The evolution of design from crafting into liberal art of technology

First, we need to understand why design problems seem to become increasingly complex day by day. I get inspiration from Richard Buchanan (1992) for the term “design as a new liberal art of technological culture”. In the traditional sense, liberal art means a revolutionary transformation. Design began with fulfilling functional needs such as creating an artifact, painting, or propaganda poster (Buchanan, 1992). As society and culture evolved, so did design, it became a segmented profession, gaining exposure from technical and research knowledge, becoming a liberal art of technology. This means that design, as a creative skill, engages with technology, social culture, and human values, emphasizing the importance of design in shaping how we interact with technology and the environment.

Therefore, the fact that design roles are shaping society does not merely focus on aesthetics but also requires the ability to think holistically and integrate various knowledge areas. Design forms both an art and a science of putting things together. One of the main challenges designers face, impacted by this evolution, is to enhance their individual abilities to see the big picture from the social variables while also shifting to the details to connect patterns and comfortably staying in uncertainty to understand a wicked situation.

Design problem as a complex problem

Can you imagine facing environmental issues such as food waste or wildfire? If these problems are too vague, consider the challenges when a brand designer needs to expand their product to a completely new and different target market, or an UX designer needs to create a persuasive design to increase product sales.

Isn’t it complex when they need to consider the cultural context of society, face fluctuating requirements, explore solutions while considering tight budgets, and connect psychological theory with hopes that their hypothesis leads to a successful outcome?

“Design problem as a wicked problem — the time of many problems occur, increasing complexity, rapid changes from the environment, and involving trans-disciplinary knowledge.” — Rebecca Price (2019), In Pursuit of Design-Led Transition.

Design problems have transformed into complex, wicked problems, or maybe they always were before we realized it — articulated as conditions that lack clarity and definitive solutions, meaning there is no stopping rule that says the problem has been “solved.” Instead, it is necessary to continuously rethink and adapt to updated conditions. Designers need to navigate these conditions themselves, applying an iterative process, which makes exploration not as easy as it seems, it can lead to feelings of frustration, overwhelm, and anxiety.

The nature of design activities can be defined as two major phases: problem definition — an analytic phase where the wicked condition is disentangled — and problem solution — a synthetic phase where designers explore potential solutions (Rittel, 1973). This concept is similar to the famous double diamond of the design process, in which the author divides the process into four phases: Discover, Design, Develop, and Deliver.

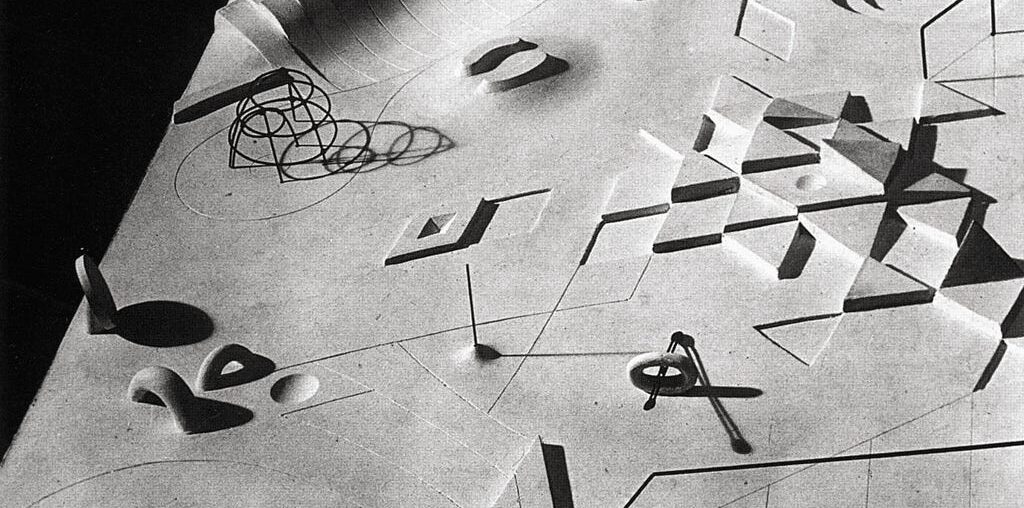

The design process continuously shifts between these phases, all iteratively while embracing ambiguity to unpack the wicked condition. Due to that condition, one crucial aspect of design activities is pattern recognition to find cross-relations. Edward de Bono, in his book Lateral Thinking, talks about establishing code communication as a mind language that can create a symbolic system that allows for understanding complex concepts in a simpler way. The designer’s task is to establish their own code of communication to help unpack wicked problems, seek patterns, and connect them with different variables. This system acts like a self-established framework that helps designers make sense of disparate information.

The play and playfulness

We understand play as an activity that produces pleasure and fun. Johan Huizinga (1949), the Dutch philosopher and author of Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture, defined play as a cultural phenomenon that is older than culture itself. It is something natural that humans do without needing to learn it. In practice, play goes beyond just physical activity; it evokes feelings of joy, tension, and satisfaction. Interestingly, play doesn’t necessarily have to be fun — it is pleasurable, which can come from serious or even dangerous activities (Sicart, 2014). In the six key principles of play, Huizinga mentioned that play needs to be temporary with specific approved rules, meaning players need to pretend in a created temporary sphere and within a limited time to complete defined goals. The goals need to be believed by everyone, such as the score in football — a translation of putting the ball into the opponent’s goal. Even the goals can be more abstract, like role-playing games with a purpose to explore different identities and understand different perspectives; players need to pretend to be someone else in a different context, which also enhances the ability to imagine different conditions.