This January marked the centenary of the formation of the First Labour Government. The product of an inconclusive election the previous month, in which the Conservatives won the most seats but were unable to win a parliamentary vote of confidence, Labour was able to form a minority government with the backing of the Liberal Party.

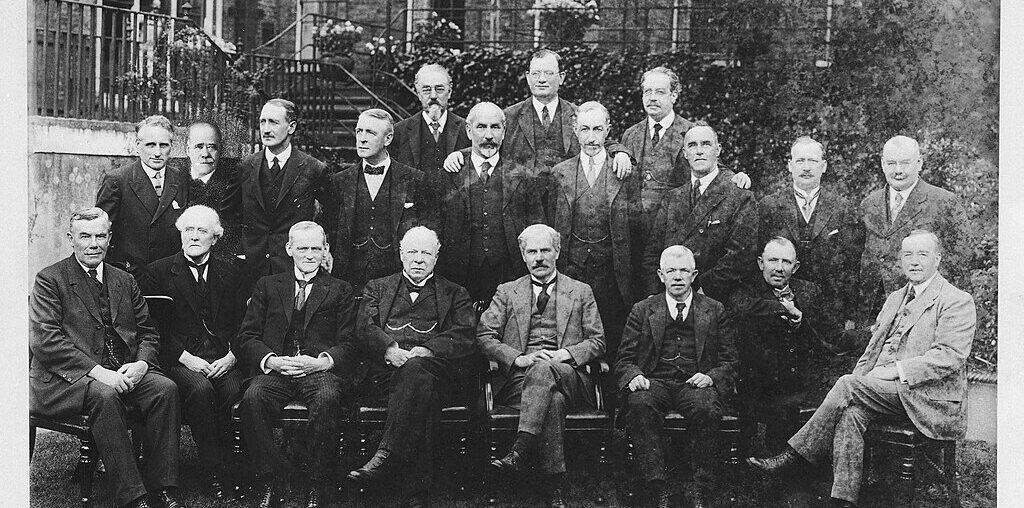

The coming to power of the First Labour Government has long been of great interest, due to the fact that it marked the first time that Labour, a democratic socialist party committed to radical social change, had come to lead the United Kingdom. Unsurprisingly, Labour’s ascension caused mixed reactions, with elements of the press incredulous at the thought of socialist “wildmen” running Britain, while the Annual Register, by contrast, referred to this historic event as representing ‘A revolution in British politics as profound as that associated with the Reform Act of 1832’. It also led to an overhaul of the two-party system, where for decades power had alternated between the Conservatives and Liberals; their traditional rivals. It was now Labour that held the mantle of chief rival of the Conservative Party; a role that it has continued to play to this day. Symbolically for a worker-oriented party, the new prime minister Ramsay MacDonald was the first person from a working-class background to hold that notable position.

Apart from the symbolism of Labour finally holding the reins of power after years in opposition, it is important to ask oneself what the Party actually achieved in office. One should not, I believe, celebrate a socialist government coming into being if it is unable to implement policies of social justice that represent the ideals of democratic socialism. The First Labour Government’s actions, however, certainly lived up to these.

War’s end

Labour came to power during a period following the end of the First World War when a number of other socialist parties came to power throughout Europe for the first time, either as senior or junior partners in coalitions. In Germany, the Social Democratic Party (the nation’s longest-established party) formed an all-socialist administration, while other European states like Hungary, Poland, Estonia, and Austria witnessed members of social-democratic parties assuming ministerial positions in office, enabling their members to have the opportunity to drive and influencepositive social change. British Labour was no different, although numerous policy proposals put forward during Labour’s time in opposition failed to see the light of day, hampered by the Party’s minority status in Parliament. A proposed capital levy never materialised, while Labour failed to secure passage of a number of bills such as one aimed at regulating rents and a private bill focusing on shop assistants’ hours of work. Despite these shortcomings, Labour succeeded in implementing a broad range of reforms during their relatively short period in office, many of which left an indelible stamp on society. Duties on certain foodstuffs were reduced, while improvements were made in financial support for the unemployed. Benefits were increased by a fifth for men and women, eligibility for payments to dependents was widened while more people were brought under the umbrella of unemployment insurance, and a statutory right to cash benefits was introduced. The government also acted to improve conditions for pensioners; raising pensions and extending the old-age pension to all those over the age of 70 in need. In regards to earnings, action was taken on trade boards, with the number of minimum rate enforcement inspectors increased by a third, Grocery Trade Boards revived (after having previously lapsed) and an official investigation launched into certain sections of the catering trade. Additionally, machinery for fixing minimum wage rates for agricultural workers (which was dismantled in 1921) was re-established.

