England’s greatest, weirdest living author lives in a terraced house in Northampton, where he worships a snake god in the basement. Alan Moore revolutionized the comics industry in the 1980s with Swamp Thing, in which a nearly forgotten character was turned into an exploration of the United States’ environmental and historical horrors and glories, and Watchmen, a wildly innovative work often described as the Citizen Kane of comics.

Since then, he has written numerous graphic works (A Small Killing, Providence, and From Hell, to name just three), regular novels (Voice of the Fire, Jerusalem, and The Great When), and a nearly uncountable number of stray comics. He’s also refused to take a cent from the more than $500 million in box office sales that his works’ movie adaptations have made.

The Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic, Alan Moore and Steve Moore with various artists, Top Shelf Productions, $49.99, 352 pp, October 2024.

His new book, The Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic, written with fellow comics author Steve Moore (no relation) and illustrated by an wide array of artists, is a self-help manual for a “fulfilling new career as a diabolist.” Like the book itself, this claim is both a joke and entirely serious. The authors want you, the reader, to become a magician—but for them it’s more about creative inspiration than conjuring the spirits of the damned.

Alan Moore is the most prominent of the wave of British talent—including Garth Ennis, Grant Morrison, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis—that came to dominate the U.S. comics industry in the 1980s and ’90s. They were mostly young men from working-class backgrounds, few of whom had attended university. Moore himself was kicked out of his secondary school for, as he put it in one interview, being “one of the world’s most inept LSD dealers.”

Comics, simultaneously culturally undervalued and offering room for wild experimentation, gave this group their canvas. Alan Moore’s detailed, deeply researched, and wildly imaginative stories became instant classics: Watchmen, his most famous graphic novel, sells tens of thousands of copies each year. His takes on iconic characters like Superman and Batman still shape their portrayal today. But, by the 1990s, he was burned out on superheroes, working instead on historical fiction like From Hell, in which he explores the Jack the Ripper murders and the mythologies around them.

Steve Moore, a friend of Alan Moore’s since they were both teenagers, was a comic book writer who left school at age 16. He was also a serious scholar, almost entirely self-taught, of the Yijing—an ancient Chinese divination text—and a member of the Royal Asiatic Society.

He also died a decade ago; this book, due in part to the difficulty in corralling so much artistic talent, has taken over 15 years to put together. It is a compilation, using both art and text, of their shared ideas on magic, society, and creativity—and perhaps the last gasp of a distinctly local take on the occult imagination.

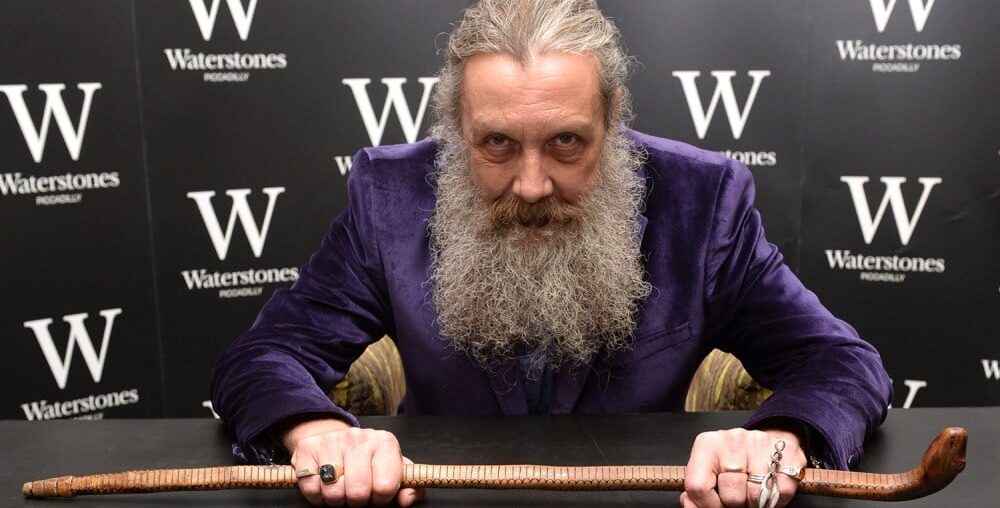

Author Alan Moore attends a book signing in London on Sept. 6, 2013. Rune Hellestad/Corbis via Getty Images

In 1993, when he turned 40, Alan Moore announced in his local pub that he was going to be a magician and took up the ceremonial worship of Glycon, an obscure Anatolian snake god whose cult enjoyed a brief period of popularity in second-century Rome. As they recount in the book, the two Moores formed the world’s smallest magical cabal around January 1994, when they had a joint revelation that “in a space time continuum of four dimensions, every entity and every moment is eternal.” They also had a vision that they had “intruded on a space of blinding whiteness where the discarnate, timeless idea-forms of great magicians resided as a literal illuminati, a convergence of illuminated minds beyond the boundaries of material existence.”

It may be relevant that both authors were extremely high on mushrooms when this revelation occurred.

Like serious mystics, however, the vision itself was only the start of what they describe as a two-decade process of understanding it. As part of their quest, Alan Moore started organizing performances under the name “The Moon and Serpent Grand Egyptian Theatre of Marvels,” mixing art, poetry, and music to create new magical “workings.” These sessions were situated within a long English tradition of artistic interest in the occult.

