Database queries are a pretty surprisingly powerful tool that can solve seemingly intractable problems.

It is a fun coding challenge to do things in SQL. I’ve seen people solve sudokus or do advent of code, or you can build a datalog on SQL with a little metaprogramming (maybe even fully internally). It is also possible to build a CHR (constraint handling rules) system on SQL or a graph rewriting system on SQL. Here I talk about how one can use SQL queries to do graph instruction matching https://www.philipzucker.com/imatch-datalog/ .

SQL is a feature rich language, it is not surprising that you can do these things from that perspective, using this and that odd feature. But even the simple idealized “SELECT FROM WHERE” core of SQL has a lot of power.

From a logical perspective, this core is basically conjunctive queries https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conjunctive_query#Relationship_to_other_query_languages . Each table is a logical predicate, each variable is bound to a row of a column. The SELECT fields are bits that aren’t being existentially bound and therefore hidden, aka free variables.

$\exists y. edge(x,y) \land path(y,z)$ is the predicate form of the query SELECT edge.a, path.b from edge, path WHERE edge.b = path.a. There is a little bit of rearrangement from the entry centric view of predicates to the row centric view of SQL. I am not aware of a way to easily give a name to a particular entry in sql. I used this correspondence to describe how to either build a datalog engine on sql, or hand compile your datalog rules to sql https://www.philipzucker.com/tiny-sqlite-datalog/ .

From a more imperative perspective, SELECT-FROM-WHERE statements are basically for loops. SQL is an odd language in that the FROM comes after the SELECT. This puts a row variables binding site after their usage points. Maybe this isn’t that crazy considering set comprehension {x for x in A if x > 0} is quite similar.

| SQL | Python |

FROM mytable as row_a |

for row_a in mytable: |

WHERE row_a.col1 = rowa.col2 |

if row_a.col1 == row_a.col2: |

SELECT row_a.col1, row_a.col2 |

yield row_a.col1, row_a.col2 |

A thing SQL engines do is that they rearrange and optimize these loops and refactor them into joins and other things. Python for loops however execute just like you say it (slowly).

Search problems over finite spaces can be solved by brute force loops. Enumerate all possibilities and take the ones that work.

So in this manner SQL is a constraint solver.

An example constraint satisfaction puzzle is the send more money puzzle https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Verbal_arithmetic in which we need to find digits S,E,N,D,M,O,R,Y such that SEND + MORE = MONEY.

A pure python version of the send more money puzzle with simplistic pruning is

def solve_send_money():

for s in range(1, 10): # S must be non-zero

for e in range(10):

if e == s:

continue

for n in range(10):

if n in (s, e):

continue

for d in range(10):

if d in (s, e, n):

continue

for m in range(1, 10): # M must be non-zero

if m in (s, e, n, d):

continue

for o in range(10):

if o in (s, e, n, d, m):

continue

for r in range(10):

if r in (s, e, n, d, m, o):

continue

for y in range(10):

if y in (s, e, n, d, m, o, r):

continue

# Convert SEND, MORE, and MONEY to integers

send = 1000 * s + 100 * e + 10 * n + d

more = 1000 * m + 100 * o + 10 * r + e

money = 10000 * m + 1000 * o + 100 * n + 10 * e + y

if send + more == money:

return (s,e,n,d,m,o,r,e,m,o,n,e,y), send, more, money

%%timeit

solve_send_money()

762 ms ± 35 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 1 loop each)

SQL Send More Money

We can write the same thing in SQL and execute using duckdb or sqlite. Duckdb is a bit faster and is faster than the pure python version.

import sqlite3

import duckdb

query = """

WITH RECURSIVE digits(digit) AS (

SELECT 0

UNION ALL

SELECT digit + 1

FROM digits

WHERE digit < 9

)

SELECT s.digit AS S, e.digit AS E, n.digit AS N, d.digit AS D,

m.digit AS M, o.digit AS O, r.digit AS R, y.digit AS Y

FROM digits s, digits e, digits n, digits d, digits m, digits o, digits r, digits y

