- The creator economy, a sprawling industry worth $150 billion and projected to reach $500 billion by 2030, is not just an evolution of influencer culture but a response to changing audience expectations. Authenticity is increasingly a competitive edge.

- The erosion of trust across American life forced creators to pivot from mere promotion to delivering value through high-quality, engaging content. This led to a separation between influencers, who rent their audiences to brands, and “creators,” who rent their creative skills to brands with an audience in tow.

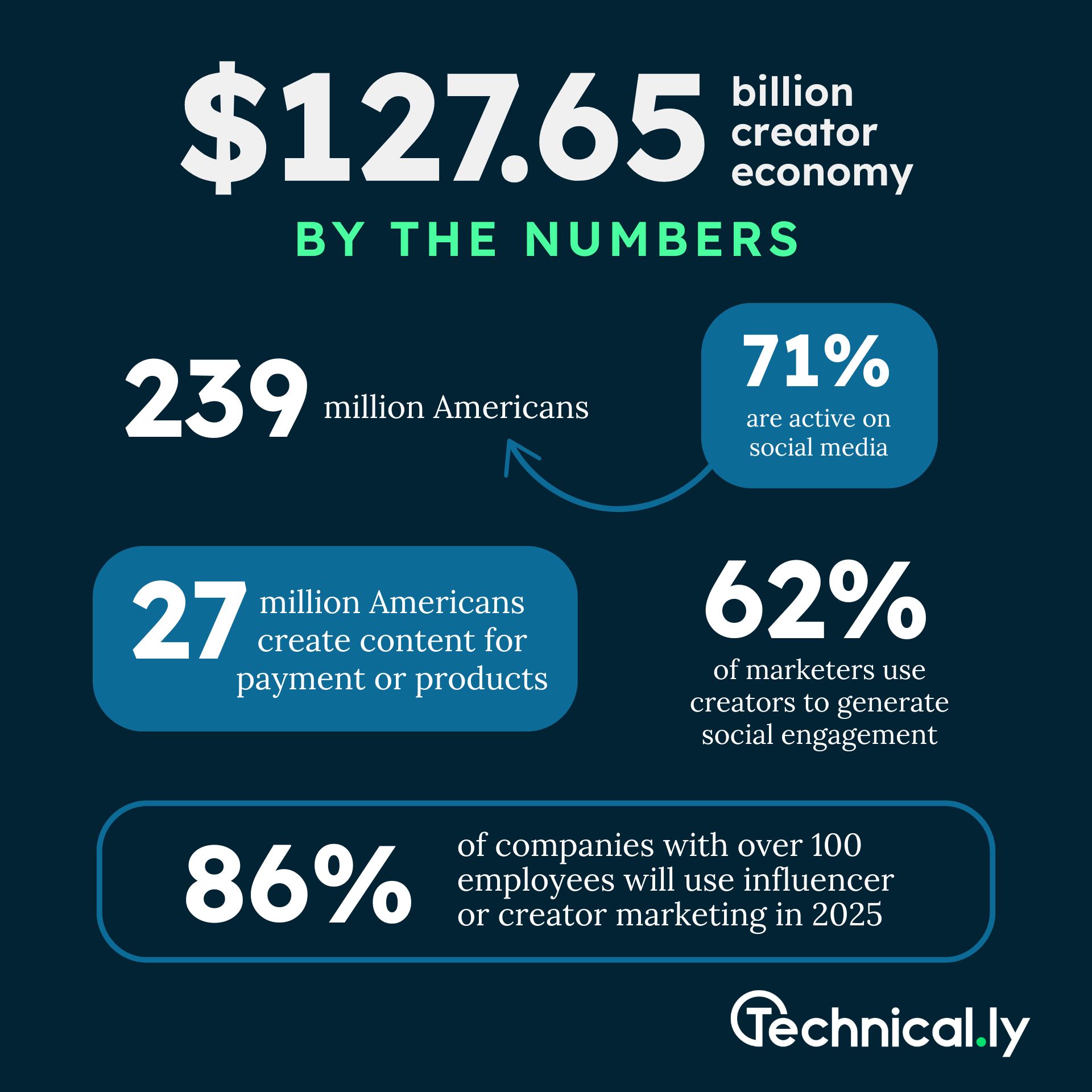

- Over the past decade, there was a significant surge in people who create online content for money. Most of us consume this content; brands are increasingly collaborating with creators to reinforce messaging; and it’s becoming a primary mode of information sharing.