In the live shows, the framing conceit was the traveling circus sideshow, offering “curiosities to suit your every inclination, demonstrations and displays, unique sensations, and a previously unimagined sexual extremity included in the modest cover fee.” The book, on the other hand, echoes the children’s activity books that were popular during the Moores’ youth in the 1960s and ’70s, which, like the traveling show, are now an almost vanished genre. It promises to offer “all you need to know in order to pursue your own investigations and experiments” in magic.

Demonstrators gather for the Million Mask March, organized by the group Anonymous, in London on Nov. 5, 2017.Niklas Halle’n/AFP via Getty Images

Magic, for the Moores, is somewhere between metaphor and spiritual practice. It’s a way, like art, of exploring the rich territory of internal worlds, following the maps offered by tools like kabbalah and the tarot, and shaping that personal internal world in a way that influences the collective imagination. Fictions can shade into reality. Gods and demons are created out of the human psyche, but that doesn’t make them less influential or powerful. For Alan Moore, for instance, that happened when his tale of a revolutionary wearing a Guy Fawkes mask, V for Vendetta, led that mask to become a symbol of global protest.

So what’s actually in the book? Like the ceremonies, it’s a jumble of ideas. It includes long essays on the Moores’ understanding of magic; “Old Moore’s Lives of the Great Enchanters,” which is a comic-strip version of the lives of historical magicians and occultists from Circe to William Blake; a long pulp story over multiple chapters about a woman magician of the 1920s; and a cut-out Egyptian temple to build at home.

Artistically, parts of this work better than others; I wish they had stuck more closely to pastiching the style of the bumper book for children. The essays are badly in need of an editor; they steer into pretentiousness rather than playfulness. The illustrations, however, are wonderful, intricate, and clever—as are the graphic stories, especially the Steve Parkhouse-illustrated “The Morning of the Mind,” a wordless depiction of the birth of prehistoric religion.

A selection of pages from The Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic by Alan Moore.

Yet I was most struck by how both Moores combined an intense localism with a deeply cosmopolitan and exploratory spirt, built on both the collective unconscious and the layers of a haunted past. Steve Moore spent virtually his entire life living in the same house in south London, where several of his neighbors claimed to have seen him in the garden two days after he died in the same bed he was born in, as Alan Moore recounts in the book’s epilogue. Steve Moore’s only novel, Somnium, is set over the course of four centuries within the walls of his local pub.

The psychogeography of Steve Moore’s life and his neighborhood was the subject of a spoken word piece, later turned into a book, by Alan Moore, Unearthing. Alan Moore himself, despite the global success of his works, has never lived outside of the large town of Northampton, where he is a much-beloved local figure, nor lost his strong Midlands accent.

When I discussed one of Alan Moore’s longest and densest books, the 1,300-page Northampton-set Jerusalem, with an old friend who still lives opposite my childhood house, he spoke of how he valued the book for being one of the few modern novels to speak to people like him, who spend most of their lives in the place they were born.

In the United Kingdom today, localism is often associated with a spirit of “Little Britain”—a pinched, xenophobic, and Brexit-esque view of the world. The Moores’ work comes from an entirely different tradition, where digging into the layers of the place you come from, and your own mindscape, can reveal ideas and emotions shared with the entire world. There aren’t many writers doing that kind of digging today, especially from the political left. (Alan Moore has always been a fierce activist, including for LGBTQ+ rights.)

As a history of magic and religion, the book should be taken with a healthy dose of salt. Take the figure of the “sorcerer” that bookends the work. This is a famous image from a prehistoric cave in France, purportedly showing a dancing magician who mixes aspects of animal and human. Unfortunately, though, the cave painting looks different in reality, and the image seems to have been largely invented by a French archaeologist in the 1920s.

There are some sweeping claims that should give a reader pause. I don’t think, for instance, that “the union between Jews and Protestants that Christian Kabbalah made possible would be a significant factor in the creation of the state of Israel.” For a detailed, scholarly take on the influence of the occult in England, I would turn instead to Ronald Hutton’s work, such as Witches, Druids, and King Arthur, or Francis Young’s political history, “Magic in Merlin’s Realm“.

But the authors are aware of how blurry the lines are around the histories they relate—and how the fiction can be more important. The magician whose history is related at the greatest length is Alexander of Abonoteichus, a second-century charlatan and the creator of the snake god that Alan Moore himself worships, Glycon, who in real life was a drugged python in a blonde wig. Alexander’s life is told in a series of Mad magazine-style comic strips that dub him the “quack with the knack” and the “fake with the snake.”

For Alan Moore, as he described at length in one story, Glycon’s great advantage as a god is that he is verifiably false. As he has “Glycon” say, “This is the only way gods manifest, in paint, and props, and poetry. I am not the docile python, or the false head, or the borrowed voice. I am the idea that generates these things.”

We live in an age dominated by angry ideas and pervasive fictions. The Moon and Serpent is about creating ideas that blur into reality, but as Alan Moore has remarked, “The big advantage of worshipping an actual glove puppet, of course, is that if things start to get unruly or out of hand, you can always put them back in the box.”