WHERE s.digit <> e.digit AND s.digit <> n.digit AND s.digit <> d.digit AND s.digit <> m.digit AND

s.digit <> o.digit AND s.digit <> r.digit AND s.digit <> y.digit AND

e.digit <> n.digit AND e.digit <> d.digit AND e.digit <> m.digit AND

e.digit <> o.digit AND e.digit <> r.digit AND e.digit <> y.digit AND

n.digit <> d.digit AND n.digit <> m.digit AND n.digit <> o.digit AND

n.digit <> r.digit AND n.digit <> y.digit AND

d.digit <> m.digit AND d.digit <> o.digit AND d.digit <> r.digit AND

d.digit <> y.digit AND

m.digit <> o.digit AND m.digit <> r.digit AND m.digit <> y.digit AND

o.digit <> r.digit AND o.digit <> y.digit AND

r.digit <> y.digit AND

s.digit <> 0 AND m.digit <> 0 AND

(1000 * s.digit + 100 * e.digit + 10 * n.digit + d.digit) +

(1000 * m.digit + 100 * o.digit + 10 * r.digit + e.digit) =

(10000 * m.digit + 1000 * o.digit + 100 * n.digit + 10 * e.digit + y.digit);

"""

conn = sqlite3.connect(":memory:")

conn.execute(query).fetchall()

[(9, 5, 6, 7, 1, 0, 8, 2)]

%%timeit

conn = sqlite3.connect(":memory:")

conn.execute(query).fetchone()

969 ms ± 74.5 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 1 loop each)

%%timeit

conn = duckdb.connect() # not really a noticeable part of benchmark

conn.execute(query).fetchone()

240 ms ± 16.7 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 1 loop each)

Bonus: C Send More Money

This does raise the question of comparing to a C version. Quite a bit faster indeed.

%%file /tmp/money.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <time.h>

int main() {

clock_t start_time = clock();

//int niter = 0; Adding this slows clang down quite a bit

for (int s = 1; s < 10; s++) { // S must be non-zero

for (int e = 0; e < 10; e++) {

if (e == s) continue;

for (int n = 0; n < 10; n++) {

if (n == s || n == e) continue;

for (int d = 0; d < 10; d++) {

if (d == s || d == e || d == n) continue;

for (int m = 1; m < 10; m++) { // M must be non-zero

if (m == s || m == e || m == n || m == d) continue;

for (int o = 0; o < 10; o++) {

if (o == s || o == e || o == n || o == d || o == m) continue;

for (int r = 0; r < 10; r++) {

if (r == s || r == e || r == n || r == d || r == m || r == o) continue;

for (int y = 0; y < 10; y++) {

if (y == s || y == e || y == n || y == d || y == m || y == o || y == r) continue;

// Calculate SEND, MORE, and MONEY

int send = 1000 * s + 100 * e + 10 * n + d;

int more = 1000 * m + 100 * o + 10 * r + e;

int money = 10000 * m + 1000 * o + 100 * n + 10 * e + y;

//niter++;

if (send + more == money) {

clock_t end_time = clock();

double time_taken = ((double)(end_time - start_time)) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC;

printf("Time taken by loops: %.6f seconds\n", time_taken);

printf("SEND = %d, MORE = %d, MONEY = %d\n", send, more, money);

//printf("Tests: %d\n", niter);

return 0;

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

return 1;

}

! clang -O3 -march=native -o /tmp/money /tmp/money.c && /tmp/money

Time taken by loops: 0.003991 seconds

SEND = 9567, MORE = 1085, MONEY = 10652

! gcc -O3 -march=native -o /tmp/money /tmp/money.c && /tmp/money

Time taken by loops: 0.019185 seconds

SEND = 9567, MORE = 1085, MONEY = 10652

Hmm. My system clang vs gcc is another 5x? That’s kind of surprising. I have a new clang (20) and an old gcc 11.4. Maybe that’s enough. The thing also that it may be rearranging the loops? If I try to add a counter, clang slows down to about gcc. Very interesting.

