- chatbots offer answers to our questions

- when we write messages, predictive text suggests words

- Alexa can play our favourite song

- AI-generated deepfake presenters read the news

- In Arizona and California, we can ride in AI-controlled cyber cabs

- in Beijing last summer 27 AI-enabled humanoid robots attended a conference

- and at Teatro Verdi in Pisa, on September 12, a mechanical maestro called YuMi conducted Andrea Bocelli and the Lucca Philharmonic Orchestra.

Making a significant — though largely unrecognised — contribution to all these initiatives was Cork academic George Boole.

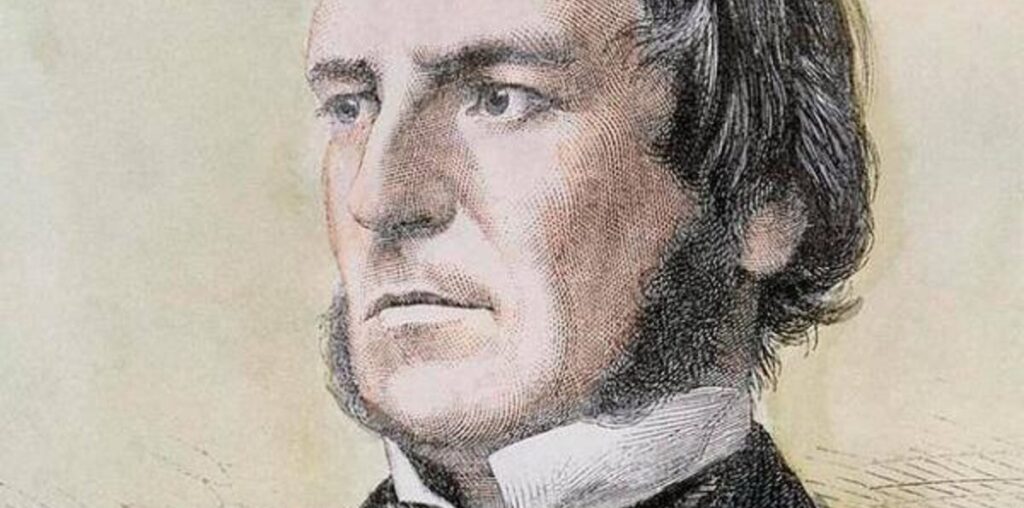

Born in the small English cathedral town of Lincoln in 1815, George Boole came from a humble family: his father was a shoemaker, struggling to support four children. A classmate described him as inquisitive, “a sort of prodigy… a star of the first magnitude”.

Having left school at 14 years-old, he helped his father build telescopes, kaleidoscopes, even a calculating machine. His translation of a difficult poem from ancient Greek caused outrage: many said this was impossible for a boy of his age, he must have had assistance. Boole went on to write over seventy poems of his own.

When his father’s shoe business collapsed, 16-year-old George turned his back on a possible career in the church, and took up school teaching in Doncaster and Liverpool to support his family. Returning to Lincoln in 1834, he daringly set up his own school, and moved his family into the schoolhouse. By getting involved with the Lincoln Mechanics’ Institute, he helped provide an education to adults who’d missed out on school.

Boole had a voracious appetite for reading, and taught himself French, German and Latin, but said he got better value from his maths books than novels because they lasted him longer. Strangely, the quiet man never described himself as a mathematician, rather a psychologist, philosopher and logician.

“We have a mathematician trying to work out how the mind works”, writes his biographer, Desmond MacHale (The Life and Work of George Boole, Cork University Press, 2014).

When he was 28, Boole wrote to Professor Augustus de Morgan at University College London, to help him get an article published by the Royal Society. The paper was not only accepted by these eminent scientists, they also awarded him its first gold medal for mathematics. Boole’s name became well known in academic circles… but he was still without a job.

The British government’s decision to establish ‘Queen’s colleges’ in Ireland gave him the opportunity he needed. However, with no formal qualifications, his only chance of getting a chair was to rely on his publications and testimonials from academic friends, even character references from people living in Lincoln. “My hopes of success are not very sanguine”, he admitted.