→ Read on for details and join Chris Wink’s weekly newsletter for more

In March 2015, Lord & Taylor promoted its new Design Lab collection with what had become a standard style marketing campaign.

In addition to magazines, the retailer gave 50 fashion influencers a free paisley asymmetrical dress and paid them $1,000 to $4,000 each to post styled photos on Instagram. The influencers’ combined posts reached 11.4 million users in just two days, leading to 328,000 engagements and a sold-out dress.

The problem: none of the influencers disclosed they were paid to promote the dress. Someone somewhere lodged a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission, which was following the rise of undisclosed paid social media posts. Back in 2013, the FTC had organized hearings to set standards. Regulators wanted to set an example, and the Lord & Taylor campaign fit.

In early 2016, L&T reached an agreement with FTC, giving the commission a chance to make a splashy announcement and introduce new “native advertising” guidelines. Among the requirements were clearer disclosures on paid posts, using “#ad” or similar markers.

Industry watchers warned it could kill influencer marketing. Surely, audiences would tune out content so obviously labeled as advertising. But, as documented by longtime creator-journalist Taylor Lorenz in her 2023 book “Extremely Online: The Untold Story of Fame, Influence, and Power on the Internet,” the opposite happened.

By 2018, influencers promoting Christian Dior’s saddle bag were tagging “#ad” even when they weren’t paid. Getting a paid promotional gig was a signal of influence, and it seemed every fashionable social media creator wanted to be an influencer.

The FTC guidelines inadvertently raised the bar for authenticity and creativity. Influencer marketing wasn’t killed, it evolved into a subset of what is called the creator economy, a sprawling industry worth $150 billion and projected to reach $500 billion by 2030. Definitions vary, so the numbers do too. About 250 million Americans engage with social media daily, and of them, about 27 million get paid for it — whether that means a share of advertising from a platform like Youtube, individual supporters via Patreon or direct payment or free products from a brand.

So, what does the creator economy mean for the rest of us, both as buyers and as consumers?

The shift from influence to creation

The creator economy isn’t just an evolution of influencer culture—it’s a response to changing audience expectations.

Trust is declining across American life. A bruising pandemic accelerated declines in the approval Americans have for practically all great institutions of public life: government, university, science, corporations, the courts, the media and even religious groups, per Pew research released last month.

The only groups that bipartisan majorities of Americans say they trust are small business and the military — cops and educators still fare OK, but it’s going the wrong way.

Even the once mighty influencer has fallen. Only 2.2% of Americans say they trust influencers for purchase advice, according to a new survey from Reviews.org. This “isn’t surprising because most influencers aren’t trained experts and often are just posting sponsored content,” said the survey’s managing editor Peter Holslin in the release. (Note: I’ve seen higher trust ratings for influencers but typically about topics, not purchases.)

Only 2.2% of Americans say they trust influencers for purchase advice.

Herein marks a separation between influencers, who rent their audiences to brands, and “creators,” who rent their creative skills to brands — with an audience in tow. This matters because across decades of research on trust, one obvious trend is clear: The globally connected online world is training a more skeptical public to seek disinterested parties and those we’ve known for a long time.

That Reviews.org survey estimated trust in user reviews above 30% and trust in friends and family closer to half. (For those who doubt the recommendations of your loved ones, I see you.)

This trust divide runs counter to strategies from the corporations behind social media platforms. In the 2010s, Facebook and Twitter were structured for users to mostly follow people they knew personally — which insiders call “the social graph.” Despite political pressure, TikTok’s surging popularity has been defined by its “For You Page,” in which users are served up videos about stuff they like, not necessarily people they know, and Youtube has long prioritized not personal relationships but topics — what is called “the interest graph.” Facebook and Instagram followed. Even earnest Linkedin launched in March 2021 a creator mode to support influencers speaking to fans they don’t know.

This erosion of trust has forced creators to pivot from mere promotion to delivering value through high-quality, engaging content — better to create some semblance of connection. Just 40% of marketers hire creators to directly boost revenue (ie. sell that paisley dress for me!), and more than two-thirds work with them to boost social engagement, reinforce brand or as pure staff augmentation, per a SproutSocial survey. Marketing execs typically advise creators are better for boosting engagement than closing deals.

Who calls themselves a professional creator?

Adobe’s most recent creator survey estimated 500,000 people globally were full-time creators, and barely 1 in 10 made more than $50,000 a year — with a tiny sliver earning large sums. Or are there 11.6 million full-time creators in the United States alone? That’s what a different November 2023 analysis estimated, a figure that would mean there are three times as many creators as software developers, and or five times as many as marketers.