There is another perspective on what SQL is doing. It is finding a mapping (a homomorphism) between the query and the database.

We have intuition about databases that comes from typically thinking about small queries (< 100 tables reference in FROM statements) and big databases (millions, billions or more of rows).

The running time of naive nested loops is exponential in the number of loops. Considered as a function of the size the of query, database queries are quite computationally expensive.

I have heard that I should be scared of subgraph matching or graph isomorphism because they are NP ish. But in many common cases, the size of the patterns is pretty small, and the size of the database is pretty big. So the problem is not that hard.

Graphs can be easily mapped into database tables as an edge table with two columns.

Here for example I can turn a networkx graph into a sqlite table

import sqlite3

import networkx as nx

def db_of_graph(conn, G):

con.executemany("INSERT INTO nodes VALUES (?)", map(lambda v : (v,), G.nodes))

con.executemany("INSERT INTO edges VALUES (?, ?)", G.edges)

if not G.is_directed():

con.executemany("INSERT INTO edges VALUES (?, ?)", [(j,i) for i,j in G.edges])

And conversely export the edge table back out into a networkx graph.

def graph_of_db(con):

G = nx.DiGraph()

res = con.execute("SELECT * FROM nodes")

G.add_nodes_from(map(lambda x: x[0], res.fetchall()))

res = con.execute("SELECT * FROM edges")

G.add_edges_from(res.fetchall())

return G

The form of these simple FROM-SELECT-WHERE queries (conjuctive queries) is remarkably similar to a database itself, but with symbolic entries. Each FROM would become a row in this symbolic database. We can for example convert a graph also into a query that will find the image of the graph in the database. The solutions to this query are graph homomorphisms. When codegenning SQL I find maintaining separate select from where lists to be a useful thing.

def query_of_graph(G,unique=False):

"""Unique will give subgraph isomorphism"""

selects = []

froms = []

wheres = []

for node in G:

froms += [f"nodes AS v{node}"]

selects += [f"v{node}.v AS v{node}"]

for i, (a,b) in enumerate(G.edges):

froms += [f"edges as e{i}"]

wheres += [f"e{i}.src = v{a}.v" , f"e{i}.dst = v{b}.v"]

if unique:

for node in G:

for node2 in G:

if node != node2:

wheres += [f"v{node} != v{node2}"]

sql = "SELECT " + ", ".join(selects) + \

"\nFROM " + ", ".join(froms) + \

"\nWHERE " + " AND ".join(wheres)

return sql

def clear_db(con):

con.execute("DELETE FROM nodes")

con.execute("DELETE FROM edges")

con = sqlite3.connect(":memory:")

con.execute("CREATE TABLE nodes(v)")

con.execute("CREATE TABLE edges(src,dst)")

<sqlite3.Cursor at 0x7b99507714c0>

Some Examples

We can make a graph and insert the appropriate edge table into the database.

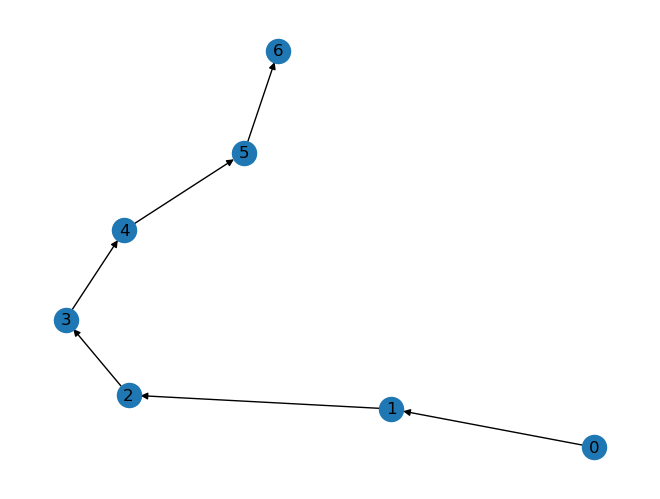

G = nx.path_graph(7, create_using=nx.DiGraph)

nx.draw(G, with_labels=True)

db_of_graph(con, G)

con.execute("SELECT * from edges").fetchall()

