’s nonfiction book of the same title—which was a source of inspiration for the first Gladiator. All of which is to say this screams “prestige! prestige! prestige!” until you see that five of the 10 episodes are directed by schlockmeister general Roland Emmerich (Independence Day, Moonfall), who also served as showrunner.

The series is basically a sports drama in a toga, in which our hero Tenax (Iwan Rheon) decides that the only way to ensure a righteous future for Rome is to break the chokehold four families have on chariot racing. He runs a gambling concern beneath the Circus Maximus, and with the big bruiser Scorpus (Dimitri Leonidas) on his team, he’s bound to make some changes—so long as he can keep his champion away from strong drink and brothels long enough to best his foes! Tenax makes alliances with gladiators, slaves, the emperor’s brother, and more, and they’ve all got their own ambitions, which leads to a great deal of coupling and (sometimes gross) killing. It’s a silly show with an enormous cast (all the better for a high body count), and I cannot deny it is somewhat entertaining.

While I’d be hesitant to call Those About to Die deep or meaningful, it also has an undercurrent of “things were better in the old days.” It quickly recognizes that “bread and circuses” is only a Band-Aid for an unhappy populace, but has a nihilistic “if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em” attitude.

It’s interesting that both current Roman productions would lean on that premise right now, during a time of great dissatisfaction in American culture. Sure, we don’t have gladiator fights anymore, but we do have streaming services pumping us with more prestige programming than we know what to do with. And are you not entertained?

Seven Roman Recommendations in Addition to Mentioned Titles

I) Barabbas (1961): Anthony Quinn stars as the Levantine thief spared from crucifixion, whose road to redemption takes him to the Roman gladiator arena.

II) Caligula: The Ultimate Cut (2024): Originally released by Penthouse in 1979, this new version (one of three out there) excises most of the cheesy porno scenes and keeps Malcolm McDowell’s mad performance and Gore Vidal’s original dialogue.

III) Cleopatra (1934): Claudette Colbert rolled up in a carpet!

IV) Cleopatra (1963): Elizabeth Taylor rolled up in a carpet!

V) History of the World: Part I (1981): Probably the most accurate depiction of them all.

VI) Quo Vadis? (1951): Peter Ustinov’s Nero swishes it up as Rome burns.

VII) Titus (1999): One of the great MTV-inspired Shakespeare adaptations, starring Anthony Hopkins, Jessica Lange, and Alan Cumming.