The concept of a prequel is a well-worn one in literature. Not only did authors like J.R.R. Tolkien further flesh out their characters and worlds in books set before previously published adventures, but L. Frank Baum, author of “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz,” wrote “Ozma of Oz,” the first prequel to be set in that particular universe. In cinema, however, the concept took a while to catch on, and it wasn’t really until “Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace” that the cinematic prequel became popular. To say that the process had some bumps in the road would be an understatement; “The Phantom Menace” and its two sequels were loudly reviled upon their initial release, with everything from their characters to their dialogue to their visual aesthetic taken to task for not looking or feeling enough like the original “Star Wars” trilogy. Despite George Lucas’ claims that the films were intended to be watched in episode order, it’s more apparent in hindsight that Lucas wasn’t merely making a straight prequel trilogy, but a revisionist one. It’s for this reason in part that the Prequels have undergone a recent wave of reappraisal.

Jon M. Chu’s film version of “Wicked,” an adaptation of the stage musical that itself adapted Gregory Maguire’s novel, didn’t necessarily need to connect itself to the 1939 “Wizard of Oz.” Yet the fact that it does so makes it a prequel. Its revisionism, of course, is essential, as it’s the text of both the novel and the musical, which tells the tale of how a wave of falsehoods, scapegoating, and propaganda allows Elphaba Thropp (Cynthia Erivo) to become known as the Wicked Witch of the West. Therefore, “Wicked” the film ends up feeling remarkably like the movie musical version of the “Star Wars” prequels.

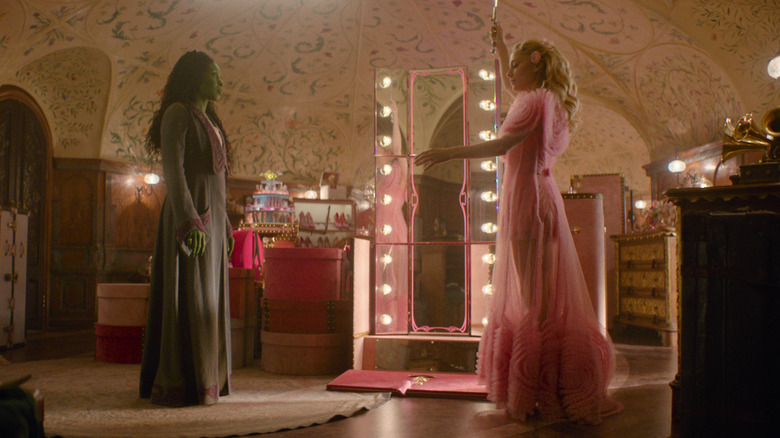

‘Wicked’ and the Prequels share a gaudy visual aesthetic

If you’re a movie fan and you’ve been on social media in the last few months, you’ve undoubtedly caught wind of the poor reputation “Wicked” has already garnered for its choices regarding CGI, set design, and most particularly its cinematography and color grading. Of course, a good portion of this bad rep can be chalked up to the way video is encoded on social media apps, as well as playback settings on everyone’s various devices. Still, there’s no doubt that the finished film looks A Certain Way. Setting aside larger discussions of changing mores in big-budget Hollywood filmmaking regarding cinematography, lens choices, and lighting design, how one feels about how “Wicked” looks is, of course, up to them.

What’s worth pointing out when comparing “Wicked” to “The Phantom Menace,” “Attack of the Clones,” and “Revenge of the Sith” is that, in the case of all four films, their gaudy, slick, almost off-puttingly garish aesthetic is the choice of their respective directors. For Lucas and “Star Wars,” the visual approach was undertaken for reasons involving the director’s interest in using the films to push the envelope of emerging technology (“Revenge of the Sith” was one of the first major Hollywood releases to be offered in digital projection, a format that’s now industry standard). For Chu and “Wicked,” the choice seems to be about emulating the look of Victor Fleming’s “Wizard of Oz” while using modern techniques, in addition to keeping the film looking like Oz is “a real place,” according to Chu. That approach, making a fantasy world realistic, is something on par with other fantasy movies made in the last several years.

For both “Wicked” and the Prequels, I’d argue there’s a secret third reason for this, however. Both films involve stories about faraway, magic-filled lands that are slowly but surely corrupted by the people in control of them. They’re essentially dark fairy tales, with their cheerful, colorful exterior masking the rot that emerges from within. What better way to demonstrate such contrast than making it as explicit as each film’s garish palette?