[(0, 1), (1, 2), (2, 3), (3, 4), (4, 5), (5, 6)]

We can seek out the smaller pattern graph from the larger graph

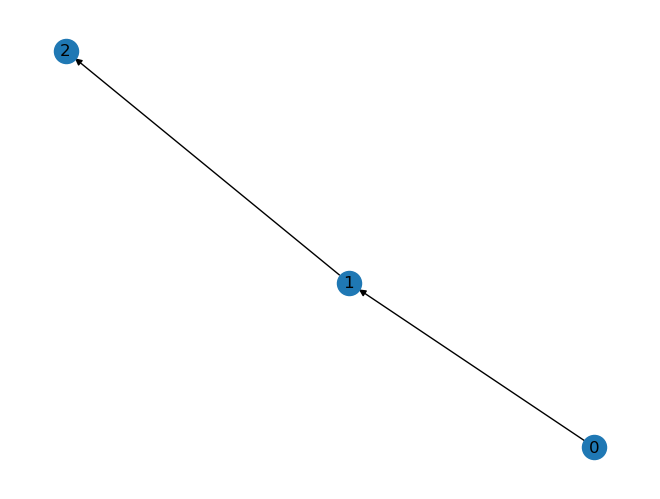

lhs = nx.path_graph(3, create_using=nx.DiGraph)

nx.draw(lhs, with_labels=True)

print(query_of_graph(lhs))

SELECT v0.v AS v0, v1.v AS v1, v2.v AS v2

FROM nodes AS v0, nodes AS v1, nodes AS v2, edges as e0, edges as e1

WHERE e0.src = v0.v AND e0.dst = v1.v AND e1.src = v1.v AND e1.dst = v2.v

con.execute(query_of_graph(lhs)).fetchall()

[(0, 1, 2), (1, 2, 3), (2, 3, 4), (3, 4, 5), (4, 5, 6)]

Automorphisms

We can also find all homomorphisms of the graph into itself, of which there is only one for the directed graph.

con.execute(query_of_graph(G)).fetchall()

For the undirected graph, there are more homomorphisms.

clear_db(con)

G = nx.path_graph(4) # undirected

db_of_graph(con, G)

res = con.execute(query_of_graph(G))

res.fetchall()

[(1, 0, 1, 0),

(1, 0, 1, 2),

(0, 1, 0, 1),

(0, 1, 2, 1),

(0, 1, 2, 3),

(2, 1, 0, 1),

(2, 1, 2, 1),

(2, 1, 2, 3),

(1, 2, 1, 0),

(1, 2, 1, 2),

(1, 2, 3, 2),

(3, 2, 1, 0),

(3, 2, 1, 2),

(3, 2, 3, 2),

(2, 3, 2, 1),

(2, 3, 2, 3)]

A homomorphism into yourself is not an isomorphism. You need a uniqueness constraint also for that, which can easily be expressed in SQL. The undirected path graph has 2 automorphisms, the identity and the reversal.

res = con.execute(query_of_graph(G,unique=True))

res.fetchall()

[(0, 1, 2, 3), (3, 2, 1, 0)]

Graph Coloring

We can also implement a coloring as an homomorphism into the fully connected graph, representing the colors and allowed edges between colors.

clear_db(con)

colors = nx.complete_graph(2) # a two coloring graph

db_of_graph(con,colors)

res = con.execute("SELECT * FROM edges")

res = print(res.fetchall())

res = con.execute(query_of_graph(G)) # two dimer colorings

print(res.fetchall())

[(1, 0, 1, 0), (0, 1, 0, 1)]

https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/335168.335209 Constraint Satisfaction and Database Theory: a Tutorial Moshe Y. Vardi

https://users.soe.ucsc.edu/~kolaitis/talks/csp-oxford.pdf Constraint Satisfaction and Logic Phokion G. Kolaitis

https://berkeley-cs294-248.github.io/ CS294-248: Topics in Database Theory

Alice book http://webdam.inria.fr/Alice/ Foundations of Databases. I know there is some discussion of query containment involvinf something like a “symbolic” database corresponding to a query.