Infrastructure

Emphasis was placed on developing infrastructure, with money made available for drainage, roads, and repairs and improvements for dwellings dating back to the First World War. Also of significance was the setting up of Royal Commissions on schooling and health insurance to formulate plans for delivering future changes in those areas (with the latter focusing on the uneven coverage of health insurance in Britain, amongst other aspects of the system), together with a Royal Commission on mental illness law, whose work culminated in important developments in provisions for people with mental illnesses in later years. Agricultural research received a sizeable cash injection, while the Small Debt (Scotland) Act offered support to poorer individuals in that part of the UK, with provisions such as a rise in the amount that could not be attached from wages and the direct payment by instalments of sums found due in small debt courts in rent arrear cases. As a sign of the spirit of the times, a parliamentary motion was adopted in March 1924 calling on the government to establish a Commission of Inquiry to look into the setting of minimum pay scales for working people.

The grant terms of the Unemployment Grants Committee, a body set up 4 years earlier to provide grants to local authorities offering work schemes to jobless persons, were also improved. More areas, for instance, became eligible for grants, while a 6 month probation of 75% or 87.5% of wages was eliminated and a stipulation introduced whereby contracts had to include Fair Wage Clauses. Provisions for war veterans and dependents were also improved, in keeping with the commitment made by Labour in its election programme to ensure “fair play” for this segment of British society.

True to its progressive principles, the First Labour Government reversed various austerity measures introduced in the years following the Armistice, which had entailed cutbacks in areas such as health, education, and housing. Cuts made to the educational system (including the abolition of state scholarships to universities) were reversed, a grant for adult education was bolstered, and an easing of regulations on the construction of schools was carried out. Efforts were made to reduce the number of unqualified teachers, while class sizes in elementary schools were brought down.Reflecting a policy adopted by Labour a year earlier to make universal secondary education a reality, the government increased the number of free secondary school places available; a policy development that resulted in nearly 50% of all secondary school children receiving their education for free by 1931.

Housing Act of 1924

Arguably the most radical measure of the First Labour Government was the Housing Act of 1924. The result of the work of health minister John Wheatley, this far-reaching piece of legislation, which raised government subsidies to housing let at regulated rents, facilitated the construction of more than half a million homes, increased the standard of council housing built, and included a fair wages clause for those involved in the building of these homes. This landmark law was, according to one historian, the First Labour Government’s “most significant domestic reform,” and to me represents a perfect example of progressive politics in action.

Despite these noteworthy accomplishments, Labour’s aforementioned lack of a legislative majority meant that it was unable to implement (in comparison with future Labour administrations) a programme of radical change, and lasted less than a year before losing the support of the Liberals and failing to win a snap election. In the run-up to this election, Labour was confronted with accusations that it was “soft” on the USSR, as arguably demonstrated by its recognition of and promise of a loan to the latter; decisions which possibly contributed to its electoral defeat.

The fate of Labour’s first administration was sealed by the controversy surrounding the “Campbell Case,” in which the government dropped a case put against the left-wing journalist John Campbell, who was accused of encouraging British troops to commit acts of mutiny by calling on soldiers to ignore orders to fire on striking workers if ever told to do so. A vote of confidence was held which Labour lost, and in the subsequent election, the Conservatives returned to office with a massive majority of seats in Parliament. Anti-communist propaganda deployed by Conservatives during the election campaign arguably contributed to Labour’s loss, with various Tory candidates equating the Labour Party with communism or leading Britain down this path. Both the Campbell case, along with the government’s building of bridges with the Soviet Union, gave ample ammunition for right-wing propagandists.

What helped their successful anti-socialist crusade was the publication in the Daily Mail (a few days prior to the election) of the Zinoviev Letter. Presumably from Communist International president Grigory Zinoviev to an official of the British Communist Party, the letter encouraged British communists to foment revolution. Although its authenticity remains open to debate, its likely that this document played a part in turning potential voters against Labour, bringing its first stint in power to a premature end.

Conclusion

In spite of its brevity in office, and the challenges it faced, it is to Labour’s credit that it was able to do so much, while demonstrating to voters that Labourites were democrats who believed in change through constitutional means and could be trusted to safely run the country while also being a credible alternative to the Conservatives. Undoubtedly, the positive achievements of the First Labour Government under the circumstances it found itself in demonstrated both Labour’s effectiveness as a governing party and its commitment to changing Britain for the better.

The lesson that progressives can learn from the record of the First Labour Government is that social change can be achieved even when a reforming administration lacks a majority in the chambers of power, as long as there is the will to do so. At the time of writing, Labour looks set to emerge victorious in the upcoming general election. If it does, a Starmer Administration should, in the face of a difficult economic situation, do its best to carry out as much in the way of social-democratic reform as possible if it wishes to make Britain a more just society for all in the years ahead. To do so would not only be to the benefit of ordinary people, but would serve as a great tribute to the memory of the First Labour Government.

Enjoy that piece? If so, join us for free by clicking here.