For months he heard nothing. Suddenly, in August 1849 he received a letter offering him the post of Professor of Mathematics at Queen’s College Cork (UCC), with an annual salary of £250 and lodgings on Grenville Place, opposite North Mall.

Cork was “perfect for an independent thinker”, a “maverick”, who at Cambridge University would have been overshadowed, says MacHale. The Cork Examiner (Nov 8, 1849) described him as “well developed in the frontal region, as a phrenologist would say”. Regarded as a “confident”, “modest” and “gentle” teacher, he always had the welfare of his students at heart, and complained about the smoky chimneys and echo in the lecture rooms.

Boole became “the prototype of an eccentric professor”, pacing up and down deep in thought, and bringing home complete strangers — on one occasion a whole street band — just because he found them interesting. But he found Cork “uncomfortable”, and couldn’t stand all the rain. He made frequent trips back to Lincoln, and even considered taking a job in Melbourne.

In 1850 he was asked to give maths lessons to Mary Everest, a shy 18-year-old girl, niece of George Everest, after whom Mount Everest is named. Teacher and pupil kept in contact, and in 1855 shocked friends by announcing their marriage: he was 40, she was 23.

Five daughters were born in quick succession. Ethel Lilian (Voynich), the youngest, came to write , a novel that sold millions of copies in Russia and China. The couple lived first on Sunday’s Well Road, a 10-minute walk from college, later in a house overlooking the sea on Castle Road outside Blackrock, and finally at Lichfield Cottage in suburban Ballintemple”.

Mary went to some of his lectures — possibly the first woman in Ireland to attend university classes.

Boole’s masterpiece, , was published in 1854, and helped towards his appointment as Fellow of the Royal Society in 1857 — an extraordinary achievement considering he began as a lone wolf schoolteacher. In his book, Boole maintained that every human thought has two outcomes, every whim can be reduced to a mathematical operation: ‘yes’ or ‘no’, ‘true’ or ‘false’, ‘on’ or ‘off’, ‘1’ or ‘0’ — just like the symbols on the switch of an electric kettle.

When reasoning, speakers of every language use three words: ‘and’, ‘or’ and ‘not’, continued Boole. By giving these words mathematical symbols (∧, ∨, and ¬), it was possible to control them. Today, they can be used in computer programmes.

‘Boolean Algebra’ and ‘Boolean Logic’ paved the way for designing modern, high-speed computer circuits and relays. These days, “every keystroke on your computer, every swipe on your phone, every answer from Siri can be traced to Boole. We are awash in Boole”, says Canadian technology buff Ava Chisling.

Although the expression ‘Artificial Intelligence’ wasn’t used until 1955 by American academic John McCarthy, “Boole’s work provided the groundwork for many AI algorithms today”, says philosopher Antonio Panovski.

Boole’s teaching duties were demanding — he had 73 students, more than any other teacher — and placed a huge toll on his health. Clashes with college management, and a mysterious fire which burned down his office, added to this stress.

On November 24, 1864, when his train was cancelled, he walked three miles in pouring rain from his home in Ballintemple to Queen’s College, where he lectured in saturated clothes. That night he developed a feverish cold, which settled on his lungs. Delirious and unable to speak, doctors concluded that his brain was in “the most alarming condition”.

Mary Boole was an advocate of ‘fringe medicine’, especially homeopathy, which believes in treating the illness with the cause. Seeing as her husband’s illness was caused by exposure to rain, moisture could restore him to health, so she laid him in wet linen. On the evening of December 8, aged only 49, George Boole died from pneumonia.

Although only a simple headstone marks his grave at St Michael’s Cemetery, Blackrock, Boole’s name lives on at UCC, where the library bears his name, and a panel in the Boole Memorial Window depicts him as a medieval scholar, diligently at work.

“If Boole had lived”, speculates MacHale, “we might have had the computer revolution in the 19th century, rather than the 20th and 21st century”.

Be that as it may, he would surely be chuffed — in his quiet way, of course — that today an AI-driven self-emptying robot vacuum cleaner and mop combo, called the ‘Boolean Cloud H7’, can clean people’s homes when they tap on their smartphone.