Have you tried rubbing a database on it? https://www.hytradboi.com/ Databases used for sometimes unusual purposes

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mykR7mP5Zdk&t=269s&ab_channel=SimonsInstitute Logic and Databases Phokion Kolaitis

https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3018882.3018893 Language-integrated query with ordering, grouping and outer joins https://okmij.org/ftp/meta-programming/index.html#SQUR

It is also noted that moanadic comprehension can do sql stuf https://ncatlab.org/nlab/files/WadlerMonads.pdf https://ghc.gitlab.haskell.org/ghc/doc/users_guide/exts/monad_comprehensions.html https://ghc.gitlab.haskell.org/ghc/doc/users_guide/exts/generalised_list_comprehensions.html#generalised-list-comprehensions https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2034675.2034678

LINQ is a whole thing

Query containment. Since you can make a sql query to find homomorphisms, you can check query containment as a sql query itself. Isn’t that fun?

The symbolic database as a herbrand model.

Gra

I’ve never seriously used a graph database, but I kind of can’t see the appeal for this reason. I find pretty often modelling domains as graphs to not actually map that well because I want a notion of ordering.

I really had this one rotting in my draft backlog for a long time. Good to just dump stuff out.

SQL is a model checker for first order logic. SQL + something like NOT and EXISTS statements can express any first order logic statement.

Model checking has a connotation of being about temporal logic, or software system checking. But the term itself is talking about literally checking a model satisfies a formula M |= t. Model checking is a general concept that can be applied to any logic with a notion of smenantics.

Model checking is also kind of saying there is a kind of homomorphism between the syntax and semantics.

This is also a confusion that we have in talking about the “complexity” of a logic. The ocmplexity depends on which question we are asking. Are me asking satisfiability or model checking? Satisfiiability is also aasking about the M |= t models question, but it is of the form formula -> option model rather than the form model -> formula -> bool. The moding of the question is different.

When people talk about SAT being NP, they are talking about the satisfiability problem.

When they talk about existential second order logic being NP, they are talking about the model checking problem https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fagin%27s_theorem https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Descriptive_complexity_theory

When people talk about datalog being PSPACE co

Tree decomposition for dynamic programming

CSP

SQL queries are enumerating homomorphisms between the query and the database. This perspective puts the query and the database on smilar footing, which feels odd.

As a subcase of this capability, if the database is holding an edge table and attributes, then a query is a graph homomorphism solver.

If we dymmetrically place two graphs into the database and in a query, we can enumerate isomoprhisms. Isn’t that fun?

Another perspective is that the query is a formula, and the database is a model of the formula.

We are used to small queries and large databases, but this is not a definition

A perspective on what a constraint satisfaction problem is is that is is a homomorphism problem.

For example, graph coloring is a homomorphism from a graph to a complete graph of colors (with no self edges).

Constraint satisfaction is an assignment to variables values frm their domain subject to constraints. The particular connectivty of a problem can be represented by a hypergraph. The target structure represents the domains the variables can take on, and the constraint hyperedges map to a relation representing the constraint.

A class of CSP problems is allowing the connecvtivity graph to vary, while keeping the target (the types of constraints fixed). Is this a useful characterization? Eh. It’s interesting that it ties into other mathemtical topicas.

The naive solution of a constraint satsifaction problem is to just make a big sequence of loops, pruning / breaking with checks that constraint are satisifed. We want to push the checks as high as possible.

This a a very static perspective.