Elphaba and Glinda mirror Anakin and Obi-Wan’s relationship

At their core, the “Star Wars” prequels and “Wicked” share the same creative jumping-off point: taking two of the most iconic screen villains in movie history and making them the protagonists. Interestingly, though, while the Prequels chronicle the events and causes for what turned Anakin Skywalker (Jake Lloyd in “Phantom,” and Hayden Christensen in the latter two films) into Darth Vader, “Wicked” details the circumstances of how Elphaba came to be essentially framed as, not necessarily transformed into, the Wicked Witch. Despite that distinction, both of what makes these characters’ arcs turn involves their relationships with their closest friends: Obi-Wan Kenobi (Ewan McGregor) and Glinda aka Galinda (Ariana Grande-Butera), respectively. Specifically, both couples experience a path that takes them from rivals, to friends, to enemies.

Both Anakin and Obi-Wan and Elphaba and Galinda enjoy an extended period of rivalry at the onset of their relationships. Obi-Wan is essentially replaced as Padawan by his Master Qui-Gon Jinn (Liam Neeson) choosing to train Anakin when they find him as a young boy, and after Obi-Wan agrees to honor Qui-Gon’s wishes to train Anakin himself when he dies, the two men have a contentious rivalry that is only stopped from becoming bitter thanks to the underlying respect they have for each other. In Elphaba’s case, she is handpicked by Madame Morrible (Michelle Yeoh) for sorcery training over Galinda, drawing the girl’s ire, which makes her a target for Galinda’s mean girl-like clique during their time at Shiz University. Worse, the two are forced into being roommates, the setup bringing with it all those attendant petty living situation grievances as well.

Yet the rivals eventually turn into friends: Obi-Wan and Anakin become heroes of the Clone Wars, while Elphaba insists that Galinda be involved in magic training, which inspires Galinda to treat Elphaba better. If, in effect, these friendships become something close to a sibling or soulmate relationship, each is corrupted thanks to the machinations of a malevolent father figure: Senator Palpatine/Darth Sidious (Ian McDiarmid) and the Wizard of Oz (Jeff Goldblum), respectively. Their corrupt grasp for power and the manipulation they employ draw a wedge between the friends, leaving each member of both couples going down a path that the other cannot follow.

‘Wicked’ does for ‘The Wizard of Oz’ what the Prequels do for the Original Trilogy

“The Wizard of Oz” is a pretty uncomplicated film, at least in terms of its morality. The Wicked Witch is evil, Dorothy and her friends are good, good conquers evil, and so on. The same goes for “Star Wars,” as Darth Vader and the Empire are using the Death Star to blow up innocent planets and such, Luke and his friends are good, they blow up the Death Star, The end. While the two sequels to “Star Wars” added their own shadings of complexity to the proceedings (namely the blood relation of Luke and Leia to Vader), the notion of the Rebel Alliance and the Jedi being righteous and the Empire being evil stayed intact.

The Prequels and “Wicked” both seek to reexamine such assumptions with their stories and just as they elevate the villains of the originals to protagonists, they flip the morality that was initially assumed. Sure, the main villains of the Prequels are still ostensibly the villains seen in the Original Trilogy, yet they go to great pains to point out just how easily a supposed progressive government can be manipulated and taken over from within. Not to mention the fact that the Jedi, whose rigorous dogma and code are a point of pride and tradition, only serves to contribute to their naiveté, pushing Anakin further toward Palpatine while blinding them to his plans.

In “Wicked,” the assumed goodness of the Wizard and his edicts is what’s allowing the realm’s society to hold together. Apparently, things are fragile enough that the Wizard believes if the land’s animal population aren’t made into scapegoats, everything could fall into chaos. As he and Morrible attempt to turn Elphaba into essentially a tool of the state, their plan backfires, and they pivot by making Elphaba into a Wicked Witch figure that they can hang their propaganda and fear onto.

The function of the Prequel Trilogy and “Wicked,” then, is to make audiences take another more sober, more mature look at their myths and fairy tales. They’re big, splashy, gaudy, often goofy films that carry with them an underpinning of critique and new context. As Glinda mentions at the beginning of “Wicked,” people have to be told the whole, true story before any judgment can be rendered. “Revenge of the Sith” ended with a thrilling yet heartbreaking lightsaber duel between Anakin and Obi-Wan; might we be in for a Glinda/Elphaba magic duel in “Wicked: Part Two?” I’ll have “Battle of the Heroes” cued up just in case.

“Wicked” is now playing in theaters everywhere.