I spoke to Ed Keller, the market research veteran behind that last analysis. “If the number of full-time creators seems high,” Keller told me, “I have confidence in it.”

A 2018 Bureau of Labor Statistics analysis projected that by 2026 a slate of creative workers, including photographers, writers and animators would be self-employed — a cohort of 50,000 or so possible full-time creators. Different surveys may vary on the numbers, but not the trend. Over the past decade, 2021-2022 recorded the fastest surge in those creating online content for money, per MBO Partners.

“For a lot of people, the pandemic changed things,“ Keller said. “People were in a mode of looking for an outlet and other people were looking to find somebody to follow. Creators had the right idea at the right time with the right tools.”

“Creators had the right idea at the right time with the right tools.”

Ed Keller, Market Research Institute International

Without government data or tax records, a “fulll–time” creator is a self-identification. Might a marketer or software developer call themselves a creator, even if their employer doesn’t? A tax attorney told me there’s little consistency in how so-called creators would be categorized in government data, like the NAICS codes of companies they form or in the occupation codes they might use for their taxes.

This backs us into one reason the creator economy matters: We’re still shaping what it means that more than half of young people today report they can “easily” make a career of creating content online for some audience, per Morning Consult.

This matters for other reasons too. For one, most of us consume the stuff. About three-quarters of Americans use at least one of the platforms on a regular basis. Increasingly it’s less about updates from our friends and more a stream of strangers, celebrities and a fledgling workforce that is somewhere in between.

If you don’t rely on makeup or sourdough tutorials, you might seek game reviews from a Twitch streamer, science explainers from a TikToker, silly memes from an Instagram account or car repair tips from a YouTuber. What motivates this labor, then, informs what content you can access, where and why.

Others of us are both consumers and creators ourselves — I think most journalists should be — and so these trends shape our work. Still others of us may not be the creator but will hire them.

Brands long ago recognized the importance of so-called “ambassadors,” our fans who will write online reviews, post to social and share testimonials. This organic activity remains vital. The creator economy, which implies a monetary exchange, is something different, and it is growing.

In 2025, 86% of companies with more than 100 employees will use influencer or creator marketing, per Statista. We at Technical.ly are piloting a creator-in-residence program, in which we’re paying comedian Tata Sherise to translate our journalism for new audiences. It’s about sharing our work and shaping how people think about our news organization. (We also added a best local creator category to our annual awards.)

Creators are not just promoting products; they’re co-creating narratives that resonate deeply with their audiences. I bet this will matter more, not less, as generative AI tools flood the digital space with automated content. While AI can churn out text and visuals at scale, it cannot replicate the trust and authenticity that come from human creators.

Authenticity is a competitive edge.

How does working with creators…work?

Creators now span a wide spectrum, from nano-influencers with hyper-engaged audiences to macro-creators commanding millions of followers.

Stories of excess dominate the narrative: Canadian streamer xQc signed a $100 million deal with Kick, outpacing even LeBron James’ recent NBA contract. But each creator approaches things differently. An old rule of thumb was that an Instagram creator charged $100 per each 10,000 followers for a post, signaling just how commodified audience had become. A recent Shopify analysis puts more granularity to estimated costs, but prices vary with expectations.

From those old days of buying influence to one in which creators are collaborators, pricing can look less like an alternative to display advertising (how to most cost effectively reach 1,000 accounts) and more like a fee for service (help us translate our story to your audience).

Most creators — and, in my telling, news orgs like Technical.ly are both creators and curators of creators — have clearer processes and pricing models. If you follow a social media user with a style and a following you’d like to reach, check their bio link for a website that typically has contact information. Some have fixed pricing (think of celebrities on Cameo), but more often they take a collaborative approach. (We at Technical.ly do something similar here,)

A lesson from Lord & Taylor

A decade ago, the Lord & Taylor campaign and ensuing FTC action was a turning point for marketing, and the social web. That year, a Technical.ly conference speaker dubbed it the “year of the influencer.” That gave rise to competition for ever more creative storytelling.

The internet is a crowded bazaar. Guides are helpful. The creator economy is an imperfect phrase for a very real trend: brands seek audience, and audiences congregate around helpful information and great stories.

In an essay published on Microsoft’s website in January 1996, Bill Gates wrote what has become an axiom of the digital age: “Content is king.”

Transparency and authenticity will help cut through increasing clutter.