More dynammically, we want to pick the variable ordering inside the choice branches. This is more of a backtracking feel. We do proppagation to disallow subchoices

A problem that is easy to embed into database queries is graph homomomorphism. Queries and databases feel very different, but they are more symettric than you might think.

In typical usage, queries are small and databases are large.

A graph coloring problem can be mdelled as fnding a graph homomorphism into a complete graph. This flips the intuition on it’s head with a large query and small database. Examples like these are better served probably by a constraint satisfaction solver or SAT style techniques.

The middle ground of roughly equal graphs is a graph isomorphism problem. Custom solvers like nauty exist for this case too.

import sqlite3

import networkx as nx

def db_of_graph(conn, G):

con.executemany("INSERT INTO nodes VALUES (?)", map(lambda v : (v,), G.nodes))

con.executemany("INSERT INTO edges VALUES (?, ?)", G.edges)

def graph_of_db(con):

G = nx.DiGraph()

res = con.execute("SELECT * FROM nodes")

G.add_nodes_from(map(lambda x: x[0], res.fetchall()))

res = con.execute("SELECT * FROM edges")

G.add_edges_from(res.fetchall())

return G

def query_of_graph(G):

selects = []

froms = []

wheres = []

for node in G:

froms += [f"nodes AS v{node}"]

selects += [f"v{node}.v AS v{node}"]

for i, (a,b) in enumerate(G.edges):

froms += [f"edges as e{i}"]

wheres += [f"e{i}.src = v{a}.v" , f"e{i}.dst = v{b}.v"]

sql = "SELECT " + ", ".join(selects) + \

"\nFROM " + ", ".join(froms) + \

"\nWHERE " + " AND ".join(wheres)

return sql

G = nx.path_graph(7, create_using=nx.DiGraph)

lhs = nx.path_graph(3, create_using=nx.DiGraph)

con = sqlite3.connect(":memory:")

con.execute("CREATE TABLE nodes(v)")

con.execute("CREATE TABLE edges(src,dst)")

db_of_graph(con, G)

res = con.execute(query_of_graph(lhs))

print(res.fetchall())

# Result: [(0, 1, 2), (1, 2, 3), (2, 3, 4), (3, 4, 5), (4, 5, 6)]

print(graph_of_db(con))

"DELETE FROM nodes WHERE nodes.v = ?"

"DELETE FROM edges where edges.src = ? OR edges.dst = ?"

con.execute("DELETE FROM nodes")

con.execute("DELETE FROM edges")

colors = nx.complete_graph(2) # a two coloring

db_of_graph(con,colors)

# symmetrize. Maybe db_of_graph should do this. if not isinstanc(G,nx.DiGraph)

con.execute("INSERT INTO edges SELECT edges.dst, edges.src FROM edges")

res = con.execute("SELECT * FROM edges")

res = print(res.fetchall())

res = con.execute(query_of_graph(G))

print(res.fetchall())

# [(1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1), (0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0)]

Graph coloring can be solved through dynamic programming. If we cut up a graph, we only need to know if it can be colored with particular choices at interfaces. Choosing interfaces like this is a graph partitioning problem, but also is a tree decomposition.

One of the things that I found appealing about category theory is that it presents a design methodology to convert things that look graph-like like string diagrams into term-like expresssions of combinators.

Hmm. python-metis is not a thing anymore? Just pip install metis, it works with networkx anyway

import metis

import networkx as nx

G = nx.path_graph(7)

edgecuts, parts = metis.part_graph(G,3)

print(edgecuts, parts)

print(nx.community.kernighan_lin_bisection(G)) # anneal a cut by node swapping

print(list(nx.community.girvan_newman(G))) # remove edges from graph

Recursively partition to build query plan (?)

You can build a query plan using these graph partitioners

but also query planners can be used to find partitions / tree decompositions.

There are also custom solvers for this.

graph datastructure

[(v1,v2)]

Node(outs,ins)

= [(outs,ins)]

out, inner , in

dynamic tree decomposition

hyprgraph data structure